‘Bugger Bognor’: the incredible history of famous last words

I’ve long been interested in people’s last words – seeking inspiration for my own. Why was this town on England’s south coast the focus of King George V’s dying breath?

By bouncing up in the blue in Boeings I’ve been blessed to have visited many places starting with B. Brisbane, Budapest, Beijing, Boston and Berlin come to mind. But not the B on my bucket list. Bognor. Or to use its full name, Bognor Regis.

I’ve long wanted to know why King George V so detested Bognor that he made it the focus of his dying breath. He’d been sent to the town on England’s south coast in the hope that the sea breezes would help his health. But Bognor’s main claim to fame became the king’s reputed exhortation, “Bugger Bognor.” Hence its place in history – and the history of last words.

I’ve long been interested in people’s last words – seeking inspiration for my own, destined to be delivered in the not-too-distant future.

“Forgive them Father, for they know not what they do” is a prime example, although Jesus uniquely returned for seconds.

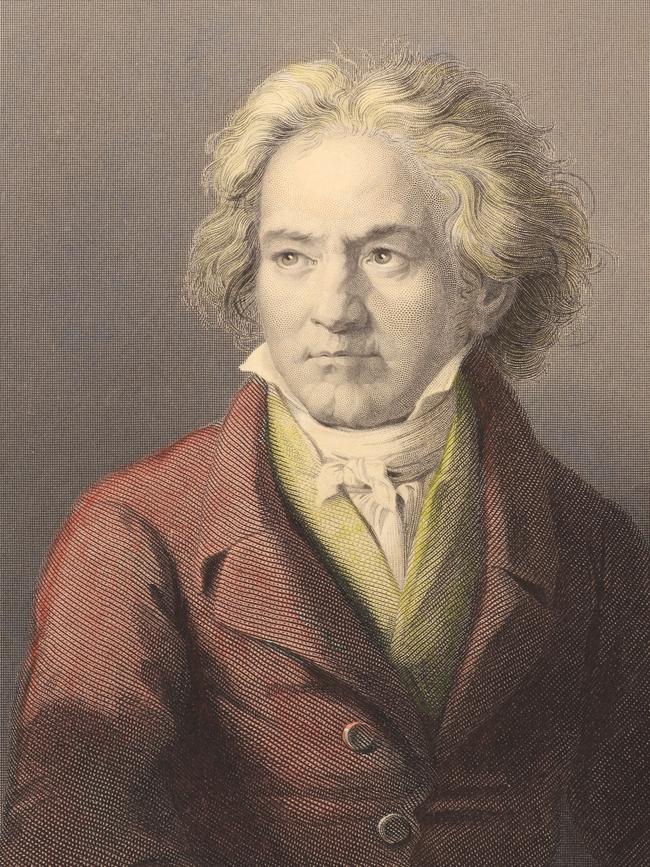

“Friends applaud, the comedy is over” provided the curtain call for Beethoven.

No “fight the dying of the light” for that old curmudgeon Winston Churchill, whose exit line was “Oh, I am so bored with it all!”

According to Shakespeare, “Et tu Brute? Then fall, Caesar!” was the choice of another popular political leader, and we’ve a wide variety of last words from kings and queens, both in fiction and in fact. Like “A horse! A horse! My kingdom for as horse!” from the Bard’s Richard III, and “All my possessions for a moment of time!” from the actual Elizabeth I. That certainly betters “Bugger Bognor.”

Other au revoirs from royals must include Anne Boleyn’s long oration on the block. It ended thus, after the poor woman had been blindfolded. “To Jesus Christ I commend my soul, Lord Jesu receive my soul.” Some years later Charles I, in similar heady (and soon to be headless) circumstances said, “I go from a corruptible to an incorruptible Crown, where no disturbance can be.”

The old bolshie Karl Marx was contemptuous of the terminal tradition. “Go on, get out! Last words are for fools who haven’t said enough!”

Bing Crosby? “That was a great game of golf.” Anna Pavlova? “Get my Swan costume ready.” And a particular favourite came from a fellow theatrical in the sainted Oscar Wilde. Witty to the end, Oscar complained: “My wallpaper and I are fighting a duel to the death. One of us has got to go.”

When asked to finally renounce the Devil, French writer Voltaire said: “This is not the time to be making new enemies.”

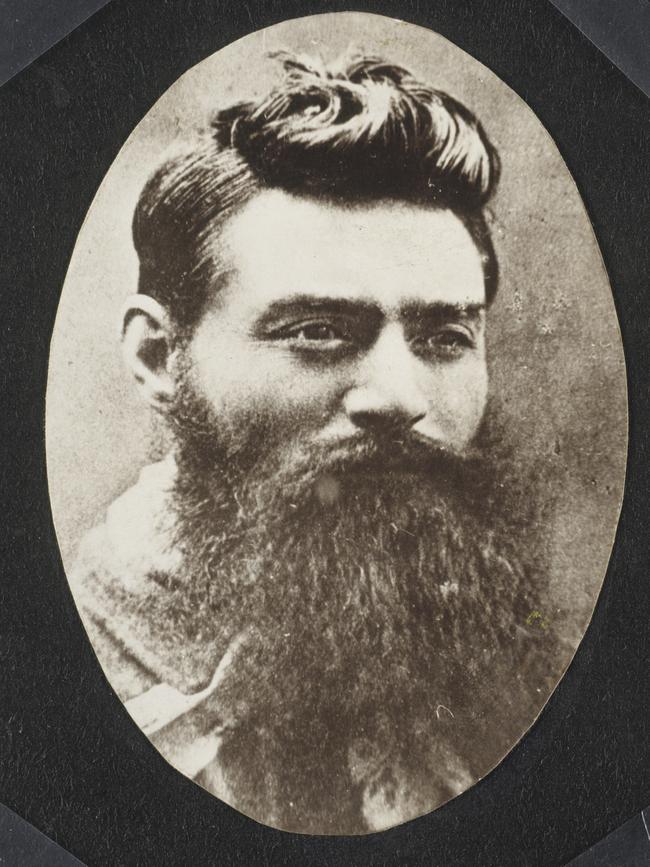

But the greatest last words of all time come from closer in time and place. On November 11, 1880. Yes, November 11, the same date Gough Whitlam would be executed by Governor General John Kerr AK GCMG GCVO QC. On the same date World War I officially ended.

Three words spoken from the gallows with a noose around the speaker’s neck. The neck of Edward “Ned” Kelly. Hanged in the Old Melbourne Gaol on theorders of Judge Redmond Barry KCMG.

Though some pedants dispute this ultimate utterance, I choose to believe in it wholeheartedly – because of its simplicity, its profundity, its poetry, its irony. It is the last word in last words.

“Such is life.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout