Blood, milk and coke: Sydney milkman sent to kill Pablo Escobar

How did a Sydney milkman end up in a hit squad sent to kill drug lord Pablo Escobar?

She keeps the briefcase in the linen cupboard, high up on the top shelf, resting on the towels and bed sheets she uses the least. The briefcase is tan coloured and old and made of pig and snake skin. Felicity O’Neill places it on her dining table and wears a nervous smile as her thumbs compress the gold locks on either side of the leather handle. Inside the briefcase is the story of her former soulmate, Terry Tangney, told through neatly handwritten letters from Africa and South America and Afghanistan, grainy photographs and dot-point military diaries — the untold and extraordinary tale of how a nervy and unheroic milkman from Sydney’s Cabramatta joined a 12-man mercenary hit squad on a globe-crossing covert mission to assassinate Pablo Escobar, Colombia’s “King of Cocaine” who earned up to $21.9 billion a year at the late-’80s height of his bloody Medellin cartel narco-terrorist reign.

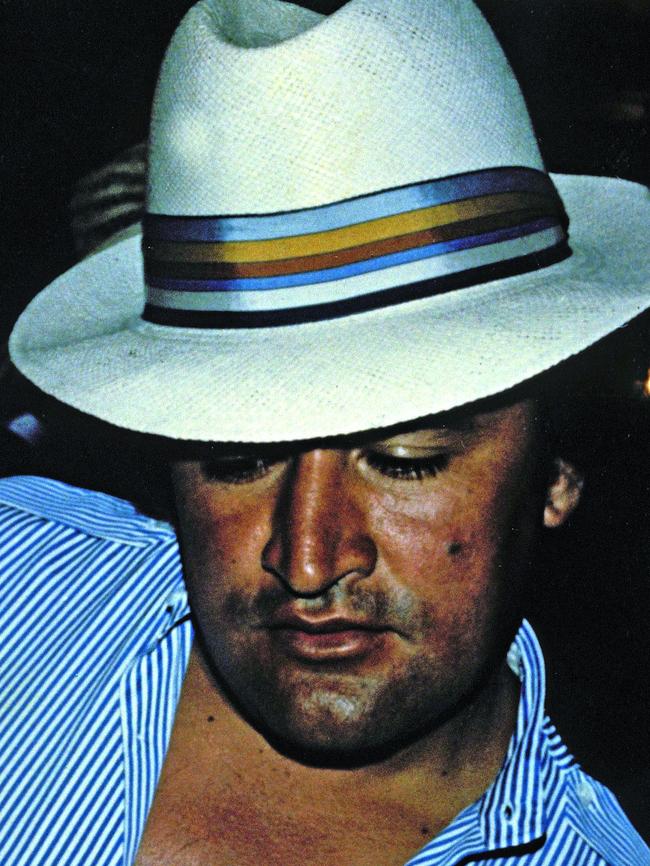

Northern Tasmania, late winter, 2016. The snow sits like icing sugar on the hills surrounding Felicity’s house, a former church. In this cosy Christmas-card setting her eyes dance across the contents of the briefcase and settle on a photo of an African guerilla lying in scrub, half his face blown off. She finds medals for her ex-husband’s mercenary service in the Rhodesian Light Infantry and a black-and-white photo of him with a regal moustache. Another shot of Terry Tangney the mercenary serving in a secret South African unit in Angola, holding an antipersonnel mine, captioned: “The AP mine I sat on but didn’t go off.” And she finds the disk that contains the book. The book that never made it out of the briefcase. “He always said to me, ‘They never taught me how not to think about war’,” Felicity says, her bright features dimming. “This is why he used to carry on with his book so much, because he could relive every day of it. He’d isolate himself for days, just write and write. He just wanted to get that book out. It was such a passion. An obsession.”

Tangney wanted the world to see the things he saw in his head. He wanted us to know his outlandish story: how he went from the western Sydney morning milk run, just out of high school, into the Australian Army — where he served for three years from 1971, narrowly missing out on a longed-for tour of Vietnam — and on into the lucrative world of the warrior-for-hire, in search of himself, in search of respect from his World War II hero father, in search of a battlefield death bed. He wanted actor Bryan Brown to be crouching shit-scared but heroic in dense African scrub in the Terry Tangney biopic, a cinematic war epic about the larrikin Aussie milkman who prided himself on the trouble he landed in.

He wrote in a blurred and sleepless fever of post-battle drink and drugs, the fog of war and the bedroom fog of a cigar-thick reefer. There are 49 chapters, each ranging from 12,000 to 35,000 words. He called it Whores of War. It’s a book about 1980s Africa, Colombia and Ecuador and death and guns and wartime atrocities and what it feels like to watch evil men gun down innocents. It’s a book about soldiers of fortune and cocaine abuse and adrenaline addiction, an epic dog’s breakfast of a book that nobody ever read but Felicity. Because Tangney was never taught to write. He was only taught to kill.

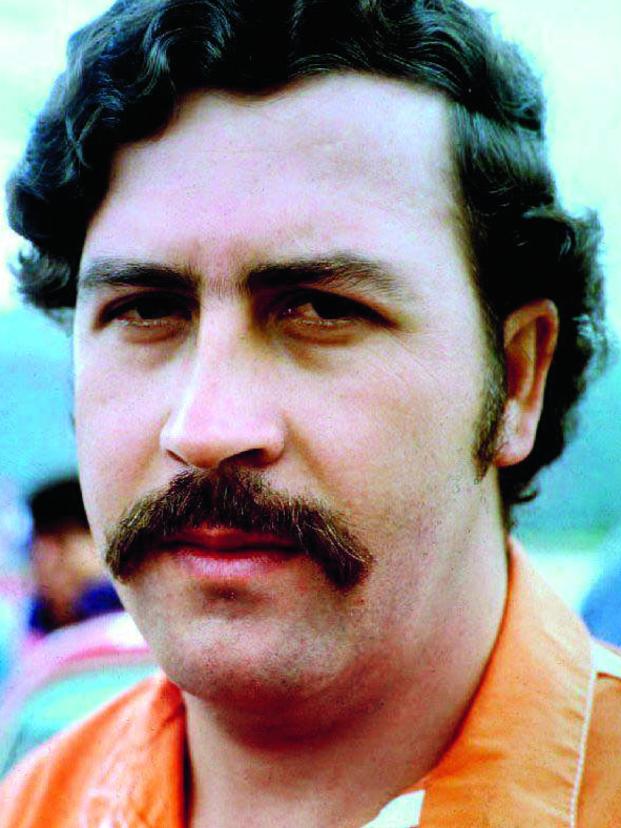

He took 36 chapters to haul his painful opus to where it should have started in the first place. Colombia, 1988, on the floating arrival jetty of Pablo Escobar’s “Fantasy Island” hide-out, a boggy jungle sanctuary on the outskirts of Bogotá, where the Cabramatta milkman begged for forgiveness and protection from a statue of the Virgin Mary, deep in the heart of the most dangerous and successful criminal organisation in modern history.

Terry Tangney stared up at that Virgin Mary statue clutching her baby Jesus and somewhere deep in his busy mind were the events surrounding his first kill, the events of Rhodesia, 1977, the fireforce helicopter assaults of the Rhodesian Light Infantry (RLI) near bush villages under the control of African nationalist guerillas where, he writes, “anything or anyone living near the battle zone became a legitimate target”. Mud huts and orange smoke canisters and machinegun madness and the adventurous milkman having bowel spasms with his first taste of battle. A battle-hardened Australian commander, Vietnam veteran Peter Binion, barking orders between sips of tea from an army water bottle. “Start taking those f. kers out! Clear by fire, 100m that direction, spread out, don’t bunch up.

Tangney wished immediately he was back in Sydney, back in class at Bonnyrigg High School where he first dreamt up this plan to see the world through a set of crosshairs like his dad before him. The mad and sweeping machinegun blasts into walls of elephant grass at unseen enemies didn’t figure in those boyhood dreams. Nor did the African village woman he found lying face-down in the dirt beyond the grass wall, her legs hacked off by gunfire. “I’ve got a wounded African civilian over here,” he shouted to his leader. “Keep f. king moving,” Binion ordered. And move he did, from Angola to Mozambique to Afghanistan, following endless trails of blood spilled for the highest bidder. His RLI chaplain once assured him that God was on the side of Tangney and his mercenary mates. A decade later, on the rickety pier of Escobar’s Fantasy Island, the Virgin Mary had no comment.

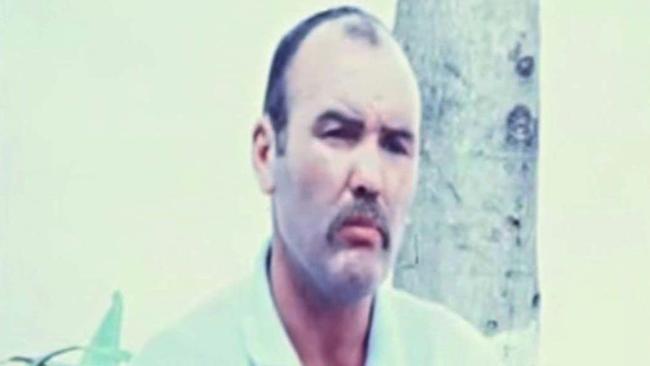

His mates were soldiers of fortune from across the globe. RLI veterans. Vietnam War veterans. Brits, Australians and South Africans mostly, all led by two British lifelong war whores, Peter McAleese and Dave Tomkins. McAleese was a Scottish-born SAS veteran with a thick moustache and little time for fools and bad shots. Tomkins — tall, blond hair, blue eyes — had been in and out of as many prison cells as he had wars.

McAleese and Tomkins built the 16-man Colombia team together. They were handsomely financed, ultimately, by Escobar, the man Tangney called “The Patron”, to spend three months in the jungles of Colombia and Ecuador training up to 100 of the cocaine cartel’s most promising gunmen — many of them teenagers; experienced murderers, inexperienced soldiers. They taught them how to load and fire rocket launchers, change a machinegun magazine, make the most of a grenade; how to construct an improvised explosive device; lay landmines for DEA agents who’d dare encroach on their jungle cocaine manufacturing laboratories. All the while, local villagers were walking past Tangney at training sessions, hauling metal drums of unprocessed liquid cocaine out of the jungle, phase one in a billion-dollar supply chain that would end on the porcelain top of a New York nightclub toilet.

They called the secret hide-out Fantasy Island because of the mansion built into the heart of it and because of the prostitutes ferried regularly from the city. But over three months, Fantasy Island came to close in on the Sydney milkman. Tropical storms, bad food, hard rain, disease. The Colombians were lazy, disorganised and arrogant; prone to random acts of violence and insanity. They viewed the US war on drugs with the same disregard they gave the jungle flies on their meal plates.

The mercenaries were visited by Escobar’s right-hand man, Jose Gonzalo Rodriguez Gacha, the sinister “El Mexicano” who had recently featured in Forbes magazine’s list of global billionaires. Gacha was impressed by the mercenary group’s methods and asked them to include his own son, Fredy Rodriguez Celades. “Young Freddy [sic], the son of ‘The Mexican’ and entourage arrived, a 20-year-old lout and overindulged slob, who had been spoilt rotten during his pampered existence,” Tangney writes. “Freddy’s first night on the island, a flash cocky young man armed with a stack of porn videos as if Fantasy Island were a holiday retreat, however, people jumped about when fat Freddy spoke.” Some days, the Colombians allowed Tangney to video their training drills in the interests of study and evaluation. Fredy Rodriguez would feature in these videos in passing glimpses. (Almost a year later, Fredy would unwittingly lead Colombian National Police and Marines to his father’s clandestine hide-out, where father and son were killed.)

Rumours spread among the mercenaries about when and where exactly this surreal assignment would end. “We agreed that there was a high probability of us receiving a bullet through the back of the head, and wind up being buried with all the other unclaimed bodies dumped at the municipal rubbish tip, to be buried under tons of garbage by massive front-end loaders,” writes Tangney. Then the mercenary group was asked to return to Bogotá and McAleese and Tomkins were summoned to the cartel’s head office on the fourth floor of an unassuming office block. While McAleese and Tomkins delicately negotiated the team’s exit out of Colombia alive, Tangney and the others were holed up in a hotel living on cocaine and Coca-Cola.

“Day 12 of captivity our ship came in,” he writes. “Tomkins and McAleese returned from the cartel’s offices, both men beaming with sheer happiness, emptying cases stuffed full of American greenbacks across the bed, the rest of our money waiting for us back in the United Kingdom to be collected at Tomkins’ English country manor.

Job done, to be sure, but their connection to Escobar would not be severed there. As Tangney was preparing to leave, a cartel man arrived at his hotel door demanding he hand over the video cassettes holding any footage he’d shot on the island. He gave them a shockproof camera case containing half a dozen tapes of random footage from his journey to Colombia. He had previously stashed the cassettes of footage from Fantasy Island in a fellow mercenary’s luggage, knowing the Colombians would come looking for them.

The mercenaries were paid about $20,000 each for three months’ work. Terry Tangney spent his money on drugs, a brand new leather jacket, a collection of emeralds and a pig and snakeskin briefcase he would carry for the rest of his life.

A message comes through from Peter McAleese with a strange number to call that should connect to an international location he won’t disclose. It doesn’t. The second number with a different international dialling code he offers won’t connect. He sends through a third number. Rule number one: keep on moving.

McAleese also wrote a book about his war whore days. It was called No Mean Soldier: The Story of the Ultimate Professional Soldier in the SAS and Other Forces. Like Tangney, he was never taught how not to be a soldier. “It’s so easy to say something bad about someone, but Terry was all right,” McAleese says down the phone line when we finally connect. “He was a steady ol’ soldier. He just moved along, did as he was told. He never shone in any way but if you wanted something done, and you told him, he always done it. Every so often he didn’t understand discipline but you get that every so often with the Aussies. Everybody loved Terry Tangney. He was one of those who got on with everyone. He was a charming guy. There was no bad in him.

But there was a complexity in Terry Tangney. He wasn’t like other mercenaries. No inherent lust for blood or gold. He openly spoke of his battlefield fears. His pre-battle bowel spasms are a puzzling theme that runs through his memoir. True courage is best shown in the face of true fear, but Tangney paints himself so openly in his book that he makes the reader wonder why on earth the suburban milkman so frequently placed himself in such dangerous situations in the first place. “We were ordinary people who got ourselves into extraordinary situations,” McAleese says. “You get the guys who like drinkin’, the guys who like thinkin’, the guys who like soldierin’. ” And every guy liked the money — often three times, four times what they’d make in a regular army.

But there was something else about Tangney. “His father had been in the army for years,” McAleese says. “He did it for his father to be sorta proud of him, you know. When he joined the army his father was over the moon. He wanted his father to be proud of him and that was it.

“He was a very sad person, actually,” Felicity O’Neill says, her small hands resting in the briefcase filled with her former husband’s mementos. “He struggled.” Felicity’s a nurse. She met Tangney in her native South Africa, where they ran a fledgling security company together for a time. “It would have been in 1989,” she says. “We were married in 1990. It was super fast. I’d never met someone like him. You couldn’t not love Terry … I didn’t find any fault in him until I was married to him.

Tangney’s book barely touches on the most compelling aspects of his life and personality. His relationship-swallowing ego. His lack of interest in any anecdote that wasn’t one of his. His inability to stay put in suburbia. His absolute adherence to Peter Binion’s command: “Keep f. king moving.

Keep moving, away from the human gore in his head, the image of that woman in the Rhodesian scrub heaving her ripped torso up across the dirt with her shaking arms. Keep moving, from daily life, from the dishes in the sink and the electricity bills on the kitchen bench. “The thing is, if you’re living on adrenaline all the time, all of a sudden, if you don’t get that fix, if you don’t have something exciting happening, you’re craving it all the time,” O’Neill says. “I think that’s why Terry needed to be with the book all the time.”

And that’s why the book was so darn long. Because he was living inside of it. The book was keeping him moving, keeping him alive. A publisher in the US wanted to see the finished product, but it was never sent. Tangney feebly claimed the cost of printing and postage wasn’t worth it.

Keep moving, from the loves of his life, from multiple wives across the world and the children he couldn’t stick around for; from the mundane nine-to-five office jobs with men who don’t bark their orders but send them in polite emails and texts with smiley faces at the bottom. Keep moving, to the world of action and adventure, the world where Pablo Escobar was still living, still counting his billions on a pool lounge in the Colombian sun, still waiting for the milkman to arrive.

“How would you like to swing the sword again, laddie?” Peter McAleese hollered down the phone line. It was early 1989. McAleese and Dave Tomkins were putting a 12-man mercenary team together for a lucrative mission, the kind a man could retire on: the assassination of Pablo Escobar. Rival drug lords from the Cali cartel had offered McAleese and Tomkins an unlimited budget to launch a helicopter assault on Escobar’s 2800ha Hacienda Napoles, 130km east of Medellin, The Patron’s sprawling holiday wonderland filled with amusement park rides and exotic animals that tourists now travel across the world to see in ruins. There would be no government interference, Tomkins was assured by his Colombian contacts. The team would be housed in luxury accommodation, given the very best military technology cocaine could buy

“Are you in or out?” McAleese asked. Tangney’s head said yes but his bowels said otherwise. “Of course I’m in, Sir,” he responded.

At a team meeting, Tomkins outlined the many risks and the many rewards, as Tangney stared into a black and white image of their target. “Also, there’s Escobar’s treasure chest that’s rumoured to contain millions of dollars that he hauls around with him everywhere he goes,” Tomkins said. “I’ve been solemnly promised by the Cali cartel that if we should find his piggy bank then the money is ours.

“In and out, thank you very much,” McAleese said. But Tangney kept staring at the photo of Escobar. “We’d been hired to slay our former employer,” he writes in the book

Arriving in Cali, Colombia, the team began collecting enough weaponry and ammo for a small army, all secretly housed in their luxury digs. Training took place in forest clearings outside of Cali. Day after day, the mercenaries forgot their fears through endless drills. Night after night, they deadened their fears in lines of coke and rounds of rum, hiding from the strict disciplinarian McAleese.

Then, in a Cali recovery sauna, Tangney had an epiphany. He went to McAleese’s bedroom suite and committed the bravest act of his life: he admitted he didn’t have the balls to be a mercenary. “He came along and said, ‘My bottle’s gone, I’ve had enough’,” says McAleese today. “I said, ‘OK, go home’. Because I didn’t want it to affect him at all. I don’t think any less of him. If he stayed around he could have been a liability.

Tangney was out. On his long multi-city hop back home he wondered why on Earth he was ever in. “I regretted not remaining in Australia where I would have remained a humble randy milkman as my only concern was irate husbands and jealous boyfriends,” he writes. “Instead, I chose this nerve-racking, ulcer-making lifestyle.

His mum and dad wept when he came home. His father walked him back into the family home in Cabramatta and down a set of stairs to a bar he’d been working on under the house. The bar was covered in photos and letters and military medals, all the keepsakes Terry had sent home during his adventures. A shrine of sorts, a tribute comprising all the mementos that would one day be stored in the briefcase atop the unused sheets of Felicity O’Neill’s linen cupboard.

It took three hours by helicopter in bad weather across heavy jungle for McAleese’s team to get within range of Escobar’s estate. But nearing their target, the lead helicopter got lost in cloud and ran out of fuel, crashing into a peak. The pilot was killed, but Tomkins and McAleese miraculously survived, left to drag their broken bodies through a reported three-day jungle escape from Escobar territory. The mission was aborted, and the drug baron stayed alive until December 1993, when he was shot through the ear after a bloody gunfight with Colombian National Police, gunned down in the streets of his beloved Medellin.

Shortly after returning from Colombia, Tangney sold his Fantasy Island videotapes to NBC for $25,000. They were packaged into a prime-time broadcast narrated by a gobsmacked seasoned American journalist: “This is the heart of cocaine country in Colombia and when these pictures were taken, this was a luxurious hide-out for the drug bosses, a place they called Fantasy Island… “The guy who was employing us, Mr Escobar, was like, wanted,” Tangney drawled to the camera. The humble milkman was asked if he was bothered by working for the cartel bosses. “I’d never really given it much thought, you know.

“Nobody will ever get rich selling stories to newspapers,” says McAleese. “I think Terry wanted to be a reporter. He fancied himself at that, you know … That’s why he had all these movies, all these films from all over the years. Terry did that and that’s probably where the fallout came between me and him.” But, he adds, “if he walked through my door today I’d be the first person to welcome him, because that’s the type of guy he was”

After losing his nerve in Colombia, Tangney tried to find it again and again. He claims the exiled king of Albania wanted to recruit him in a fight to restore his power, but Tangney’s inherent and inexplicable racism — which makes nauseating and interminable appearances throughout his book — proved too much for the royal. When Tangney heard that a group of men were seeking to launch a coup in Zaire, he flew to Belgium to pitch himself as a man who could organise it, to no avail. Between these last-ditch attempts to stave off normality, he and Felicity would continue to fly back and forth between South Africa and Australia, eventually moving to Tasmania for good in 2001.

“He was seeing a psychiatrist regularly in Tasmania,” she says. “Once, a doctor in South Africa sat me down and said, ‘Look, we’re not going to say it’s a mental illness. It’s a combination of a lot of things — it’s not just schizophrenia, it’s not just bipolar, it could be narcissism.’ I think, in a sense, Terry was quite narcissistic when he wanted to be. Then he’d be wonderful for weeks on end and we’d have the most amazing times. Then, a couple of months later, there’d be a fight every day.”

She shot him once, by accident, in their home in South Africa. Tangney had a knack of antagonising his wives to despair, walking out mid-fight in the kitchen to lie on his side of the bed, pouring an ashtray and booze on his partner’s side. A “party trick” was how he describes the way Felicity would fire a round from a revolver over his head, the loud crack signalling her victory in an argument. This night, lying in bed, he raised his leg slightly, the bullet travelling through his shin and into the wall. He knew he was in the wrong, calming Felicity down and telling police the gun went off by accident while she was cleaning it.

In January 2006, they separated after 17 years together. “I never went back,” she says. I realised the stress was killing me and I just couldn’t do it. I knew if he didn’t die, I was going to.” She’s since remarried, lives a quiet life in northern Tasmania with a gentle, steady husband and a couple of dogs. “I had a dream about Terry the other day,” she says. “I woke up and realised it was his birthday. It was a nice dream.

Terry Tangney notched up his final kill on October 18, 2006. He was 55. He saved his suicide note as a Word document on his computer, placed it on his desktop files beside his recently completed book, the book that remains on the disk that Felicity today returns to the briefcase. She picks up all the photos, all the mementos, puts them neatly inside the briefcase and closes it. She shuffles past her husband and their dog and the roaring fireplace and over to the linen cupboard, placing the untold story of Terry Tangney back on the top shelf, high up on the towels and bed sheets she uses least.