Blonde hair, blue eyes, athletic build... is Barbie really an Aryan fantasy?

The world-famous blonde, blue-eyed doll has some dark secrets in her past.

On a leaden autumn afternoon in Bavaria, southern Germany, an elderly man in a cream suit with a primrose- coloured cravat is eating egg and chips and peering intently at my face.

“I like your nose,” says Rolf Hausser suddenly. “It reminds me of my Lilli’s.” Hausser’s wife Lilli takes a sip of her lager but remains silent. We both know that her husband isn’t talking with such affection about her but about another Lilli, whom he loved many decades ago and who was taken from him for a better, richer life in America.

Hausser sinks back into silence, then returns to the topic that has obsessed him for more than 40 years. “If it wasn’t for me and for Lilli the world would never have had the Barbie doll,” he says. His wife rubs his back comfortingly but Hausser can’t be comforted and won’t find peace until his death 10 years after this meeting.

Barbie has for more than five decades been the symbol of the all-American girl; blonde, blue-eyed, with an improbably perfect figure. Her one-dimensional biography has been so efficiently marketed that most people can claim to know at least part of the story: how Barbie was invented by Ruth Handler, co-founder of the US toy giant Mattel, who named her after her daughter Barbara and launched the revolutionary doll at the American International Toy Fair in 1959. An immediate hit, Barbie soon filled US toy stores and shot to the top of the world’s best-selling toys lists, where she has more or less stayed for over 50 years. It is a simple, easy-to-digest tale that is appealing and uncontroversial.

Except that it isn’t quite accurate. Like the official histories of many stars, not all of Barbie’s story is quite as it seems. Not only is she older than her official age by four years, but Barbie is not her original name. And she was not born in the US but in the Bavarian town of Neustadt bei Coburg. Nowhere on Barbie’s personal website - or on that of Mattel - will you find the name Hausser, or the town Neustadt. It was Rolf Hausser and his brother Kurt who were the true geniuses behind Barbie; the men who produced a doll called Lilli that would go on to change her name and nationality and become the most famous doll in the world.

I first travelled to Neustadt in 1999, when Rolf Hausser was already 90 years old. He had spent much of the previous four decades riven with bitterness at being written out of Barbie’s story and was keen to tell it to a wider audience than his fellow townspeople. “I was betrayed,” he told me almost as soon as I entered the large home where he and his wife lived.

Tall and elegantly dressed, with a patrician face and eyes the colour of steel, he struck an imposing figure despite his great age. On the table, alongside cups of tea and pastries, he had arranged models and pictures of the doll that should have made his name: blonde, blue-eyed, pneumatic figurines you would swear, if you didn’t know better, were early Barbies. We talked through the day and into the early evening as he described to me the tragedy that had befallen him after his Lilli doll was taken up by Mattel, turning the US company into a household name while his firm O&M Hausser disappeared.

But Barbie’s secret story is not just a classic tale of the small-town toymaker versus ruthless corporate America. There is a darker side to her background, which I glimpsed that afternoon as Hausser swept away the pictures and models of his Lilli doll and, with great pride, brought out a pile of catalogues of the toys his firm had produced in the 1930s and 1940s, before Lilli had even been dreamed of. Alongside the farm animals, cowboys and Indians and German soldiers were other, more sinister toys: Nazi stormtroopers, black-shirted figurines, members of the Nazi elite and page after page of Adolf Hitler toys. Years later, I would find out that Rolf and Kurt had been members of the Nazi party, and that their company O&M Hausser was once dubbed “Hitler’s toy-makers”.

It was what Rolf Hausser said next that would haunt me for years. “People see Barbie as the all-American girl, but to me she will always be a German Maedchen, the symbol of purity and light,” he told me.

Later, as we drove away into the evening mist, my interpreter turned to me. “Purity and light,” she said. “You know those are the words the Nazis used to describe the Aryan ideal?”

For years I have wondered about that comment and about its possible implication. Was the doll that is so inextricably linked to American values really born out of the last vestiges of Nazism? Was Barbie really a Nazi?

Now, 14 years later, I am once more on a train from Nuremberg to Neustadt, this time to find the first chapter in Barbie’s history, and the part the Nazis played in her story.

“Don’t mention Nazis,” Frank Altrichter advises when he picks me up from the train station at Neustadt. “People are still very sensitive about the war here.” Altrichter, who has lived in Neustadt all his life, is a historian; thanks to him and librarian Isolde Kalter I am allowed rare entry into the state archives where we will find the Nazi trial papers of Kurt Hausser and those of a more sinister figure in their company. But all that will come later in the story.

Neustadt’s interest is mainly in its past: its most recent past as a border town between East and West Germany; its middle-distance past of the 1930s and ‘40s, when it enjoyed the glory of being a Nazi stronghold; and its more distant past of the 19th century, when the town was at the heart of Germany’s thriving toy industry.

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries Neustadt and its neighbouring town Sonneberg were relatively wealthy hubs. They manufactured the vast majority of Germany’s toys, most of which were produced by women and children working from home. But by the early 1920s the toy industry was struggling and unemployment in Neustadt was running at record highs. As jobs became scarcer and poverty grew, the formerly left-leaning town began looking to the right for a saviour - and found it, eventually, in Adolf Hitler’s newly formed National Socialists.

Within a few years Neustadt had become an enthusiastic National Socialist town; in 1927, Hitler held one of his early rallies here. The town would go on to host a satellite of the notorious Buchenwald concentration camp and residents’ support for the far right would continue even after the war, when Neustadt sat just inside the American zone of divided Germany. This was the town in which the toymaking company O&M Hausser arrived, under Nazi management, in 1936. And where, 19 years later, a doll called Lilli was to be created.

On one level, Barbie’s secret story is one of big business against small, of wealthy corporate America versus struggling postwar Germany. But on a deeper level it is inextricably linked with the success of the Nazi economy and the compromises a Stuttgart toymaker had to make to survive the Third Reich. Lilli had two incarnations before she re-emerged as the all-American Barbie. In 1952 she appeared as a cartoon character for the daily German newspaper Bild-Zeitung. The paper’s editor had asked his cartoonist, Reinhard Beuthin, to draw something to fill the space left by a story that had been dropped. At first Beuthin drew a cherub but was told: “Readers don’t want to see pictures of babies.” Keeping the cherub’s innocent face, he set to work on the body, taking just one hour to come up with Lilli - a sexually provocative young woman with the face of an angel. Beuthin called her Lilli because that was the first name he could come up with (although the people of Neustadt have always preferred the more enticing, though inaccurate, story that she was named after Hausser’s wife).

The Lilli cartoon was intended to be a one-off, but the next day Beuthin’s mailbag was so full that the newspaper decided to continue with it and Lilli went on to become an institution. By 1955 she was so popular that Beuthin suggested the newspaper should make a Lilli doll. She would not be a children’s toy but a figurine, an ornament that people, mainly young men, could hang in their cars. After 12 different manufacturers failed to turn his cartoon character into the doll he’d envisaged he was on the point of giving up the search when he was told about Rolf Hausser.

Rolf and Kurt Hausser were important men in Neustadt; their company O&M Hausser, which sprawled over three large factory buildings, was second only in size to the giant Siemens factory that had arrived in Neustadt at around the same time they did, in the mid-1930s - and, like the Hausser firm, it had been brought to town by the Nazis.

When Beuthin approached Rolf Hausser, the then 44-year-old was fascinated with the idea of making a doll in the shape of a mature woman. He put his chief designer, Max Weissbrodt, onto it and the company knew the blueprint was a success when Beuthin showed it to his children, who shouted delightedly: “There’s our Lilli.”

Lilli the doll went on the market in August 1955 and caused a sensation throughout Germany. Unlike other dolls, in Europe or anywhere else in the world, she was not a baby but a fully grown, modern young woman. The Haussers had given the doll flexible limbs - a radical advance in an age when the arms and legs of most dolls remained rigid. Rolf, an energetic perfectionist in charge of technical design at the factory, even ensured that Lilli could never suffer so much as a bad hair day with the design of her jaunty ponytail.

Lilli also had an impressive wardrobe of 100 different outfits, all made by Martha Maar, Lilli Hausser’s mother, who owned the phenomenally successful doll’s clothing company MMM. Thanks to MMM, Lilli also wore mini-skirts a decade before they came into fashion.

Germany’s women had changed enormously in the decade since the war when, as “women of the rubble”, they’d clung to survival in the ruins of bombed-out cities. Now they were ready to embrace life again and the Lilli doll, with her glamorous outfits, makeup and air of insouciance, became emblematic of the 1950s dawn of optimism and hope. “She was symbolic of the time,” Hausser told me. “She was sexy, young, innocent, fresh ... and independent.”

She began to sell widely around Germany before extending her range across Western Europe, the UK and, to a lesser extent, the US. But not everyone approved. Those Germans who had been shocked by the cartoon were appalled that such an immoral character had been turned into a doll - even if the doll was aimed at the adult market. Even Rolf’s wife Lilli wasn’t entirely in favour. “My mother thought the doll was too sexy to be sold to children,” their daughter Sabine Hausser told me recently.

There were also dark rumours that the figurine had been modelled on a sex doll that Hitler had ordered to be distributed to his soldiers so they wouldn’t be tempted by prostitutes and risk contracting STDs. That doll never got past the design stage but even today some perpetuate the myth that Lilli, and therefore Barbie, was a sinister incarnation of Hitler’s sex toy.

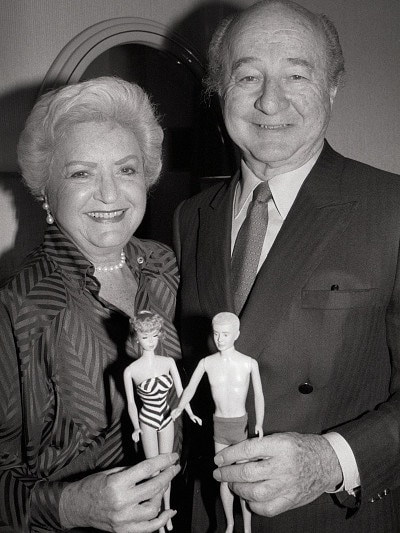

But despite the controversy, orders were coming in from all over Europe and in 1956 a Lilli doll was sitting in a shop window in Lucerne, Switzerland, when Ruth and Elliot Handler passed by with their daughter Barbara and son Ken. The Handlers’ company Mattel had begun in the 1940s making picture frames but Ruth had recently become intrigued with her daughter’s fascination for paper dolls, those adult-looking paper figures with their array of clothes. So when Barbara, then 15, pointed out the doll, dressed in ski clothes and sitting on a rope swing, Handler immediately saw Lilli’s potential. She bought the doll and took it back to the US, later sending two employees to Japan to find a manufacturer that could make a replica. By 1959 the doll had been reincarnated as Barbie. She became a hit in the US where, as she had in Germany, she symbolised the optimism of a new generation of sassy, independent girls.

The first the Haussers knew of the existence of a rival doll was when Rolf visited a toy shop in Nuremberg in 1963 and saw an array of Barbies. Convinced that they were illegal copies of his dolls, he questioned the shop owner about their provenance and was told they’d been imported from an outlet in Italy. “I was outraged,” Hausser told me. “This was my Lilli with a different name. What had these people done? Had they stolen my doll?”

Ruth Handler, who died in 2002, never denied buying Lilli and taking her back to the US. Nor did she deny that Barbie was inspired by the German doll. But she always stressed that their similarities were only “approximate” and that she had asked her Japanese manufacturers to design “something like” Lilli.

However, Mattel did not strike a deal with the Haussers until 1964, when Barbie went on sale in Germany. The Haussers were first alerted to Barbie’s arrival in their country by an ad in a German newspaper; shortly afterwards, at the 1964 toy fair in Nuremberg, they saw a large selection of Lilli’s rival doll on the Mattel stand.

By then, Mattel was selling more than 350,000 Barbies a year in the US but the Hausser brothers still had no idea just what a phenomenon their doll had become until Kurt flew to New York to investigate. On his first foray around the shops of Manhattan he quickly realised that the brothers would not stand a chance if they took on Mattel. “Everywhere my father looked - in the little toy shops, in the big department stores - they were all full of Barbies,” Ingrid Berndt, Kurt’s daughter, told me on my return visit to Neustadt. “He realised they wouldn’t be able to fight. He had to return to Germany with the news that it was already too late for the company to do anything about it.”

Rolf still hoped to sue Mattel in every European country where Barbie was being sold so that he could at least save his own corner of the market. But Kurt, who was the commercial head of the company, realised this would be futile. Instead, he suggested selling the doll’s patent. In hindsight, this was a serious mistake. Soon after the toy fair, a delegation from Mattel invited Rolf Hausser to Frankfurt to negotiate the buying rights for Lilli. “I wanted one per cent of the sale profit, but they wanted me to sell all rights for a lump sum. At 5.30pm we were still arguing but the interpreter said that she had to go home, so we had to sign within 10 minutes,” Hausser said.

In the end, he sold the world rights to Lilli for 69,500 deutschmarks - no small sum in 1964 (enough to buy a large family home) but a fraction of what O&M Hausser could have earned over the years had the company been able to stand firm against Mattel.

Rolf Hausser always claimed Mattel had cheated him out of what he believed were his rightful profits, and blamed the US firm for contributing to his company’s collapse some years later. Mattel dismissed his complaints: after interviewing Hausser I contacted the company and was told by a spokesman that the matter had been settled to the satisfaction of all parties. Former O&M Hausser staff members I spoke with also refused to blame Mattel, suggesting it was the Hausser brothers’ poor business sense that had more to do with their eventual bankruptcy.

Ingrid Berndt vividly remembers her uncle Rolf’s bitterness and her father’s depression at losing Lilli to Mattel. But she is pragmatic, pointing out that O&M Hausser didn’t have the resources to make Lilli a great success. “My father was very sad that they lost the Lilli doll but that was business,” she said. “Mattel had much bigger marketing power than we did and they had factories in countries with cheap labour forces. Here in Germany the wages and production costs were higher. Even if we had continued producing the doll it would never have been the success that Barbie is. We just didn’t have the money.”

French academic Marie-Francoise Hanquez- Maincent, a who wrote about Lilli in her book Barbie, Poupee Totem [”Symbolic doll”], believes that the reason behind the Hausser’s failure to fight Mattel had more to do with the anti-German prejudice of the postwar years than a simple story of big versus small business.

Anti-German prejudice may or may not have been the reason behind the Haussers’ failure to keep Lilli. But if Barbie’s American fans had known about her real background - or understood that without the Nazis, she may never have come into existence at all - her life expectancy would almost certainly have been much shorter.

In the mid 1930s, O&M Hausser had faced a crisis when Otto Hausser - the brothers’ father, who’d co-founded the company in 1912 - was arrested by the Nazis and imprisoned for being a Freemason. His conviction meant that he was ruled unfit to run a company and his place was taken by a dedicated Nazi and self-employed salesman called Eugen Habermaass. At his denazification trial after the war, a police report stated that Habermaass got the job at the company because of his “close relations” with the top ranks of the Nazi party. “Eugen Habermaass did not have the qualifications to take the job at O&M Hausser,” the report states. “He was a political appointment.”

Rolf and Kurt, then young men, also joined the party despite - or perhaps because of - their father’s arrest. At his own denazification trial, Kurt told the judge that, after Otto’s imprisonment, he had no choice but to sign up to the National Socialist party. “I had to take the greatest caution,” he pleaded.

Habermaass’s arrival at the company coincided with a crisis in Neustadt’s local economy. In 1935, more than 7500 of the town’s 9000 residents were on welfare and Neustadt’s mayor, Friedrich Schubart, another fanatical Nazi, began lobbying the National Socialists for help, writing to the Bavarian prime minister that without support “we may have to reckon with acts of desperation”.

The Nazis were already moving successful businesses to struggling regions and Schubart’s pleas came at just the right time. Neustadt would get two companies - the electronics giant Siemens and O&M Hausser, which until then had been based in Ludwigsburg, near Stuttgart. The Haussers had no desire to move from Ludwigsburg but they were given no choice. In 1935 the Nazi authorities told them that the army needed the company’s buildings and they would have to leave.

Letters held in Neustadt’s archives, written between Habermaass and Mayor Schubart, reveal how the two men arranged for the company to move to Neustadt and take over a factory owned at the time by the Rosenthal porcelain company. Like the Haussers, the Rosenthals were given no option but to give up their building. In their case, they fell victim to the Nazis’ brutal Aryanisation policy, in which Jewish-owned businesses were taken over by Aryan Germans, a fact Rolf Hausser seemed to have no concerns about when I spoke with him. Asked about the morality of taking over the Rosenthals’ property, he was curt. “They were lucky they weren’t killed,” he replied.

Seventy years later Ingrid Berndt, like many others I spoke to, appeared uncomfortable discussing Habermaass’s role in the company. “If Otto had been a Nazi sympathiser the company would not have been forced to move and Habermaass would not have been put in,” she stressed.

The company continued to prosper during the war, expanding into the Czechoslovakian city of Brno where, under Kurt’s management, it produced not toys but wooden shoe soles for Germany’s concentration camp prisoners and slave labourers. Back in Neustadt the company, like others in the region, also took advantage of the foreign workers transported from occupied countries, mainly in Eastern Europe, to bolster the depleted workforce. (A Ukrainian worker recently made enquiries as to how he could claim compensation for his years as a forced labourer at O&M Hausser, but was told the company is now defunct.)

Would these facts justify calling the Hausser brothers Nazis or claiming that Barbie was a Nazi doll? Perhaps. But if the Hausser family had stood firm against the Nazi party, O&M Hausser probably would not have survived the war - and Lilli, and her clone Barbie, might never have been born.

The Haussers never recovered after selling Lilli’s patent to Mattel. Through the 1950s the firm continued to prosper but by the 1960s their toys were beginning to look dated and the advent of cheap Playmobil toys in the 1970s sounded the death knell for the company’s expensively produced, hand-painted figurines. The company was declared bankrupt in 1983 and Kurt died a few years later. “I think the bankruptcy killed him,” Ingrid Berndt said. “It broke his heart.”

Rolf continued to blame Mattel for the company’s misfortune until his own death, wielding his bitterness like a weapon. Added to the brothers’ sense of failure would have been the knowledge that, while their company sank into oblivion, Eugen Habermaass would enjoy great success, creating a toy company that would eventually become a household name.

Habermaass’ connection with O&M Hausser ended in 1938 when he left to set up his own toy firm in the town of Bad Rodach, 30km away. Berndt believes he used her family’s company as a launch pad, taking the experience he’d gained there, along with some of O&M Hausser’s design ideas, to help him on his way. He called his firm Haba and it would go on to become a major international producer of wooden toys which still supplies stores around the world, including in Australia, the US and the UK.

Nowhere on the Haba company’s literature will you find a reference to its founder’s Nazi past or his role in the company that fathered the Barbie doll. Habermaass died in 1955, leaving his wife and son to run the company. Kurt and Rolf, too, are long dead and their families have no interest in reviving Barbie’s story. They would rather let her fade from their family’s history as thoroughly as they have faded from hers.