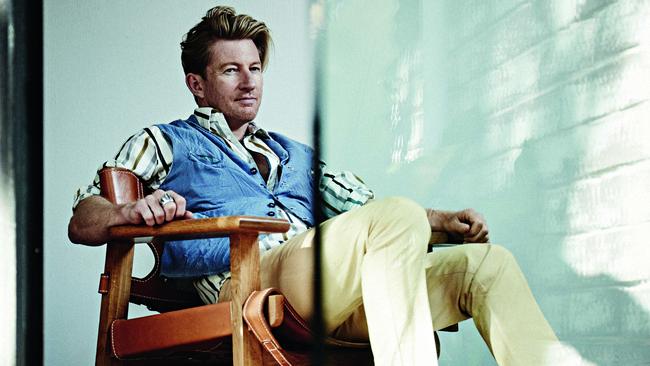

Art of the extraordinary: David Wenham

He’s a master of reinvention, with his feet firmly on the ground. How does David Wenham pull it off?

Bzzzzt. Bingo.” David Wenham’s hand comes down hard on an imaginary game-show buzzer, sending a small bowl of soy sauce sloshing. “Bento box, over here,” he says and the waitress places his lunch before him with a nod of familiarity. It’s a simple lunch taken in modest surrounds: a discreet Japanese joint with warm lighting and laminated menus featuring pictures of fish in happier times. Wenham and his partner, actor-turned-yoga-teacher Kate Agnew, come here two or three times a week. They moor themselves at the wooden counter and tackle the daily crossword while scarfing down sushi. No one bats an eyelid.

Across the road is the landmark El Alamein fountain. Its modernist sphere, like a dandelion clock, marks the point where the main thoroughfare of Kings Cross doglegs into Potts Point, neon sleaze folding into tree-lined gentrification in a tumult of exuberant urban life. This is Wenham’s Sydney. The densely packed neighbourhood is the closest Australia has to New York City and it is to the actor what Manhattan is to Woody Allen: a place that informs his lifestyle, his attitude and, now, his work. Wenham is about to debut his first film as a director and, naturally enough, it is a love letter to his home turf.

“It’s very idiosyncratic around here,” he says, with a vague chopstick wave meant to outline the parameters of his stomping ground. “It’s not just the geography of the place, it’s the people who live here, my neighbours; I love those people.” The drag queens and showgirls: loves them. The artfully upholstered older women and their lapdogs: loves them. He loves the students and sex-shop staffers, the parents with prams and the elderly lady who broke down in tears when, with much fanfare and balloons on the street, a Woolies finally opened in the neighbourhood. “She kept saying over and over, ‘I never thought I’d see the day’,” Wenham laughs. He loves the strugglers and addicts of The Wayside Chapel, the homeless charity in the Cross for which he’s served as ambassador for more than a decade. He loves the folk in the art deco apartment building he has called home for 25 years, before and after the birth of his daughters, Eliza Jane, 13, and Millie, eight. He loved a local character, since passed, whose quirks he drew upon for his role as a befuddled junkie in Gettin’ Square. “He called himself Two Four Eight: the Irate Deviate,” Wenham says. “That was his name, how he used to introduce himself, and he accused me of stealing his identity!”

On these streets, the 51-year-old is not famous as heart-throb Diver Dan from SeaChange or long-haired Faramir in the Lord of the Rings films or as the adoptive father in the more recent Lion. He’s not known as the star of Hollywood blockbusters 300 and its sequel 300: Rise of an Empire, or the just-released Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Men Tell No Tales. His neighbours don’t hail him for his roles in Australian films such as The Boys, Three Dollars, The Bank, Moulin Rouge or even, the Irate Deviate notwithstanding, for his scene-stealing part in G ettin’ Square. He’s simply David.

“My other half laughs,” he says, “because I go to the supermarket, it’s a two-minute walk, but it can take me 45 minutes because I’m stopping along the way to talk to people.” Ambling down Macleay Street now in search of a coffee to tide him over until a 3pm parent-teacher meeting, he’s just another local revelling in the beauty of the plane trees morphing in late autumn. “The leaves in these trees – literally one day they are there and the next they are not,” he says, spying a free table outside one of his go-to cafés. He orders shortbread. A sharply dressed young man leans over and asks to borrow his newspaper: “Yeah, brother. Sure.”

There’s a no-big-deal nonchalance about this part of town and Wenham has absorbed its insouciance through his pores. It allows him to glide under the radar, connecting the dots with an effortless cool, welcoming the bursts of serendipity that come with being truly in sync with your surrounds. He calls them “little moments of human connection” and suspects they harbour clues to the meaning of life.

Wenham genuinely likes people, his friends and colleagues agree, and he has very deliberately carved out an anti-A-list existence that fosters interaction with them. “You could understand why all the great success David’s had could take you down certain paths in life and it hasn’t,” says veteran Australian filmmaker Robert Connolly, who has worked with him many times since they collaborated on The Boys 20 years ago. “The whole way he lives his life and the things he prioritises – he’s an extraordinary father and a tremendous friend – show how unaffected he is by all that.” Often there’s a coldly strategic nature to the plotting of an actor’s career path but, as Gettin’ Square director Jonathan Teplitzky says, “with David you get the feeling that everything he does is an enjoyable thing. I mean, it’s his job but it’s also something he’s loved doing, every minute of it, and as a result, anything you have to do with him is a very enjoyable and warm experience.”

Wenham is known in the industry as a big-hearted trouper, generous with his support for others’ projects and always up for taking a chance on an unknown player. Teplitzky is flying high now with films such as The Railway Man with Nicole Kidman and Colin Firth, and the upcoming Churchill with Brian Cox. But the year 2000, when he was battling to make his first film, Better Than Sex, is still fresh in his mind. “David read my little script and thought it would be something he wanted to do,” Teplitzky says. “I’m personally indebted to him because he and Susie Porter coming together in my first film was a coup I could never have dreamt of; it turned it into something much more than the sum of its parts.” He and Wenham have since become good mates. “I think what’s great about him is he’s so easy to engage with,” Teplitzky says. “He’s just a really easy guy to talk to, to joke with. Often with movie stars, there’s a degree to which they need to protect themselves and be careful about how much they open up in a normal sort of way, but David has managed to have a career that embraces his inner normality.”

Wenham is, in fact, almost disconcertingly normal. Easy-going and unfailingly decent, he seems to deflect life’s vagaries with an air of blithe unconcern. But don’t be fooled. Like the duck that coasts on the surface but is actually paddling like crazy beneath, this is an actor who is deadly serious about his craft. How else to explain the intriguing complexities unearthed for his ambiguous role in Connolly’s directing debut The Bank? The “raw, visceral strength” and “extremely keen intelligence” that showrunner Scott Buck says leant gravitas to Netflix’s superhero series Iron Fist? Or the dead-eyed menace he brought to his role as suburban monster Brett Sprague in The Boys? In character for that harrowing play and subsequent 1998 film, Wenham radiated such bad energy that his co-stars found him frightening.

“The really good actors can paint in any medium,” says Red Dog director Kriv Stenders, who’s just wrapped filming a TV re-imagining of the 1971 Australian classic Wake in Fright, in which Wenham plays the deceptively hospitable outback policeman. “David can paint in oils, he can work in crayon, charcoal; he can work in watercolours. He’s got this incredibly deep-running skill set and I knew with that level of experience and control over his craft that I wanted to work with him.” Stenders saw beyond Wenham’s surface amiability to a “stealth-like quality”, an “unreadability” that would allow him to walk the requisite “fine line between being very open but at the same time being very cold”.

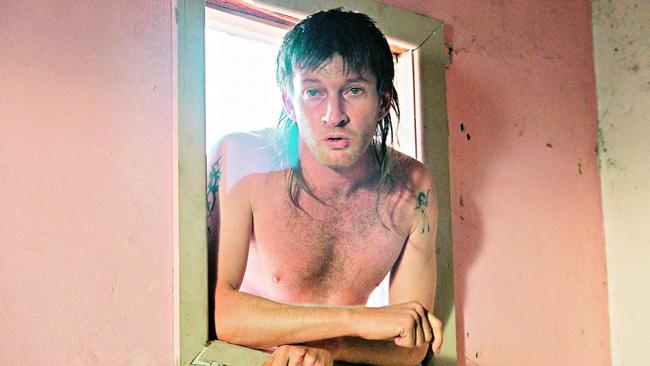

If the Wake in Fright performance is, as Stenders puts it, drawn in “very sharp pen”, Wenham’s Johnny Spitieri in 2003’s Gettin’ Square was an indelible portrait rendered in blazing neon. “I remember seeing that in the cinema and that’s when I realised this guy is the real deal,” Stenders says. “He’s one of the great actors.”

To this day, there is a subset of film fans who will collapse in laughter at the mere mention of that character, a spaced-out Gold Coast junkie with a greasy mullet and dodgy dress sense who steals the show. The famous courtroom scene, in which he hilariously wrong-foots a roomful of lawyers with a destabilising mix of street cunning and druggy bumbling, has achieved cult status. “David created a piece of comic genius,” says Teplitzky, who is in the early stages of planning a Spitieri spin-off movie with Gettin’ Square screenwriter and Gold Coast criminal lawyer Chris Nyst.

Wenham made spinning slapstick into high art look effortless. But, again, the duck was paddling hard beneath. “The day we filmed the courtroom scene, David came up to me and said – the chair he was going to sit on, did we have any other choices of chair?” Teplitzky recalls. “He said, ‘I just think that one is not a funny chair. I need a funny chair.’ At that stage, I didn’t know that when he sat down he was going to fall off the chair. So we found him a new chair and I saw him mucking about with it until he was happy with it. And that chair was just perfect. The sound of it when it fell over and the way he fell on the floor was so indicative of the character.”

Underwhelmed, too, by the outfits the costume designer had pulled, Wenham visited a nearby op shop and collated a suitably scuzzy wardrobe: loud-slapping thongs, ill-fitting stonewashed jeans and a shiny parachute jacket. “I’d seen ‘Johnny’ so many times around here, so I knew how he walked, how he sounded, and I knew exactly how he’d dress as well,” Wenham says. “I suppose it’s like, if I can use a surfing analogy, when you’re completely on top of the wave and it’s perfect and you ride it all the way in. There’s a slight alchemy to it, I suppose. It’s slippery though; sometimes you can have all the components and it just won’t come to you. But when it does it’s just fantastic.”

Wenham is the definition of a protean actor, having rarely reprised a role in nearly three decades of working across theatre, TV and film. He’s made audiences cower and cry; he’s made them fume and swoon. Interestingly, considering he has just one comedy to his credit, what propelled him into the industry was a desire to make people laugh. “During my school years, that was slightly problematic,” he says. “I caused a lot of mirth in the classroom.” Yes, he was That Guy. Growing up the youngest of seven – he has a brother and five sisters – Wenham had a room-filling energy that his teachers at the Christian Brothers High School in Sydney’s Lewisham struggled to contain, leading one to suggest he channel the high jinks into after-school drama classes. Wenham immediately found his calling and, although none of his family was theatrical, parents Bill and Kath encouraged his new passion. Christmas and birthday presents consisted of theatre tickets and boxes of second-hand books on acting.

As Sydney’s inner-eastern suburbs have defined and shaped the man, growing up in the inner-west suburb of Marrickville, back then a largely Greek community, distinguished his boyhood. “It was very vibrant, very multicultural,” he says. “I absolutely loved it.” The family home was a noisy, love-filled place so crowded his bed was shoehorned into the dining room. He recalls trundling his scooter down an adjacent laneway and hopping the fence each night to have a second, Greek dinner at his best friend’s house.

Knocked back by NIDA upon leaving school, Wenham studied at the University of Western Sydney’s Theatre Nepean, and began landing bit parts in soaps such as Sons and Daughters and A Country Practice. He supplemented his income by calling bingo at the Marrickville Town Hall and hustling lawn bowls. “The old guys would rig the meat tray each week feeling sorry for the struggling young actor,” he laughs. Wenham’s cinematic breakthrough came in 1998 with Rowan Woods’ The Boys, a chilling study of suburban evil that also marked an early entry on the resumés of Toni Collette and John Polson. “It’s a great, great film,” Wenham says now. “It’s interesting to think that it nearly didn’t get made. No funding body wanted to fund it; they thought the filmmakers were reprehensible for wanting to put such scum on the screen. And yet it’s a film that ultimately influenced a lot of Australian films over the years, great films like Snowtown, Chopper, Animal Kingdom.” The experience planted the seed of Wenham’s distaste for filmmaking-by-committee and would prove a motivating factor when eventually he decided to move behind the camera himself.

“What’s that, mate?” Wenham curls a hand around his ear and leans in to the electric-blue muscle car that has suddenly stopped beside us. We’re marooned by the side of the road outside a photo studio in Sydney’s inner-west. A taxi has been summoned but is taking its sweet time. Meanwhile, Mr Muscle Car is resting a large, gym-cut bicep on the passenger window and shouting above the snarl of his engine, seemingly oblivious to the steady convoy of trucks barrelling past.

Turns out, he has recognised Wenham from his role in 300 and is complimenting him on the chiselled six-pack he paraded in that swords-and-sandals blockbuster. “You’re great, my man!” He roars off in a haze of smoky burnout, only to be replaced immediately by a bloke in a green sedan who’s been similarly moved to risk his life in traffic to say hi to the famous actor. Wenham’s presence may go largely unremarked upon in his own neighbourhood but here, where he spent his formative years, he’s like an exotic species escaped from the zoo. He’s clearly enjoying the randomness of these roadside interactions, although the adulation makes him squirm. “By and large I fly under the radar,” he says in the taxi later, as it whisks us across town. “I think you can make a conscious decision to change if you’re famous but I’ve made a very conscious decision not to change. I’m exactly the same person, who’s done the same thing for 30 years, which is acting. Some of those have been big-budget films but it hasn’t changed how I live my life and I wouldn’t want it to.”

A streak of red and white flashes by. It’s the Coca-Cola billboard, the famous “gateway to the Cross”, welcoming him home. A desire to pay tribute to his neighbourhood while organically capturing “moments of human connection” on screen led to what Wenham affectionately refers to as his “little experiment”, a feature film called Ellipsis. Understated and charming, it is a largely improvised meander through Sydney at night with a young couple on the brink of falling in love. The film was shot on a micro-budget of $250,000 and is basically a two-hander, starring Emily Barclay and Benedict Samuel, with real-life local characters dropping in and out along the way. From go to whoa, it took 10 days to make.

“I wanted to see if there was a way of working with actors whereby a performance came along that was stripped of all artifice,” Wenham says. “So we came up with the seed of an idea, we came up with two characters, we agreed on potential thematic concerns. We didn’t necessarily know where we were going; I wanted to see what would happen and just follow the narrative as it unfolded. We were never going to get a movie like Chinatown or On the Waterfront, but I think it’s appealing; hopefully it’s a little humanist film.”

Connolly, who served as executive producer on Ellipsis, says it’s “a really beautiful film which very much reflects David’s personality. It’s got a combination of affection and mischief and playfulness and heart – all the qualities that make David such a strong actor. As [the characters] journey through Sydney, you feel the world that he observes and loves; the people he knows, the places he visits. He really knows this world.”

Wenham called in favours, shooting in nightclubs and bars owned by friends, hauling in characters he knew “from the ’hood”. The freewheeling nature of the process was liberating. “Within the machinery of filmmaking [in Australia] it becomes a little bit conventional,” he says. “I think back to when we made The Boys many, many years ago and I wanted to capture some of that energy and sense of adventure. I wanted to get the shackles off and see what was possible.”

An ellipsis is a punctuation mark consisting of three dots, signifying omission; thoughts or actions trailing into the unknown. It can ramp up suspense, gesture toward the unspoken. In its mystery and economy, an ellipsis contains all the thrill of possibility. His first film’s title is also a perfect summation of Wenham’s career at this point. Though not prepared to sideline acting just yet – “I have to pay for my hobby!” – Wenham has three “very specific” ideas for projects he wants to direct. “This way of doing things, with a very, very low budget, made me realise it’s possible for me to make films,” he says. “I really enjoy the collaboration of being a director and, obviously, you have the potential to say things that you can’t as an actor.” One gets the distinct impression that if this directing caper took off, Wenham could happily put acting on the shelf. We’ll just have to wait and see…

Ellipsis has its world premiere at Sydney Film Festival on June 8. Film critic David Stratton will be in conversation with Wenham for the Ian McPherson Memorial Lecture on June 12 at the Art Gallery of NSW. sff.org.au

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout