Why Andy Griffiths quit Treehouse to write The Land of Lost Things

His Treehouse series with illustrator Terry Denton has sold millions. But Andy Griffiths has drawn a line under that to embrace a new challenge, and he’s bringing along your kids.

The Treehouse children’s book series has sold millions of copies worldwide and turned you and illustrator Terry Denton into household names – but you’re on the precipice of releasing a whole new thing. What was the impetus for change? We were very happily immersed in Treehouse for the past 13 years. It was everything I’d been trying to do from the very start of my career: to create an absurd, surrealistic place where anything could happen, but anchored with the friendship of Andy, Terry and Jill. I never thought beyond it until the 13th book, where the poetic logic of the series kind of suggested it might be the ideal place to stop. Terry, I think, is retiring or returning to his first love of picture books and having an easier life than having me cracking the whip on him.

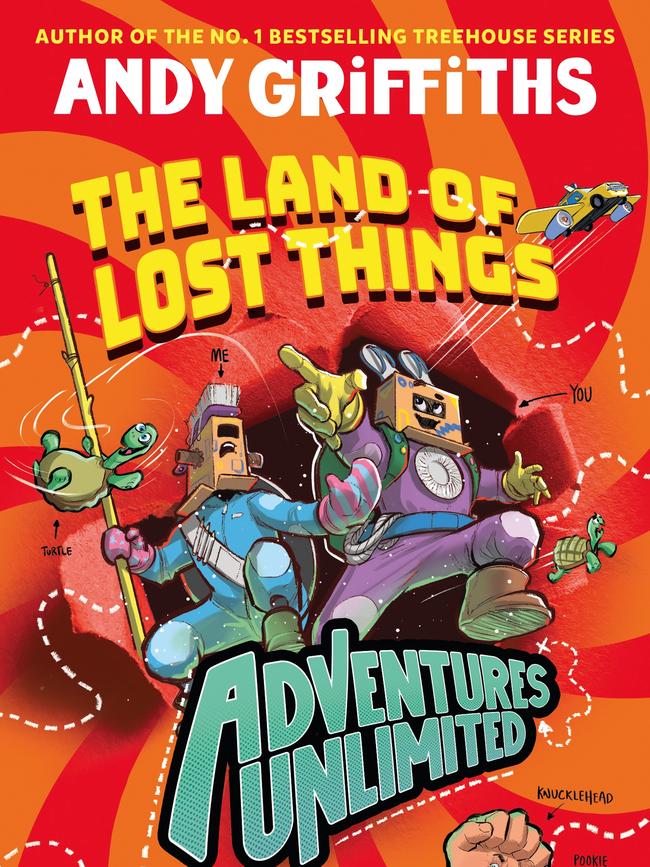

What was the inspiration for the new book, The Land of Lost Things? I’d thought maybe I’ll just sort of retire too and forever be known as the author of the Treehouse series. But there was one more thing I wanted to do, which was an idea borne from the most consistently asked question kids have asked me over the years: “Can you put me in the book?” I thought, wouldn’t it be fun to have a book where the reader is the other main character, along with myself, and we’re having adventures together.

When new collaborator Bill Hope first sent his illustrations to you, did you know you were onto something? When I can see my idea in three-dimensional form, it clarifies it for me. Bill did a picture of the You and Me characters on a boat on the river, with all this stuff around it, including a flying watch. And so I think, ‘Could that be a character that could help us in some way?’ So, it’s improvisation and it’s exciting.

Much of your work continues that great tradition of gross-out humour. Who do you see as the pioneers of gross-out humour in children’s literature? I think it’s been there from the beginning. Alice in Wonderland is my ground zero of children’s books. And there was one I had growing up called Struwwelpeter, a German children’s book of cautionary tales, and they’re violent and horrible in the extreme – the kids do the wrong thing, and they either end up dead or maimed or very, very sorry in some way. It’s a notorious book, but I loved it because it took me to those dark places, and in such an exaggerated way that it made me laugh.

What makes a good children’s book? It has to name and address some of the fears that a child might have, so, it’s cathartic and useful to them, whereas when you try to fill it with kittens, puppies and ponies, you’ve kind of defanged it.

When you’re playing in that space you risk causing offence. What do you make of the movement to retrospectively censor the work of somebody like Roald Dahl? Initially I said I didn’t see a problem with revising things that were written 50 years ago for a completely different culture with completely different social mores. I did say that. However, the revisers of Roald Dahl did it a real disservice, because they revised really insensitively and heavy-handedly to try to send a “good” message. And so I was embarrassed, having come out to defend a publisher and a writer’s right to revise material for a different time. Perhaps in this case we needed Roald Dahl around to supervise those changes. Otherwise, maybe leave it alone and put a warning sticker on the book, if you must.

Have we lost a generation of readers to the iPad? Well, we’re always competing against distractions. I grew up in the ’70s without iPads or that type of electronic distraction but we had bikes and we had permission to just stay out all day long, so we weren’t reading all day. We had plenty of opportunities for distraction. It’s definitely a challenge, and that’s the case for adults as well.

You’ve got a fantastic tattoo collection. How do you decide what to ink on your body? I’ve always loved tattoos and I was smart enough not to get them too early. The first one I got was when I’d given up teaching, I had taken leave without pay, and I funded myself for two years of full-time writing. I did go back to teaching for a while to refill the coffers, but I got a tattoo just to remind me that I’d done it. Most of my tattoos are images from books that I’ve loved. There’s Alice drowning in her lake of tears. There’s the Magic Pudding. There’s Pinocchio. Getting tattoos is another creative place to be where you’ve got skin in the game – literally. You can get it wrong but that’s the fun.

Finally, how do you get a book titled The Day My Bum Went Psycho published? They wanted me to write it! It had been a joke for a long time. Kids would ask me, “What are you going to write next? What’s your next book?” And I’d say, “Oh, I’m going to stop writing funny books, and I’m going to write something serious ... it’s called ‘The Day My Bum Went Psycho.’ It was just a throwaway line for a few years. The book opened up America for me, because the publisher Jean Feiwel, who’d been the publisher of Goosebumps and The Baby-Sitters Club, saw this controversy going on in Australia. The controversy wasn’t even about the book, it was actually about having a bum on the cover.

The Land of Lost Things is out on Tuesday through Pan Macmillan ($16.99)

We asked three young fans of the Treehouse series to submit questions for Andy Griffiths. Here’s what Anna, 10, Alasdair, six, and Lizzie, eight, wanted to know...

Is Johnny Knucklehead (the villain in The Land of Lost Things) inspired by anyone you know in the real world? - Anna There are a LOT of knuckleheads in the world – including myself – but Johnny Knucklehead is not based on anybody in particular, I swear. He’s based on my love of the word “knucklehead”.

You use a lot of talking animals in your stories – did you have an interest in that sort of thing as a child?- Anna I certainly had an interest in Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass books, which are filled with talking animals of all kinds. I guess I’ve always been fascinated by animals and the ways they are able to communicate their needs and feelings very eloquently without the need for words.

Do you have a brother? - Alasdair Well, I don’t have a blood brother, but Terry and I have long regarded each other as brothers in stupidity so I think that counts. And, although it’s early days, I reckon there are very strong signs that the illustrator of The Land of Lost Things, Bill Hope, is our long-lost younger brother.

Is the Treehouse book series ever going to end?

- Anna I’m afraid so, and in fact, it already has. Terry and I began with The 13-Storey Treehouse back in 2011. It had 13 storeys and 13 chapters and each year we added another 13 new storeys and 13 new chapters until we reached the 13th book. Since we’d been working on the series for 13 years, we figured 13x13 was the logically illogical place to stop.

How long did it take for you to come up with all the jokes in your joke book? - Lizzie As well as writing our own jokes, Jill and I got readers to send us their favourite jokes and raided dozens of old joke books for at least six months to find the exact type of silly jokes that we like. Many jokes we found were a bit old-fashioned but we reworked them to make them funny again for a whole new generation. (I’m hoping some of you Treehouse Joke Book readers will do the same thing for younger readers when you grow up!)