'He's utterly ruthless': inside the life of broadcaster Alan Jones

What’s it really like to be eaten for breakfast by radio’s ‘500-pound gorilla’? The Weekend Australian's Greg Bearup sat down with Alan Jones in late 2017 ... and it didn’t take long for him to find out.

What’s it really like to be eaten for breakfast by radio’s ‘500-pound gorilla’? The Weekend Australian's Greg Bearup sat down with Alan Jones in late 2017 ... and it didn’t take long for him to find out.

Great men and women of industry, politics, sport and business have sat in the same chair that I’m sitting in now, with a copy of the Wentworth Courier on a table to pass the time. Campbell Newman was here a few years back, prior to the disastrous 2015 election that saw him turfed out as Queensland premier and booted from his own seat. Likewise, Mike Baird. In October last year, the day before announcing his excruciating backflip on the greyhound racing ban, Baird slid quietly out of NSW Parliament House with one of his ministers for the walk of shame down to this building at Circular Quay; a press photographer had somehow been alerted and was in place to capture this humiliation. A few months later, Baird quit as NSW Premier. Two Liberal premiers charcoaled in “The Toaster”.

The Toaster is a very Sydney building, unloved and ugly, but with a view worth multiple millions. The broadcaster Alan Jones once described it as a “monstrosity”, an indulgence for the rich. He opposed its construction in the ’90s, saying it would make a mess of Circular Quay and would ruin the view of the Opera House – but hey, you can’t win ’em all. And so on a sunny afternoon, on the day Australia said Yes to same-sex marriage, I am waiting in the lobby of The Toaster’s luxury apartments at No.1 Macquarie St, Sydney.

The lobby door swings open and a middle-aged man in a tie and slacks appears. It’s David, the butler, who has worked for Jones for years. Mr Jones is running late, David says politely, but come up to his apartment and enjoy the view. As we head up in the lift I can’t help thinking, “I do hope David’s kept a diary all these years for his memoirs.”

And then we arrive. The view is stunning. The Sydney Opera House is just there, in the next room. The Bridge and the Harbour are in the garden. On a grassy hill in the Royal Botanic Garden, young folk have stripped to their undies and are splayed like starfish in the afternoon sun. Jones’s $10 million apartment is not especially large but the view triples the sense of space. A big television sits on a cabinet against a wall with family photographs of Jones on his farm with relatives, and others of him and the very famous (Bill Clinton) and the mildly famous (Michael Kroger). On the wall is a clutch of landscape paintings by Arthur Boyd and one by his brother David. On other walls are big, bold paintings of pink flowers. Versace pillows are arranged on the couches like the banners of a medieval cavalry division. Books are arranged perfectly square on various surfaces; there’s a giant tome on Muhammad Ali, Greatest of All Time, and others on artists Margaret Olley, Cressida Campbell and Picasso. The coffee table is enlivened by a vase of fresh white lilies. Near the dining table are a couple more big vases – one with orange roses, another with red. Welcome to the electoral office of the Member for Struggle Street.

‘The Alan Jones Show is only ever off-air when he’s asleep.’

Mr Jones hasn’t eaten since he got up at 3am, David tells me. He’ll need to eat straight away, if you don’t mind. There’s a clanging at the door and Jones bursts in with his 2GB producer/minder/driver, Luke Davis; Jones is in a shitty mood. He sits at the dining table with his back to the Opera House. There’s a long silence while he grapples with messages on his mobile phone. He’s been nicknamed The Parrot but as he holds his phone at arm’s length and squints I’m picturing Kenneth Grahame’s Mole. “So I’m told you’ve been ringing around people and asking strange questions,” he says at last, peering up at me from the device. “I don’t think I should have done this. The media can never understand that things are as they are; there has to be a hidden agenda somewhere.” David places a bowl of soup in front of him and he tucks a linen napkin into his collar. “Thank you, David.”

He’s intimidating. I feel like a mediocre medium-paced bowler defending a modest total; a long, sorry afternoon in the sun is looming. I know Jones was born into a family of poor dairy farmers at Acland, northwest of Toowoomba, so I lob up an easy question about his childhood, hoping to find my line and length. He belts it out of the park. “I don’t want to go into any of that,” he says crossly between slurps. “Mate, everything about that has been written a thousand times before.” I trudge back to my mark. But as the soup settles in his tummy, and his blood-sugar levels rise, his mood lifts. David places in front of him a plate with a couple of reheated lamb cutlets, three small boiled spuds and a floret of broccoli. As Jones tucks in, he moves from crotchety to reflective to charming, and occasionally, without warning, back to shitty.

What you hear on radio and see on television is what you get in person – the Alan Jones Show is only ever off-air when he’s asleep. There’s no neutral, no reverse – he’s lived life with the pedal to the metal. Alan Jones has only one gear.

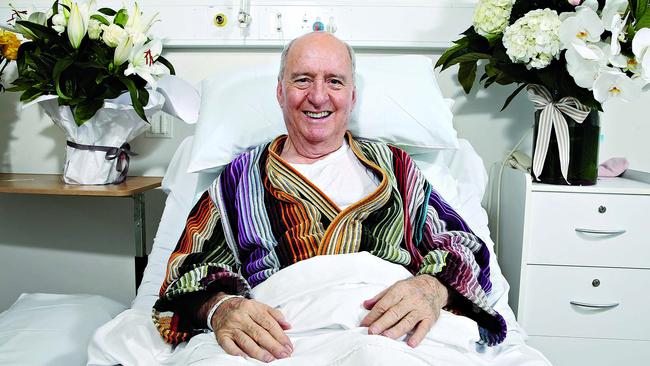

Jones always pads away queries about his age but company records reckon he’ll soon be 77. He’s in fair nick for his age, especially for someone who probably should be dead. In the past decade he’s had a brain tumour, melanoma and prostate cancer. And then, in June, he was knock, knock, knockin’… “Technically I died,” he says, picking up a chop and working his way along the bone. “Heart stopped and all that stuff.”

A year ago Jones had a major operation on his back, to treat an injury that had been troubling him since his days coaching the Wallabies. “When we beat Scotland in 1984 Billy Calcraft had to get me up into the bed,” he says, referring to the Wallabies flanker who later became a Jones-backed Liberal aspirant. “I couldn’t let anyone know I had something wrong with me. My back was hideous and it had been for years.” The pain continued for decades and he finally gave in and had the operation. “It was basically a whole back reconstruction, the longest back operation they’d done at St Vincent’s; I was on the slab for 13 hours.”

It sorted out the problems with his back but led to pain in his neck, which required three operations. He was in hospital last Christmas and into the New Year. There were complications with blood clots. He was off air for four months. “When I was in hospital the program’s ratings slumped to 12 [per cent],” he says. It’s since risen to 14.9 per cent of the Sydney market. He had to come back “to rescue the joint”.

His doctor suggested he take 12 months to recuperate. “What was I going to do, sit at home and feel sorry for myself?” On the Queen’s Birthday weekend in June he was at his farm in the NSW Southern Highlands when he fell ill again. “I wear nightshirts,” he says. “And I got these terrible sweats. I had to change the nightshirts and sheets as they were soaked.” He didn’t want to trouble his surgeon, Dr John Sheehy, as his mother had just died. And so he sweated it out for a couple of days. “Well, by Sunday night it was hideous… the teeth were chattering and I couldn’t shut my mouth. The sweat was pouring off me. So I rang him at 6:30 in the morning.” The surgeon ordered him to go straight to hospital.

Jones recalls the nurses helping him out of his sodden garments and into a fresh blue gown. “I must have fallen asleep. But at some point I woke and heard voices,” he says. “I could see about eight doctors standing around me. I heard them saying, “There’s no pulse! There’s no pulse! Get him out of here.” Was he frightened? “No. No, I wasn’t. I was quite philosophical. I thought, ‘Well this is it’.” He was in intensive care for a time. Sheehy told him later: “I gotta tell you, you knocked at the exit door, but it didn’t open.” It was an E.coli infection that had almost done him in.

‘Alan Jones’s great worry is spending too much time alone with Alan Jones.’

Those months in hospital with the operations and then the near-death experience, did it cause him to reflect on his life? “No. No, I just read. I don’t get into all that sort of self-analysis. I mean there are enough people out there analysing what I’m about and what I do. No, I just read and I continued to answer my correspondence.” 2GB’s Davis would arrive each day with emails and letters and for a couple of hours Jones would dictate his responses. “Well, we had some big issues,” he says. “I mean, I’m on the NSW Institute of Sport and I’m on the Sydney Cricket Ground Trust… I’m on the Talent Development Project, I’m chairman of that… You just can’t rule a line across them and say, ‘Well, let everyone else worry.’ I still had the energy to fire off a few salvos here and there.” Who to? “Between me and the victim.”

He still rises each day at 3am to prepare for his radio show, then fronts up once a week for his TV show on Sky News. He occasionally marches into enemy territory and charms viewers of the ABC’s Q&A; Peter McEvoy, the show’s executive producer, says some in the audience, who’ve probably only ever seen Jones on Media Watch, are surprised to find themselves agreeing with his stance on coal seam gas and globalisation. He speaks at dozens of functions a month, his life dictated by hourly diary entries.

But what’s left to prove? He’s been a speechwriter for former prime minister Malcolm Fraser. He’s had a number of tilts at political office and been rejected. He’s coached the Wallabies to a Grand Slam. He’s on Sydney’s most prestigious board, the SCG Trust. He’s been No.1 in the Sydney radio ratings for almost 30 years. His show is broadcast in full in Sydney and parts of southern Queensland and a one-hour highlights package goes to a further 64 stations across the country. He’s been one of the most powerful, well-paid and controversial media people this country has ever produced, bending prime ministers and premiers to his whims; John Howard was said to have employed a full-time staffer just to deal with Jones.

Why don’t you slow down, Alan? Why not take a long holiday and see the world? It’s the only time in our interview he shows vulnerability. “Well, that’s a very good question. I suppose it’s because… I don’t have the guts. You asked about when I was lying in the hospital, and if I was worried I was going to die… no, no, no. But I do worry… no, it’s a silly word, worry. I do ponder, I think is the word to use. I do ponder how bored I’d most probably be.” Alan Jones’s great worry is spending too much time alone with Alan Jones.

I tell him one of the many people I contacted for this profile told me he’d been commissioned by a news organisation to write Jones’s obituary, in case he suddenly pops his clogs. “What a circus,” he barks. “You can only imagine what they’d say.” Well then, what should it say? “Well look, I think Orson Welles summed it up beautifully when he said it’s vulgar to think of posterity. So I don’t even think about it. They can say what they like, and they most probably will, but I’ll be gone.” The actual Welles quote is: “It is just as vulgar to work for the sake of posterity as to work for the sake of money.” What would Orson say about working because you don’t know how to stop?

David appears from the kitchen with a coffee and a small plate of fruit. “Thank you David. What’s that ship out there?” he says, turning his attention to Circular Quay. “Is it the Three Sta...”

“Golden Princess I think it is,” says David.

So what will they say when the Alan Jones Show becomes static? Depends who you ask, of course. Jones is both reviled and admired, depending where you stand, and on what issue. Businessman Gerry Harvey, an old friend, says Jones is unique: “He’s got a brain on him that is the equivalent of the best other five brains in the country. His knowledge on sport and politics and music and everything… I’ve never met or known anyone that has his capacity. I said to him 20 years ago, ‘Your brain’s that big you’re gunna implode’.” In any social situation Jones is always the dominant character, Harvey says. “He’s always opinionated. He’s always the biggest voice at the table… he can’t help himself… it’s always interesting to be with him.” But Harvey admits he’s not a big listener to Jones’s radio program; he prefers Smooth FM.

Harvey admires Jones’s resilience, too. He says the “London incident” in 1988 (when Jones was arrested in a public toilet and charged with outraging public decency and committing an indecent act – charges that were later dropped) and the bruising he took in the 1999 Cash for Comment affair would have crippled a lesser man. “He’s survived it with consummate ease,” Harvey says. “So you have to have a super talent to be able to get over the top of some of those things.” He says everyone has a few things in their past that they’re “ashamed of”.

On the Cash for Comment affair – in which Jones and his 2UE stablemate John Laws were found to have taken secret payments to spruik projects and products – Harvey defends Jones, saying it was the practice in commercial radio. “Let’s say he wasn’t the only one. There were more… lots and lots and lots of them and it was going on before Alan Jones came to radio.” Jones has been enduringly popular, says Harvey, because he speaks his mind and he’s “not politically correct” – and that’s good for democracy. “You cannot dispute what he’s achieved, even if you don’t like him.”

One of Jones’s closest friends, horse breeder John Messara, says the public rarely gets to see Jones’s kindness. “There are literally thousands of people, including just average guys from every walk of life, and in the arts and sport, he’s personally helped; he gives away a lot of what he makes, you know.” On one of the days I’m with Jones the father of a child with muscular dystrophy has come to his studio to meet him, seeking help for a fundraiser. “What do you do?” says Jones. “Say, ‘No, I’m too tired’. You just can’t, so I’m seeing him.” Messara says people who are wary of Jones often change their minds after meeting him. “People are surprised because he is such a forceful debater, but below it all he has a very soft heart.”

‘When he spots talent, he’ll help with expenses and encouragement.’

All his friends talk of his generosity and the countless charities he supports. They also marvel at his energy. During one of the weeks I was observing him, he woke at 2.45am to prepare for his radio show. After the program he raced out the door to catch a plane to Brisbane, where he spoke at a charity lunch for the Wests Bulldogs rugby club. He then met with a Queensland minister, and had a meeting with rugby player Quade Cooper, who was captaining the Barbarians, a team Jones was coaching to play the Wallabies. Following that he met with his assistant coaches. He checked into his hotel at 6pm and spent an hour dictating his correspondence, some to be typed up and signed, some sent as emails. At 7pm he had dinner with two young athletes he mentors and supports. All of this at his own expense.

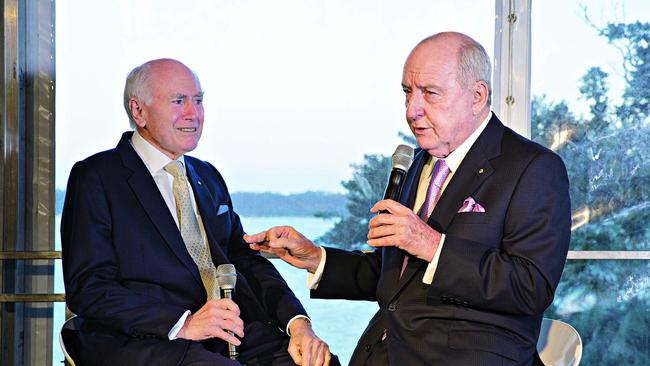

The next morning he flew back to Sydney, arriving at 11.40am for a series of media interviews about the upcoming game with the Wallabies. At 5pm he attended a charity dinner for NSW Kids in Need, where he interviewed John Howard. He left the function at 8pm to catch a 9pm flight to Coolangatta and then drove to Tweed Heads to meet with his rugby team, ready for training the next morning. A week later the Barbarians, an invitational team pulled together by Jones, were narrowly beaten 31-28 by the Wallabies, a team then ranked third in the world.

Jones selected a giant Fijian winger, Taqele Naiyaravoro, who has been somewhat on the outer in rugby circles – as has Cooper. All week, Cooper tells me, Jones had been in the big winger’s ear emphasising all the good things he could do, never once focusing on his faults. “Whatever you want to do, go out there and do it, ’cause that’s why I picked you,” Jones told him. Naiyaravoro had a blinder. So too did Cooper, who says it was the first time in years he’d felt confident in playing his natural, free-flowing game that had made him successful in the first place. “It’s left me with a great feeling,” he says.

Jones was a promising tennis player in his youth. If he’d had someone like himself to mentor him and help out with expenses, could he have gone further? “The answer is most probably yes but that wasn’t the way of the world then… it was fundamentally amateur and my parents had no money, so you couldn’t survive.” And so now, when he spots talent, he’ll help with expenses and encouragement. And for this he should be lauded.

But Cooper’s manager, Khoder Nasser – who also manages boxer Anthony Mundine and rugby superstar Sonny Bill Williams – says that while Jones has played a positive mentoring role with Williams and Cooper, with Mundine he wanted control. When Mundine first switched from rugby league to boxing in 2000 Jones pitched in to help with the arrangements for his first fight. After that fight, Jones had a meeting with Mundine and Nasser at which he said to Mundine, in front of Nasser, “Anthony, get rid of your manager.” Mundine ignored the advice. The combustible Nasser told Jones to “go f..k” himself and went on to guide Mundine through the most lucrative boxing career in Australian history.

“It is very, very rare to meet someone who works as hard as Al,” says Nasser. “He’s meticulous. He can be extremely charming and hospitable; he can really turn it on. But if he turns on you he’s utterly ruthless. That’s the flipside of Al.”

Jones has undoubtedly been a tireless campaigner for charity and a mentor to countless sportspeople and artists, but it’s the ruthless way he uses power, on and off air, for which many will remember him. One Queensland farmer who’s been involved in two causes Jones supports – the Lock the Gate movement and anti-Adani coal mine coalition – told me: “He’s as mad as a fruitcake, but if you can get him wound up and pointed in the right direction he can be useful.”

Bob Carr, the former NSW premier and foreign minister in the Gillard government, could probably write a doctoral thesis on Jones, having observed the man and his methods up close for a couple of decades, and having been in and out of favour. He has a theory about Jones’s popularity. His life, Carr says, “is a great exercise in inspired, applied self-promotion”. Jones has always been a prolific letter writer, firing off upwards of 100 missives a day to ministers and business people; in 2002 alone he sent 4500 letters to the federal government. Over the years he’s written hundreds of thousands. These letters might be about an insurance company that refuses to pay out on a battler’s claim, about a job for one of his protégés, or a faulty service that hasn’t been fixed. “Anyone who had him write a letter to a minister or a premier on their behalf is going to keep listening to the program,” says Carr. They’re rusted on. He gains listeners, too, by speaking at charity events, book launches, funerals, sports lunches… He’s spent his life spruiking the Alan Jones Show.

At his best, he “emerges as a kind of ombudsman”, says Carr, who as premier would often tell his cabinet that sometimes Jones got it right. For example, Jones was an ardent supporter of Lindy Chamberlain when much of Australia believed her guilty. But, says Carr, his judgment is sometimes appalling and he is prone to take up the cause of the first person who walks in his door, without proper investigation. Jones was a supporter of corrupt detective Roger Rogerson, now in jail for murder. “I got carried away… the decision was stupid,” Jones says now. He was on the disastrous Joh for PM bandwagon. He fanned the flames of the Cronulla riots. He said Julia Gillard’s father had died of shame (“it was secretly recorded at a private function”) and that she should be put in a chaff bag and taken out to sea (just a “figure of speech”). He was caught out in Cash for Comment (“I’ve never had cash for comment in my life”) and he lauded the work of corrupt NSW Labor politician Ian Macdonald, even providing him with a character reference at his sentencing – it didn’t help and Macdonald is now in jail.

‘John Howard admires his charity work and his mastery of detail.’

And then there is Grantham. Jones is currently involved in a defamation case with the wealthy Wagner family of Toowoomba after he linked earthworks at a quarry the family owned to the deaths of 12 people in the 2011 Grantham flash floods; a Queensland government inquiry cleared the Wagners of any role in contributing to the flood. The Spectator Australia magazine recently settled with the Wagners for $572,674 for making similar claims – the publication has paid sales of just 8000, nothing compared to Jones’s reach.

“At his worst, his ferocious dogmatism has hurt the cause of climate change and Aboriginal reconciliation,” says Carr. When you weigh up his contributions in the public square, Carr’s assessment is that “he’s done more harm than good”.

Former prime minister John Howard says he has a “positive view of Alan’s contribution” and admires his charity work and his mastery of detail. “Woe betide anyone who does an interview with Alan Jones without all the relevant facts,” Howard says. Of late, he says, Jones has been very critical of Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull and the Coalition on many fronts and he disagrees with many of these criticisms, as he does with Jones’s views on trade and protection and gas exploration. “But I take the long view… and when the chips are down, he’s been a lot more critical of Labor.”

David Penberthy, the former editor of The Daily Telegraph, says Jones is extremely charming and has a disarming way of roping you into his world view: “‘Oh David, no one understands the issues like we do.’ He has this collegiate approach where he gets you thinking that you are the only two who can see the world’s gone mad.”

The Australian’s former media writer Mark Day reckons Jones is “the greatest broadcaster of his time... he’s mesmerising, every word is uttered with passion”. He’s made himself and his station owners many millions and has proved he can hold audiences. But Day says there are big questions over “whether or not he’s been a positive or a negative for society”; his own verdict is in the negative.

A person close to former NSW premier Mike Baird told me that the bollocking Baird got from Jones and his stablemate Ray Hadley over his greyhound racing ban and council amalgamations “undoubtedly featured” in his decision to resign. “Put yourself in the shoes of someone who can earn a very comfortable living elsewhere, who has to hear his character, his religious beliefs, his ethics taken down on six hours of morning radio every day – why would you keep doing that if you are not wedded to the political game?”

Former Queensland premier Campbell Newman is still smarting at Jones’s treatment of him prior to the 2015 election. At the urging of state LNP president Bruce McIver, Newman flew down to meet Jones at The Toaster in an attempt to smooth over the relationship. It was a disaster. “It was a monologue,” says Newman of the meeting. “He just went on and on and on.” Jones believes he’d extracted a promise from Newman about halting gas exploration and halting an expansion of coal mining at Acland, his home town. Newman says he never gave him such assurances. Besides, he says, what gives “this guy, sitting in his ivory tower in Sydney… Mr Cash for Comment” the right to dictate national energy policy? According to Newman, Jones must bear some responsibility for the current energy crisis “due to his relentless scare campaign on coal and gas”.

Jones defends the stance he has taken against coal and gas. “I don’t do the bidding of anyone else,” he says. “I just believe that the place where I was brought up has been destroyed because of greed and there’s no consideration being given to the farmers and others who have been displaced with no compensation.” He uses the analogy of his dairy farming dad who would ask his mum each morning how much milk she needed before sending the rest off to the factory. “I mean 80 per cent of [our gas] is exported, it’s unbelievable.” The Adani mine is a disgrace, he says, and doesn’t pass “the stink test”. He opposes all this and yet he’s also been unrelenting in attacking the Turnbull Government over its energy policy.

Dr Graeme Bethune, CEO of energy advisory firm EnergyQuest, says Jones has had a major influence in driving up energy costs, particularly in NSW, where there is 17 years’ worth of coal seam gas “that cannot be developed due to the anti-CSG campaign”. NSW has to source most of its gas from Victoria and South Australia, at much higher cost to consumers, he says.

Jones attacked Campbell Newman mercilessly in the lead-up to the 2015 election. Newman points out that the LNP held onto every seat that was directly affected by coal and gas issues. But what the attacks did do was take the wind out of his sails on the campaign trail; every day he’d be asked questions about the latest hand grenade lobbed by Jones. “I couldn’t get my message out,” says Newman. Jones was less successful in the most recent Queensland election, throwing his support behind Pauline Hanson’s One Nation party. In a promotional video, Jones wore a T-shirt with the logo I’m sticking with Steve. “Steve Dickson’s doing a terrific job fighting” for the battlers, said Jones. Dickson, the One Nation state president, lost his seat.

‘For Jones, it’s also about winning and getting his own way.’

Baird’s former media adviser Imre Salusinszky argues that Jones does his greatest damage to Coalition governments. “Jones operates like his own unruly faction within the Liberal Party, which means that, unlike Gillard, Turnbull cannot simply ignore him,” he wrote recently. Another former senior NSW political staffer who recently worked for the Liberals agrees that Jones is much more damaging to conservatives than Labor. “If you are Labor you can ignore Jones but if you are Liberal he is talking to your base… it’s terrible for policy because everyone is always thinking, ‘How will Alan react?’ ”

The former staffer says it was “remarkable” how often Jones’s lobbying coincided with the interests of one of his rich and powerful mates, or his own interests. “Coal seam gas is all about the place he was born in, so he is completely irrational about that,” the former staffer says. Jones complains about noise from concerts on the steps of the Opera House and then rails against the NSW government’s lock-out-laws. “He’s never seen a conflict of interest he didn’t embrace.”

For Jones it’s also about winning and getting his own way. Rodney Cavalier, a former NSW Labor minister and former SCG trustee, said being allied with Jones was like “having a 500-pound gorilla on your side”. He has fought hard to maintain the power and the prestige of the SCG. There’s been a long-running tussle for stadium funding between the SCG Trust, which controls Allianz Stadium, and Sydney’s Olympic Park. Under Baird’s premiership Olympic Park was favoured. However, after intense lobbying, Jones won out – at a cost to NSW taxpayers of $2.3 billion, both stadiums will now be demolished and rebuilt, and Allianz Stadium will be upgraded first. It’s a windfall for two of Jones’s close mates, Gerry Harvey and John Singleton, who along with venture capitalist Mark Carnegie spent $80 million on a 32-year lease on 11ha at the Moore Park Entertainment Quarter, adjacent to the SCG and Allianz Stadium. They plan to redevelop the site. Jones says it was a win for common sense.

The Australian reported that at least six ministers spoke out against the stadium spending. “I can’t believe we’re doing this but I have to reluctantly agree to it,” state Treasurer Dominic Perrottet is reported to have told cabinet. Attorney-General Mark Speakman said it didn’t “cut the mustard economically or socially”. The Premier, Gladys Berejiklian, overruled them. They’d been shouted down by the loudest voice not in the room. Are you pleased with the outcome? “Well look, yes of course,” Jones says. “I mean Greg, most things are common sense.”

David comes to collect the plates from the table. Jones wipes his face and fiddles with the napkin. He complains about how much he has to do and how everyone always wants a piece of him. They just don’t understand the demands on his time. It was good to have a decent meal, he says, as he’s about to head off to a function at the SCG. “It’ll give me an excuse not to eat that Sydney Cricket Ground food. We’ve got retiring trustees.” He’ll be called on to say a few words. “I’m the longest serving trustee, I think, in the history of the ground.” We shake hands, I take one last look at the view, and David walks me to the door as Alan readies himself for another episode of the Alan Jones Show.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout