After 60,000 years of isolation, India wants to turn their home into a ‘new Hong Kong’

The fate of Earth’s last hunter-gatherer tribes – people whose way of life has remained unchanged for millennia — is in danger from India’s rapid expansionist plans. Is there any hope for them?

My journey to the tribe began at the central bus station at 2.30am. Greasy puddles reflected the Moon. Passengers picked their way between the stray dogs and drunks. The sign on the front of my ride didn’t fill me with confidence. “Spare bus No. 2 – Baratang”, it read.

Eventually, still in darkness, we set off. The bus blasted through sleeping suburbs, blaring its horn to let early risers know of its approach. Soon the concrete buildings began to thin, giving way to paddy fields and single-storey, palm-roofed houses. A couple of hours in, the sun started to rise; the jungle thickened on either side. Trees seven storeys high overhung the road, blurred with creepers. Dawn arrived.

Then, we were slowing. We’d arrived at the convoy muster point, the entrance to tribal territory. The bus halted, spilling passengers. There were hundreds of vehicles parked up – trucks, tourist vans, with our bus at the front. Food carts and chai stalls did a brisk trade; a sleepy festive atmosphere prevailed. “Our guide says there is a 98 per cent chance of seeing them,” a tourist told me.

There was a rattle of loudhailer announcements in Hindi and English. The line of cars was now half a kilometre long. Engines started. Armed police hopped in the leading vehicles, the legacy of a time not long ago when convoys might find themselves peppered by arrows. We rumbled off, passing beneath a metal gantry. Excitement shivered through the bus. It had a disquieting thrill of Jurassic Park about it.

I was in the Andaman Islands to investigate the fate of some of Earth’s last hunter-gatherer tribes – people whose way of life has remained practically unchanged for 60,000 years. The Andamans – and their twin archipelago, the Nicobars – are situated between the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Sea; their closest landmass is Myanmar. Yet through a kink of British imperialism they belong to India.

The islands are gorgeous, and the Indian government has put its weight behind them as a tourist destination. Five flights a day land in the capital, Port Blair, from the mainland, full of domestic tourists and entrepreneurs eager to cash in on the boom times. Yet the government is not only interested in developing these islands as “the Indian Maldives”. They are also key to Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s great game with Xi Jinping’s China. Great Nicobar Island, the largest and southernmost island in the Nicobars, commands the entrance to the Indian Ocean from the Malacca Strait – the world’s second-busiest shipping channel. The islands give the Indian government a commanding position over this artery of global trade.

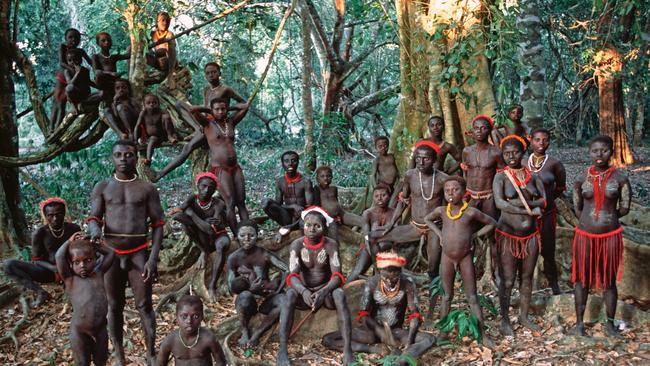

There were originally 12 tribes here. But through persecution and neglect under British rule, and breakneck development under the Indian administration, most are functionally extinct. And now, the continued expansion of Port Blair and the secretive Great Nicobar Island Development Project in the south of the island chain threaten two of the surviving isolated tribes – the Jarawa and the Shompen – like never before. Experts warn of a “genocide”, conducted under the guise of bolstering the Indian economy and securing its position as the pre-eminent superpower in the region.

People whose language no one else speaks, whose way of life is obscure, and whose relationships with the natural world few understand, may be lost for ever before we truly know anything about them. So I spent a week on the islands, learning about their plight and what can be done to stop their wholesale destruction.

If you’ve heard of the Andaman Islands at all, it’s likely because of one tribe – the Sentinelese – and an American Christian missionary, John Allen Chau. In 2018, Chau, who considered North Sentinel Island to be “Satan’s last stronghold”, was killed while trying to convert the tribe. He had bribed local fishermen to sneak him past the Indian Navy patrols that try to keep outsiders from trespassing.

His death made headlines around the world, with much of the salacious reporting focusing on the “Stone Age” tribe that killed him. These reports, though, ignored the fact that the Indian Anthropological Survey had sent expeditions to North Sentinel Island before the policy of “eyes on, hands off” was adopted in the early 2000s. In Port Blair I meet retired anthropologist Anstice Justin, who visited the island more than three dozen times with these expeditions. He told me he and his colleagues exchanged gifts of coconuts with the islanders. On one occasion, however, a shower of arrows made it clear they weren’t welcome. Despite this, Justin claims he wasn’t nervous. “We didn’t force ourselves on them,” he says.

Yet you don’t have to look far to find a history of genuine darkness on the islands. In 1857, to deal with the influx of prisoners after the Indian Mutiny, the British set up a penal colony in Port Blair. Those exiled to the islands referred to them as kalapani, the dark waters. “Crossing the waters was a form of death,” says Mukeshwar Lall, a local historian. “You lost your home, your caste, your religion. There was no return.”

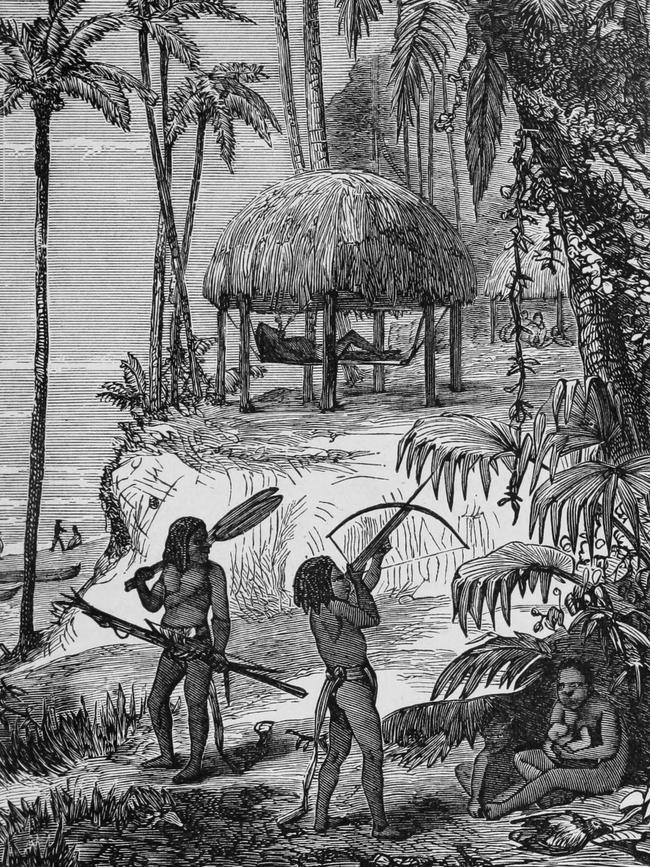

On the face of it, the Brits’ treatment of the indigenous tribes wasn’t much better, as attempts were made to “civilise” them, often to appalling effect. In addition, so-called scientific expeditions kidnapped tribespeople to study and photograph. Some experts believe an ancestral memory of these disappearances may explain the tribes’ wariness of outsiders.

There’s a danger, though, that tales of colonial cruelty obscure the current threats faced by the islands’ tribes. That, at least, is the argument of the author Jonathan Lawley, who grew up in India. His book A Road to Extinction is a rallying cry against the Andaman Trunk Road (ATR) which runs from Port Blair up the middle of the Andaman island chain, bisecting Jarawa territory. Despite being declared illegal by the Indian Supreme Court, and subject to an international campaign arguing for its closure, the road continues to transport supplies and settlers up and down the islands as well as being marketed as a tourist experience. Tour operators in Port Blair advertise day trips, selling the chance to spot Jarawas in their “native habitat”.

A Road to Extinction, though, is also a family memoir detailing Lawley’s connection to the islands. His grandfather, Reginald Lowis, worked on the Andamans from the early 1900s and became deputy commissioner in the 1930s. Lawley’s mother and aunt were born in Port Blair and grew up among the native tribes on Ross Island, which housed the British enclave.

Lawley says his grandfather cared deeply for the welfare of those he was responsible for – including the tribes. He was the first to document their decline, conducting two censuses of the islands in 1911 and 1921. “It was not realised until too late that to bring a people like the Andamanese under the influence of civilisation was altogether harmful,” his grandfather wrote.

Few people I met on the islands were willing to speak openly. Yet one area is so sensitive that even Indian nationals are banned. Great Nicobar Island lies in the far south of the archipelago, a three-day boat ride from Port Blair. It is the proposed site of the Indian government’s Great Nicobar Island Development Project.

If this project goes ahead, the consequences for the ecology of the area and its tribes will dwarf any of the impacts so far experienced on the islands. Over the next three decades, Modi’s government plans to create what is described as “a new Hong Kong” at Campbell Bay on Great Nicobar. This $14 billion initiative will see the construction of an airport, military base and a deepwater shipping terminal. A brand new city will be built to house 650,000 settlers – on an island that currently sustains around 8,000.

Great Nicobar was designated a UNESCO biosphere reserve in 2013, and Campbell Bay is a nesting ground for the endangered giant leatherback turtle. Up to one million trees of Great Nicobar’s rainforest are expected to be uprooted. The Indian government has promised to “offset” this destruction through the construction of “the world’s largest jungle safari reserve” in Gurugram on the dusty plains outside Delhi, 2000km away. There is even talk of transporting Great Nicobar’s native fauna, including 20,000 coral colonies and saltwater crocodiles, to this as-yet-unbuilt reserve.

“It’s completely crazy,” says Callum Russell of Survival International, a British NGO that campaigns for the rights of indigenous peoples. “The whole thing is a fever dream of someone in an office in Delhi.”

The Nicobar Islands are also a seismic hotspot; the epicentre of the earthquake that triggered the 2004 tsunami, killing 230,000 people across the region, lies close to Campbell Bay. The proposed location of the deepwater terminal has experienced nearly 444 earthquakes in the past 10 years.

The project also poses an “existential risk” to the island’s two indigenous tribes, the Nicobarese and the Shompen, says Sophie Grig of Survival International. The NGO has co-ordinated a letter, signed by 39 genocide scholars, which argues that the Great Nicobar development project will be a “death sentence” for the tribes.

One source with close knowledge of the project tells me that the 130 sqkm of primary jungle expected to be chopped down to make room for the new city will encompass at least three Shompen stomping grounds. In fact, the first draft of the government’s environmental impact assessment recommended that the tribes be placed in a reserve, penned behind barbed wire. “[World leaders] must tell the Indian government that what they are doing really is genocide,” the source argues. “They are killing their own people. It’s a monumental folly.”

Work on the project has reportedly already begun. “In a few more days, they will start chopping down trees,” my contact says.

The fate of the Jarawa perhaps provides the best-case scenario for what might happen to the tribes of Great Nicobar Island should the project continue. For the past few decades, the Jarawa have had some contact with the outside world, largely through the ATR. The road has exposed the tribe – who number about 400 – to noise, disease, pollution and gawking tourists. “Imagine if someone split your home in two and brought tourists to look at you washing in your bathroom,” says Denis Giles, editor of the Andaman Chronicle. “Tour operators sell this illegal, hidden package: ‘Travel this road and see naked tribespeople from the Stone Age.’ They are treated like animals in a safari park.”

The Jarawa are supposed to be safeguarded under the 1956 Protection of Aboriginal Tribes Act. It carries a penalty of seven years in jail for any interaction. But Giles has spent two decades recording near constant violations of this law. He has also reported on sexual abuse of the Jarawa and drug addiction among the tribe.

When I visit, it seems largely business as usual: tourists still come to see the Jarawa, they are simply a little more subtle about it. Now, guides advertise day tours to Baratang, a small town about four hours’ drive north of Port Blair on the ATR. I decide to join one and make the journey through tribal territory.

In Port Blair, the idea of a hunter-gatherer tribe living less than 30km away felt ludicrous. But here on the ATR, deep in the jungle, it is less so. Three convoys a day are allowed to cross Jarawa territory from either side; in reality, this means a stream of heavy traffic blasting along the road. It’s striking how busy the roadside is; construction workers amble along it; diggers and tractors clutter its shoulders.

When we finally see the Jarawa, I almost miss them. The bus snarls past heaps of earth blocking the road. Then, at once, there they are: two boys standing by the side of the road, while a smaller child squats on the steps of an earth mover. The boys wear grass skirts, their dark faces made up with vivid patterns of white paint. They carry whisks and beat listlessly at the air. I can’t tell if they are swatting flies, or simply bored. We shoot past so quickly that, were it not for the startle of excitement inside the bus, I might have dreamt them.

There is no profound flash of connection. To them – if they see me at all – I am simply another eager face at the window. I flush with adrenaline, then immediately feel dirty. I sit back with a sour taste in my mouth. For their part, the boys seemed unaware of the commotion they caused. Instead, they stared ahead. It was as though they were looking through the traffic, to the trees on the far side of the road.

The promised money and jobs of the Great Nicobar Island Development Project have been welcomed by its Indian settlers. But Vishvajit Pandya, an anthropologist who has worked on the islands, argues they are naive. “[They] need to wake up. I’m not denying economic development is needed, but it cannot come at the cost of Great Nicobar’s ecology and indigenous tribes,” he says.

My conversations about the project are shadowed by the secrecy that surrounds it. People drop into whispers; one contact half-jokes that we should switch off our phones to prevent the government tracking us. The development, most suggest, is less about giving a neglected outpost an economic boost, and more a geopolitical power play by the Modi regime.

“Strategically, [the project] means the government can occupy the entire Bay of Bengal,” Denis Giles says. “When it comes to the Chinese, strength respects strength.”

“If you’re in a taxi, you can stop and give the Jarawa bread, crisps. But don’t worry, they are not dangerous. They don’t speak our language, they’re not equal to humans,” an Indian tourist had told me on my arrival at Baratang. He was also travelling alone, and had taken me for lunch. Later, we see two Jarawa men hitching a ride in the back of a cement truck on the ATR. This prompts the Indian tourist to show me a video he had taken on his phone of a Jarawa settlement; his guide, he explains, illegally steered them close to take photos during a boat trip to see Parrot Island, a tourist destination.

The study and protection of the islands’tribes falls between two bodies – the Anthropological Survey of India and the Ministry for Tribal Welfare. One steamy afternoon I spend a fruitless few hours trying to speak to someone at the ministry. At first, I am told no one is available. Later, I’m told no one is authorised to talk.

The ministry is “a hollow organisation”, says Pandya. It has merely kept the Jarawa dependent on imports of food and medicine, he argues. He cites the example of sanitary products, which the ministry handed out alongside toothpaste and rice. At first deliveries were patchy – then they stopped entirely. So Jarawa women began to fashion tampons from plastic bags chucked out by travellers on the ATR, stuffing them with leaves. Infections became rife.

“What is introduced must be sustained,” he says. “You cannot do it for one month, one year and forget about it. The future of these tribes of these islands is very bleak. There is so much we can learn from these people, these places, before it all becomes Starbucks and pollution.”

It’s difficult to speak to a tribesperson. But on one of my final nights, I have a breakthrough. Via a mutual contact I arrange to speak to a prominent tribesperson who has built a business helping those who wish to remain isolated to liaise with the outside world. He is wary; our rendezvous location and time change. Eventually, I’m driven in an SUV to an office in Port Blair. He’s willing to talk, he says, but only if I promise to reveal no further details about him.

Does he feel the ministry has the tribespeople’s best interests at heart? “Yeah … maybe,” he replies. “I appreciate their sincerity, they are trying to do something. But sometimes, nothing happens. Tribespeople know how to survive. They have their own culture, language, traditional knowledge – they are already experts in their own way. They are already in the mainstream in their own perceptions. But the modern world won’t accept it. They must adapt only by losing their own culture. It’s unfair.”

Would the Great Nicobar Island Development Project disrupt the tribes? He laughs bleakly: “Yes, I think so. Any project which interrupts their way of life will be traumatic. I’ve seen what’s happened on other islands. There used to be 12 tribes. You see those whose land has been developed, and those whose land hasn’t. On one side, there are smiles. On the other, no smiles. The land is their life, the forest is their life. Until people respect that, there will be no happiness.”

He glances around the office, where photos show him meeting dignitaries and tribespeople. He looks at me hard. “You ask a tribesperson, ‘Were you occupied?’ and he will say, ‘No, the outsiders were our guests. We welcomed them’.” He pauses, then continues: “That is the difference in perception. But until people understand it, the tribes will never be heard.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout