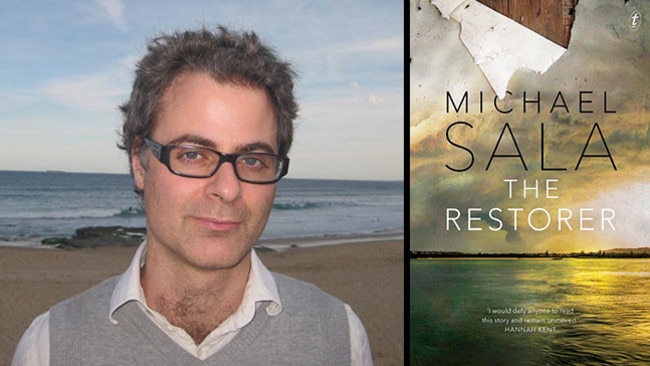

The Restorer by Michael Sala: tension builds as a family crumbles

A house restoration is the basis of this remarkable novel, but it’s the family that is built on unstable foundations.

In the opening of Michael Sala’s second novel, a family arrives in Newcastle, NSW, in 1989 to restore a dilapidated inner-city terrace. But it is not only the restoration of the house that is at stake in this remarkable novel. The family itself is built on unstable foundations.

The Restorer is narrated from the alternating perspectives of Maryanne, who has reconciled with Roy after a separation, and their teenage daughter Freya. Despite this, the overbearing force within the novel is Roy, ‘‘the restorer’’ of the title. Sala depicts Roy with a physical intensity as he navigates ‘‘that fine line … between fear and anger’’.

Maryanne empathises deeply with Roy and ‘‘the stony, empty pathways that led from one part of his childhood to the next’’. Roy is a man incapable of empathy, even for his own son, eight-year-old Daniel.

Freya tells us that ‘‘some small fuse had been lit inside him and was burning its way through his nerves’’. The novel works that way too, its tension building incrementally.

Maryanne is a skilled nurse who is committed to giving Roy another chance for the sake of their family. Around him she is constantly vigilant and begins to doubt her judgment, wondering whether it is ‘‘her own fear … creating something’’.

Nonetheless, Maryanne isn’t portrayed as a victim but as a compassionate mother who responds to the world in a way that aligns with her personal experience. Sala traces the flow of her thoughts to give us insight into her tangled emotions: she imagines the ‘‘exhilaration’’ of leaving Roy again, offset by ‘‘the bleak tension’’ of what he would do.

Freya is on the verge of womanhood and finds it difficult to understand her mother’s choices. On her first day at her new school she feels ‘‘as if she weren’t quite in control of her limbs’’ and Sala captures her awkwardness with an uncanny authenticity.

Freya starts to act out in an effort to assert her independence, placing herself in dangerous situations as a means of identifying her limits. She starts drinking and taking drugs, staying out late and shoplifting, which ‘‘felt more like falling than anything else’’. She also finds herself attracted to an older boy, similar to her father in demeanour, with ‘‘hard skin and hard edges, an adult’s heft’’.

Sala builds the novel out of the fabric of his character’s lives: Freya at school, the family at work on the house or eating dinner, Maryanne at work. He has a flair for describing details in a way that captures their lived experience: ‘‘laughter that seemed to change direction like a lunging flock of birds’’ or the way ‘‘the warm crackle of the record player scraped out a song’’.

His scenes are immersive, drilling into experience, and he is gifted at writing bodily sensations, which gives us a feel for his characters as physical beings, ‘‘the cold memory of the water like an echo in her bones’’.

Newcastle, where the author lives, is also vividly drawn, with its beaches and bluffs offset against the industrial stacks on Kooragang Island. As Roy painstakingly restores the house, the novel marches towards the inevitable earthquake, threatening to undo his work.

Sala’s first novel, The Last Thread, was based on his life. He was born in The Netherlands to a Greek father and Dutch mother, and came to Australia in 1980. The book won the NSW Premier’s Award for new writing and was the regional winner of the Commonwealth Book Prize. It showed Sala’s ability to mine personal experience for insights into how trauma shapes personality.

There are strong echoes between The Last Thread and The Restorer: the violent patriarch, the belittled younger son and the mother who tolerates more than she should. Both are concerned with emotional inheritance and patterns of behaviour, as well as how those cycles are broken. Much like David Vann, who exorcised the event of his father’s suicide through his violent fiction, Sala’s prose gives us the sense of a personal reckoning taking place.

But there is more at stake in The Restorer than the anatomy of a single family. Sala ties his novel into the tumultuous events of 1989 — the student protests in Tiananmen Square, the fall of the Berlin Wall and closer to home the murder of 14-year-old Leigh Leigh in Stockton Beach, NSW — as though the family crisis echoes outwards. Moreover, he examines the dark undercurrent of masculinity, whose effects within the family home are often invisible from the outside.

In one unforgettable scene, Roy’s anger escalates in an encounter with another driver while the family sits in traffic. Roy ‘‘hit him again and again, sharp precise blows, like he was building something’’. The building metaphor is quite deliberate: the idea of the home, Roy’s insistence on restoring a structure that is broken, aligns with what Sala is saying about families. The family home is meant to offer protection to the vulnerable; Sala examines what happens when it is unable to fulfil that role.

As the novel progresses its focus narrows, closing in on the reasons for Maryanne’s separation from Roy, and a gradual claustrophobia takes hold as we learn what Roy is capable of. Sala manipulates our expectations so carefully that the novel’s conclusion, though inevitable, comes as utterly devastating.

If Maryanne shows us how an intelligent and compassionate woman can find herself tied to a violent relationship, Freya offers the possibility that, if confronted, patterns of destructive behaviour may be broken.

This is powerful, poetic, extraordinary fiction; the family unit and the city crumbles around his characters, but Sala never falters.

Gretchen Shirm is a writer and critic. Her most recent book is the novel Where the Light Falls.

The Restorer

By Michael Sala

Text Publishing, 352pp, $29.99

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout