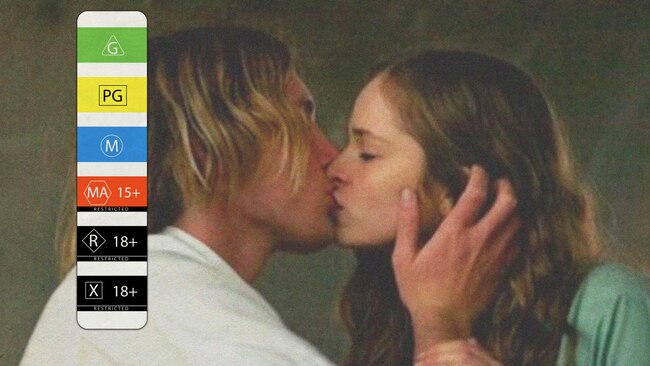

Classification code: Consent to be called out

The current classification does not distinguish between sexual violence and intimate scenes where consent is not captured in production.

The current classification does not distinguish between sexual violence and intimate scenes where consent is not captured in production.

Activists are pushing for consent to be included in the film and TV classification code in a bid to bring screen productions in line with affirmative consent laws sweeping the country.

Consent Labs, an independent sexual education provider, has launched a petition to include the term “lack of consent” in the Australian classification system, in a global first.

Currently, the classifications board uses six elements when making a grading, including violence and sex, but does not specifically draw a distinction between sexual assault and the absence of on-screen affirmative consent.

Affirmative consent requires both parties' explicit, informed, and voluntary agreement to participate in a sexual act. NSW has legislated affirmative consent, and Queensland and Victoria have passed bills.

Angelique Wan, CEO and Co-Founder of Consent Labs, told The Oz the move comes after a study commissioned by the education provider found three in five Australians struggled to identify the provision of affirmative consent in the media they consumed.

“There's still that disconnect and a lack of understanding around what consent looks like in practice or in reality,” Wan tells The OZ.

“This will help audiences think about whether what happened on screen was consensual or non-consensual and then critically analyse whether they want to mirror those things in real life.”

A spokesperson from the department of classifications told The Oz in a statement that the board already considers consent a part of their criteria, and “generally identifies non-consensual sex in a film with consumer advice which included ‘sexual violence’.”

"It is unclear how the concept of ‘consent’ could be introduced as a separate element. However if it was introduced as a classifiable element the same considerations would determine a classification,” they added.

The current classification does not distinguish between sexual violence and intimate scenes where consent is not captured in production.

Wan said current classifications neglect to address the provision of consent outside of penetrative interactions, and the petition will look to include a broader conversation around all elements of intimacy.

The Board noted a change to the classifiable elements would require a change to legislation.

Wan suggests despite positive moves toward improving Australia’s education around consent, a nationwide survey commissioned by Consent Labs revealed the influence of on-screen portrayals of sexual encounters calls for the need for further action.

In a survey of 1100 Australians aged 18 - 44, the study found a quarter of Australians were unable to define consent and two in three (63%) Aussies weren’t clear on what the laws are around sexual consent.

Three-quarters of Australians agreed that explicitly calling out non-consensual acts on screen would help educate viewers, while 71% believed classifying these scenes should be a legal requirement moving forward.

“I think the depiction of consent - whether it’s in a comedy or a romance film - has a huge influence because it's so subliminal to our everyday actions. Even if you're not consciously thinking about it it's slowly getting ingrained,” Wan said.

Wan says the petition aims to help the audience's understanding of the provision of consent, but hopes it will have a ripple effect on the entertainment industry overall.

“There's a lot more conversation happening about the fact that consent has been widely absent from entertainment, and a disconnect from reality over how sexual content is filmed versus how it is in real life,” she explains.

“I hope this move improves industry standards, but for now, our focus is really on for the viewers being able to clearly identify what is consensual behaviour and what isn’t.”