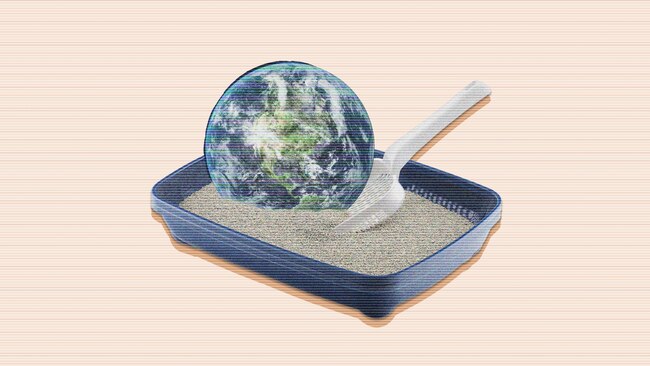

Cat litter could save the world

Your cat's toilet could help off-set cow farts

Your cat's toilet could help off-set cow farts

Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the US say they have found a potent new tool in the fight against global warming.

It is basically cat litter.

They soaked an odour-eating clay used in cat boxes in a copper solution to create a compound that they say snatches methane from passing air and turns it into carbon dioxide, a much less harmful greenhouse gas.

The Energy Department gave the researchers $2.8m to design devices with the compound that can be attached to vents at coal mines and dairy barns, which are big methane emitters. The idea is to alter the chemistry of emissions before they hit the open air, like a catalytic converter on a car.

MIT’s researchers say their findings have the potential to greatly reduce the amount of methane in the atmosphere and slow warming temperatures on the planet. The discovery could also create another possible application for zeolite, a clay used to clean up some of humankind’s nastiest messes, from driveway oil spills to the 2011 meltdown at Japan’s Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant.

Zeolite’s magic is in its tiny pores, which enable it to function as a filter or a sponge, depending on the chemistry. It is used to strengthen cement, improve soil, eliminate smells, keep fruit from ripening and soothe cow stomachs. Keeping methane from the atmosphere could be its biggest job yet.

Known commercially as natural gas, methane is many times more effective at trapping heat in the atmosphere than carbon dioxide, which is the byproduct of burning methane at power plants, on stoves or atop oil wells. A lot of methane wafts into the atmosphere at concentrations that are too low to burn.

Besides coal mines and belching cattle, methane seeps from swamps, landfills, manure lagoons and melting permafrost. It bubbles up from lake bottoms and escapes pipelines and drilling sites. Termites are notorious emitters.

Nature’s ability to process methane has been overwhelmed by human activity, from hot showers to hamburgers. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration scientists recorded the biggest annual increase of atmospheric methane on record last year, to an average concentration about 162% greater than preindustrial levels.

Desirée Plata, an MIT professor leading the work, said that if emissions from the world’s coal mines were filtered through copper zeolite, methane could stop accumulating in the atmosphere. If methane emissions were reduced by 45% by 2030, projected warming would be reduced by a half-degree Celsius by 2100, according to climate experts.

A half degree is nothing to sniff at.

The United Nations’ advisory body on climate change says the difference between average global temperatures rising 1.5 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels and 2 degrees Celsius (a 0.9-degree Fahrenheit gap) equates to ecological mayhem. Species loss at twice the rate for plants and animals, triple for insects. Crop yields down 7% instead of 3%. Hardly any coral reefs survive.

Emissions-reduction plans are falling short of targets set by 2015’s Paris Agreement on Climate Change, adding urgency to develop technologies that can help slow warming. The World Meteorological Organisation said last week that the odds are even that global average temperatures will temporarily exceed 1.5 degrees above preindustrial levels during the next five years.

In an MIT lab crowded with gas cylinders and scientific instruments, jars of cloudy, sky-blue soup sloshed around a mechanised spit, exchanging ions. Nearby, doctoral student Rebecca Brenneis poured the mix - water, copper nitrates and a few grams of zeolite - over a glass-fibre filter. The solids cracked as they dried, like a desert after rain.