True warrior Nadal found greatness in dark of SW19

It’s an impossible job to stitch together a highlights reel of one of the most epic of careers. Too great, too vast, too long-lasting, too significant. The best solution is to rewind to July 7, 2008.

Some genius at the BBC will have made a decent fist of it, because they always do, but really it’s an impossible job to stitch together a highlights reel of one of the most epic of careers. Too great, too vast, too long-lasting, too significant. The best solution, then, is to rewind to July 7, 2008.

People used to say John McEnroe was in the greatest Wimbledon final ever. McEnroe himself went further when describing Rafael Nadal versus Roger Federer that day in 2008. He went the whole hog and called it: “The greatest match ever played”. It was certainly the greatest tennis match I ever saw.

One thing you learn about the Wimbledon men’s final is that the longer the match goes on, the more seats in the press box start to become available. That’s because the writers are getting close to deadline and some therefore prefer to write from the media centre.

I wasn’t writing that day. I was watching the match at home, my initial interest growing gradually as the sequence of circumstances accumulated into something you couldn’t take your eyes off: the delays owing to the rain and the way that toyed with the narrative, the confident surge ahead by Nadal, the fact that you couldn’t believe what your eyes were telling you, that here we were seeing the destruction of Federer, and then Federer rewarding that disbelief: “No I’m not going to let that happen”. All that and the mesmeric quality of the tennis being played by both men.

At what point, I cannot recall exactly when, I said: “Sod it, this is too good, and there are going to be seats opening up, I’m going. The All England Club is five miles from me and on a bike it’s mostly downhill.” Thus did I get to bear witness.

It wasn’t quite “the Nadal final”. Not like “Botham’s Ashes”, or “Jonny’s drop-goal”. There have been too many “Nadal finals” for Wimbledon 2008 to steal the title and the inverted commas.

Yet it was historical. In a sporting sense it was. It felt like the ultimate summit meeting. Federer had been world No 1 for 231 weeks. He had been peerless. He had five consecutive Wimbledon titles. Nadal had already accumulated four consecutive French Opens, but he was, it seemed, only the master of clay. Then came 2008, the year of the great convergence. Federer couldn’t close the gap on clay. In the 2008 final at Roland Garros, Nadal humiliated him; Federer won four games in the entire match. On grass, though, Nadal was getting closer: he lost a four-set final in 2006, a five-setter in 2007. This heralded the zenith of one of sport’s greatest rivalries. Was it here, in 2008, that Nadal would finally catch him? I am always intrigued about Nadal, the leftie, in part because his left-handedness contributed to those furious battles with Federer: warrior versus artist, left versus right, the leftie firing those high spinning missiles at Federer’s backhand, his most elegant of shots. But in part, too, because Nadal is actually a rightie.

He writes right-handed, brushes his teeth with his right. He plays golf right-handed too.

As a kid, he was double-fisted off both sides. Then Uncle Toni told the boy that he had to go one way or the other and that, actually, he was going to be a leftie.

This is a great sports topic, particularly for Canadian ice hockey players. The most famous of the lot of them, Wayne Gretzky, was right-handed but played as a leftie. Golf? The only Canadian man ever to win a golf major was Mike Weir; he played as a leftie but was right-handed too.

The minority of the left-handed is around one in ten. The percentage of leftie ice hockey players in Canada is far higher: 20-30 per cent. The main reason is that when kids start to play, many are encouraged, if they find it easier, for control and power, to have their more dominant hand at the top of the stick.

Uncle Toni has always been dismissive when asked if that decision to put the racket in Nadal’s left hand changed the course of history. Would Nadal have made it right-handed? Of course we will never know. The upshot, though, was that Nadal learnt to play the harder shot – the backhand – led by his dominant hand, which is why people have said he has two forehands. For the purposes of chasing Federer, it made for a perfect competition, the one player perfectly suited to probe and test the other, clashing but complimentary styles. A rivalry of epic proportions.

On July 7, 2008, Nadal was able to assemble so many aspects of the mastery that would drive him for another 16 years. He showed that he could adapt: he wasn’t “just” the ultimate clay-court slugger. He revealed the temperament of the great sports stars: the ability to conjure the magical shots when they were really needed. Federer had that, too, that day, which is why it felt like something great, something special.

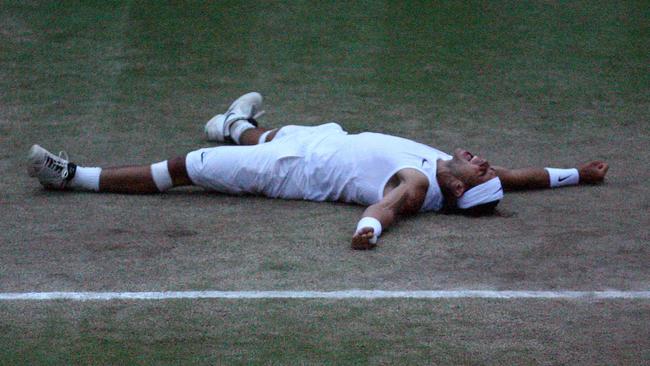

And, of course, Nadal exhibited that warrior spirit that always defined him. He went two sets up and yet was dragged into a fifth; he failed to convert either of two match points in the fourth and yet had the mental strength to finish it off finally in the fifth.

The Tennis Podcast once did a special Nadal-focused show in which they asked the question: “If you had to pick one player to play one single set and your life depended on it, who would it be?” And their answer was: “Why would it not be Nadal?” That is certainly what we saw on July 7, 2008.

I’d like to lace into this recollection of that “greatest match” memories of certain rallies and particular shots. If you google it, you can find those aplenty. But my memory doesn’t work that well; it holds on to the feeling of the occasion, the sense of what it was to be there, the inescapable conclusion that something extraordinary had just taken place.

It also, often, is guided by how moments are preserved photographically, particularly by my friend, the Times photographer Marc Aspland. One of the reasons that day was unique was that it went on so long it finished in the near dark.

While this contributed to the feeling that we were witnesses to a special occasion, it also gave the setting for some of Marc’s most beautiful black-and-white work. His crowning shot is of Nadal holding the trophy above his head, the sky now so dark that some of the crowd are indistinguishable, the Centre Court clock reads 9.26 and another flash gun has caught Nadal in a light that frames him like a kind of god.

Some time, many weeks later, Nadal came to The Times offices and James Harding, the editor, presented him with a framed print of that shot. To this day, that picture hangs in his home.

It is but one physical memory. He has so many of them; three decades of them, a highlights reel that could go on for weeks. But for one snapshot, go to July 7, 2008, one of the greatest days of one of the greatest of sportsmen.

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout