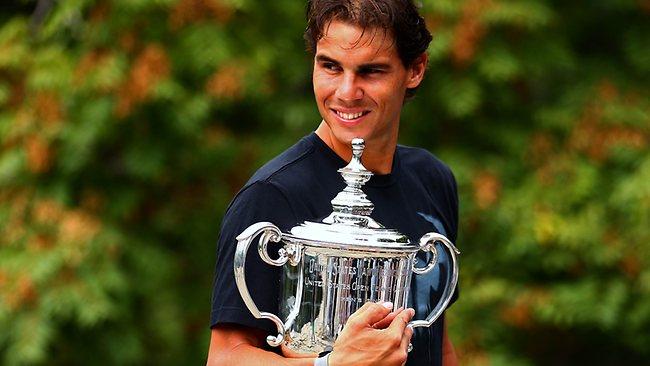

Rafael Nadal shows a refusal to lose with US Open triumph

HIS gritty, brilliant performance in the US Open final shows that the force is with Rafael Nadal again.

RAFA doesn't give up. That is the heart of the matter, the bleeding obvious essential truth about Rafael Nadal. You only have to watch him play a single point. More or less any old point will do: he will rush about from side to side, and even if his opponent is plainly dominating, he will keep pounding away.

If he is outsmarted with a drop shot he will give it the charge, and if he's beaten cross-court he will chase the ball as if to the Earth's ends, like an obsessive-compulsive border collie. And more often than not - more often than seems strictly possible - he will win the damn thing.

Why is it, then, that we give up on Nadal so often? It seemed that Nadal was beaten at least twice in yesterday's memorable US Open final against Novak Djokovic, but in the end he won going away. Wise tennis observers have wagged their heads with sadness over his waning powers at least three times in his career. That's it: it was great, but it was never meant to last. Nadal's game was never built for the long haul. Time to give up on him.

But at Flushing Meadows he claimed his thirteenth grand-slam title, which puts him third all-time, behind Pete Sampras and (remember him?) Roger Federer. Nadal is still only 27, do you think he'll go past Rodge? Piece of advice based on observation: don't write him off.

Nadal was written off as a serious force in men's tennis as recently as this summer. He had just made an heroic comeback to win the French Open for the eighth time, but arrived for Wimbledon in poor shape and went out in the first round. Bring out the obits. It's the knees, the knees, the Achilles' knees of Rafa, both battered by tendinitis, ruined by that relentless never-give-up, court-crisscrossing style of his. Obviously, the victory in Paris was his last hurrah, glorious, but costing everything. Well what a way to go, eh?

Nadal didn't see it that way. Poor soul, he was crazy enough to have a go at the hard-court season, the most unforgiving surface of all for his poor old knees. Surely his only possible future was as a clay-court purist. Those hard courts would finish him off for good.

Er, not quite. He managed 22 successive hard-court victories without a single defeat, winning three tournaments before going into the US Open and battering his way to yet another victory. His season has been a quite startling achievement and he has two of the four slams on offer this year.

He's not washed up, he's actually, never mind the rankings, the best player in the world. It seems that the two states are easily confused.

He missed the US Open last year and the Australian Open that followed last January, and that was when the serious writing-off went on. Back in 2009 he had missed Wimbledon, and that was when people first got the taste for the fading-force theory. Instead, Nadal is a living monument to Nietzsche's belief that what doesn't kill you makes you stronger.

Take that rivalry with Djokovic, one that is now a 37-match series. Nadal had the upper hand until Djokovic burst through at the end of 2010 and became a serial champion. Djokovic reeled off seven successive victories. It seemed that the old order had changed, that Djokovic was now the boss. Nadal had begun to look dismayed and disheartened. Knees or no knees, it was surely time to write him off.

Or not, of course. Nadal came back at him in 2012. This year, I saw their glorious semi-final in Paris, a match in which both players were at their best at the same time for extended periods, producing a series of rallies that made you wonder that such things were physically possible. And Nadal prevailed and went on to win the final.

With two such great talents - talents that dovetail to create extraordinary and protracted matches - there is never total dominance in a career, or in the course of a single match. You can look at yesterday's match and find Nadal's career replicated in miniature.

Sometimes a single game, or even a single point seemed to sum it up, making clear once again the irrefragable, the bleeding obvious truth about Nadal.

He played the first set in a fit of overwhelming brilliance. But there is a problem with playing out of your skin: it doesn't last for ever and when it stops, you are at your most vulnerable. There are very few players capable of understanding that in the blood and thunder of a match, but Nadal is exceptional.

Djokovic came back. He broke Nadal by winning a heart-breaker of a rally that lasted 54 impossible strokes, took the set and went rampaging into the third, breaking in the first game. Nadal went on to break back, but then Djokovic was still on top and held three break points against him. It seemed the match had swung decisively.

If you've been paying attention, you will be aware that Nadal didn't hold that view. No, he didn't give up. He got to deuce with a rare ace, the only one he hit in the entire match, not a bad moment to bring it out. He held and then he broke and Djokovic's spirit broke at the same time. The last set was a bravura display of dominance.

There is more than mere tenacity to Nadal's game of course, but that is always the most obvious part of it. Sport is supposed to reveal character, so we really should have realised that tenacity is something that goes beyond ball-chasing. It is the keystone of his nature, the part that supports the entire structure.

We have become accustomed to saying that Federer is the greatest tennis player of all time. Call it blasphemy, but we may be forced to amend that view in a couple of years. But it's only Nadal: feel free to write him off.

The Times