French senate absolves Froome while laying bare ghosts of 1998

A damning report has shown that 18 cyclists tested positive for EPO in the Tour de France 15 years ago, Owen Slot reports

A damning report has shown that 18 cyclists tested positive for EPO in the Tour de France 15 years ago, Owen Slot reports

ALTHOUGH numerous old wounds were reopened, one of the few winners on another painful day for cycling was Chris Froome, victorious in the Tour de France.

The Englishman was given a very significant stamp of approval by an anti-doping commission that has been sending shivers through the sport.

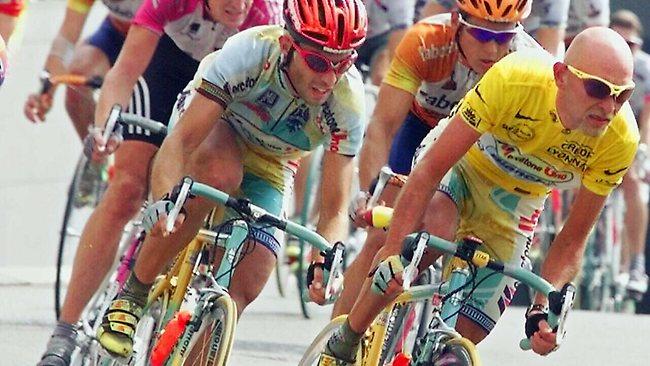

The French Senate yesterday delivered its verdict on an investigation into doping that revealed the names of 18 riders from the 1998 Tour, including the late Marco Pantani, the winner, who had tested positive for EPO in tests that were carried out in 2004, the year that he died.

In making public the findings, Jean-Jacques Lozach, the Commission Secretary, said: "I trust the generation of the current riders, notably the French. We also know that suspicions over Chris Froome's performances in the recent Tour de France are unfounded, not legitimate and not scientifically justified."

One of the French riders who was exposed in the 18, Jacky Durand, also jumped to the defence of the modern peloton, saying: "The next generation must not pay the price for our crap. Today I am not thinking of myself, but of them. My career is in the past. Now I'm thinking of the kid that could be a breakout star during the Tour who has to listen to people say: 'You're drugged up like all the others.' I don't want these cyclists to be discredited just because everyone from my generation was full of bulls***. Our sport is much cleaner now, I want people to understand that."

However, even though we are used to the dark truths of the past being dragged into the present, this rewind to 1998 was clearly painful. The list of 18 was accompanied by another list of 12 who were deemed "suspicious". It has long been accepted that Pantani was a doper, yet this is the first genuine proof. The second-placed rider in 1998, Jan Ullrich, confessed last month to doping, and is shown in the re-tests to have tested positive for EPO twice.

In that 1998 Tour, the yellow jersey was worn by seven different men, and only one of those did not appear in either list - Chris Boardman, the British rider who won the Prologue.

Of the other 21 stages, ten were won by riders listed in the 18, two of them by Mario Cipollini, the adored, charismatic Italian, who was named in February as a client of the infamous doping doctor, Eufemiano Fuentes.

"Cipo" felt so unsullied by the Fuentes revelations that he rode the second stage of this year's Tour before the race with his shirt off and his hair slicked back, apparently still very much the star. After the revelations, he may feel different.

However, as the riders of old reel with the blows, an acceptance appears to have set in among the public that doping was so widespread, it was the norm. News that the name of Laurent Jalabert, one of the most loved French riders, was to appear on the list of 18 had spilt into the media before the 2013 Tour started in Corsica, and yet, on every stage of the race, "Jaja" was painted on the roads as a sign of his enduring popularity.

Not every rider, though, can just dismiss the past. The fourteenth stage of that 1998 Tour was won by Stuart O'Grady, the Australian, who retired on Monday having just completed a record-equalling seventeenth Tour de France.

However, even before O'Grady was named on the "suspicious" list he had confessed to his family thatt he had been part of the dirty past.

O'Grady, an Olympic gold medal-winner, insisted that he had only ever doped once in his life - for that 1998 Tour. He also said that telling his parents in Paris on Monday was "the worst moment of my life".

He said: "I just asked them to listen so I could paint a complete picture. All I've ever wanted in my career was to make Mum and Dad and my family proud. You win the Olympics, Paris-Roubaix and now all of that is going to be tainted by this action and I wish it could be changed but it can't.

"I want to paint a picture why I chose this avenue and make people understand how different things were and how isolated I felt. It wasn't systematic doping, I wasn't trying to deceive people, I was trying to survive."

With the release of its report yesterday, the Senate stipulated that there would be no official repercussions, no results would be stripped. The samples themselves were taken in 1998, stored and then tested in 2004 when a test for EPO had become available. As those samples have since been destroyed, there is no opportunity for the named riders to mount any kind of defence.

That is one reason why the CPA, the professional riders' association, spoke out last week against the releasing of names. Nevertheless, the picking over the bones of the past will continue.

Jonathan Vaughters, the Garmin boss and former rider, went on Twitter to denounce the list of names as "meaningless" because not all of that year's peloton were tested. He then claimed that if the entire peloton from 1998 had been tested three or four days before the start, then every rider would have been positive.

Presuming that there were at least a few who were clean, that is a comment that is unlikely to have gone down well.

The Times