Dehumanised, dispossessed – who considered Imane Khelif’s life beyond boxing?

Does that bring home what has been done? Nobody should be “it”. Pet owners are offended if a beloved dog or cat is called “it”. Yet that’s how Khelif would have returned to Algeria, had a significant number of public voices had their way. As an “it”. Dehumanised, dispossessed. Algeria is not the most free-thinking country in its attitude to gender issues. Homosexuality is a crime and the law does not allow people to change their gender medically, surgically or even on official documentation, such as a passport.

Yet no thought appears to have been given to Khelif’s existence outside the boxing ring. No discussion of how a person might conceivably exist going forward has been inspired by this story. Ironically, Umar Kremlev, president of the disgraced International Boxing Association, did offer psychological support to Khelif should the pressure become too great. This was after he crudely speculated on what was between her legs, wondered whether it could be the result of a sex change and referred to Khelif as a man.

The reason Khelif was raised as female is no doubt she presented as female at birth and, quite probably, continues to do so. If the allegation she suffers from a condition known as DSD (Differences of Sex Development) is correct, she would have looked to the doctors, her parents and anyone else in attendance like a baby girl. Now, she will look like a woman because DSD complications are often internal.

Also, Khelif is from Biban Mesbah, a town in the north-west of the country with a population of roughly 6000. Many of the athletes found to have DSD were born away from the biggest urban centres. Hudson Institute of Medical Research out of Melbourne states around one per cent of babies are born each year with a DSD, where genetic, hormonal or physical sex characteristics (genitals, gonads and chromosomal patterns) are not typically male or female. This makes “it” as commonplace as red hair.

In the United Kingdom, most DSD conditions, such as internal testes, are identified at birth. An endocrinologist or pediatrician detects an absence of clarity, conducts further tests, and then moves forward with either surgery or hormonal treatment, in consultation with the parents – surgery because tumour risks for dysgenetic DSD conditions runs between 15 and 33 per cent, depending on the issue.

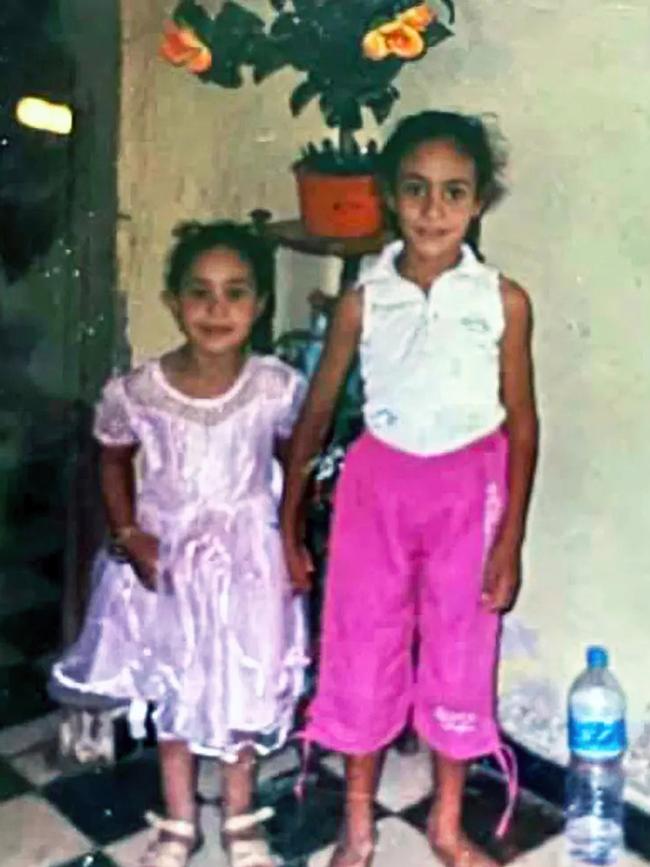

If one imagines Khelif’s upbringing, if a form of DSD was missed – if, indeed, “it” was even allowed to be identified, given Algeria’s adherence to gender norms – then her painful cries of “I am a woman” are understandable. She was raised as the daughter of Amar, a shepherd and blacksmith, and the elder sister of four siblings. There she is, in family photographs, a little girl to the outside world like any other, dressed in pink.

The family was poor, the location isolated. It was a community in which women rarely left the home and not all schools in Algeria are co-educational. Certainly men and women are divided in worship. And Khelif has described Biban Mesbah as a conservative place, hers as a conservative family.

When her sporting attributes became obvious, she had to leave and live with her uncle Rachid in the nearest city, Tiaret, to continue her training, because locals were gossiping about her sessions with a boxing coach, who was based ten kilometres away. Why was she allowed to travel alone? And this is the environment into which she would have been forced to return, humiliatingly branded neither one thing, nor the other. Not a boy, not a girl, just an “it”. Where do “its” sit in a mosque? Where do “its” change in a gym? Few seemed to care.

It wasn’t so long ago that one of the defining questions in the run-up to the general election was “can a woman have a penis?” And the only right answer it seemed was no, no, no, no, NO! And for the most part, we get that. Yet fast-forward a few months, consider what we think we know of Khelif, fellow boxer Lin Yu-ting, the runner Caster Semenya and others, and contemplate whether a man can have a vagina? Apparently, the answer is now yes, yes, yes, yes, YES!

Yet it is hideously cruel to refer to Khelif by male pronouns or to accuse her, as some have, of being a calculating person, a man who enjoys punching females. It would be impossible for her to change gender in Algeria, even if the presence of XY chromosomes allegedly detected by IBA testing were confirmed. It would be impossible for her to live her life in her country as anything other than a woman. This is an entirely different issue to fairness in women’s sport, because the responsibility of any authority does not end when an athlete climbs through the ropes or leaves the arena.

We heard a lot about mortal danger in Paris, yet nobody dallied greatly on the mental wellbeing of a competitor arriving a woman and denounced as a man. A punch hurts, but it is not necessarily the worst thing that can happen to a boxer if sport does not handle this issue with care. Yet once boxing in Paris was subject to the International Olympic Committee’s contestable rules around inclusion, the challenge was not to make a bad situation worse - and that did not happen. Lord Coe, the obvious successor to the IOC president, Thomas Bach, suggested boxing became a mess because the IOC did not have rules, but that is not true. It did have rules; just not rules with which anyone agreed.

Yet why was the IOC even in charge of boxing? Because boxing was bent. Under the auspices of the IBA - previously the AIBA - outcomes were routinely the result of bribes or direction. All 36 judges and referees from the 2016 Olympics were banned from officiating in Tokyo. Yet these are the good guys, apparently, because of sex tests conducted in 2022. That it took a year before those tests were repeated is just one of the many mysteries about the conduct of the Russian-controlled IBA. Maybe they were too distracted with banning Ukrainian fighters. Still, as long as you’re on the same side of the argument as Donald Trump, Elon Musk and Piers Morgan, what could possibly go wrong?

Sadly, it created a perfect storm, of division, corruption, complacency and circumstance that could have ended up with an athlete getting seriously hurt or damaged, and not necessarily in the way imagined. Sex testing is possible in women’s sport and, given what has unfolded, preferable, too. Yet it must start earlier, with clearer guidelines for controls and outcomes, and greater understanding of what the results may represent for individuals, and the duty of care that follows. That did not happen in Khelif’s case. In the court of public opinion, she was cast out of the XX club, with no appreciation she had nowhere else to go.

So it’s complicated. Yet here was a teachable moment about the complexities of modern sports governance that instead forgot the humans in the middle, and all because too many observers thought they were “it”.

The Times

Writing about Imane Khelif, the boxer, is difficult. Not in what to think, but what to say. Specifically, the pronouns. Refer to Khelif as “she” and there may be outrage. To refer to Khelif as “he” risks denying a lived experience and that of parents, siblings, friends, educators and imams. So let’s call her what the various Sexfinder Generals have made her. Let’s call her “it”.