‘Inside, I was dying’: Jelena Dokic on her father, his abuse and her emotional torment

The first interview I did with tennis star Jelena Dokic resulted in her father threatening to kill people with his grenade launcher. This is the story of how I ended up writing her memoir and co-directing a documentary on her life.

On a warm autumn morning 15 years ago I woke up to the news that “tennis dad from hell” Damir Dokic was threatening to kill people with his grenade launcher.

It was in response to a story I had written with his estranged daughter, former world No.4, Jelena Dokic. She had confirmed to me in a lengthy interview she had been physically abused by her father.

“I’ve been through a lot worse than anybody on the tour. I can say that with confidence,” Jelena told me.

The story caught fire across the world and while Damir confirmed he had indeed physically abused Jelena, he was furiously unhinged. He made telephone threats to kill Clare Birgin – Australia’s then-ambassador to Serbia – and was found with a cache of weapons, including hunting rifles, Berretta pistols, two bombs and 20 bullets. Damir was jailed.

It was a catastrophic outcome for everyone. Jelena was filmed overcome with tears as she tried to prepare for the French Open.

Seven years later I would end up ghostwriting Jelena’s bestseller memoir and that now has led me to co-direct a documentary on her life, Unbreakable: The Jelena Dokic Story, which Roadshow Films is now distributing in cinemas. It has its world premiere at the Brisbane International Film Festival on Sunday.

While Jelena is now a firm friend, an unofficial younger sister in a way, there was a long time when she didn’t trust anyone…including me. And she had every right not to trust me, because for the first 33 years of her life, rarely any outsider had stepped in to protect her when the times were really brutally hard and horrendous.

BEATINGS

It is more than two decades ago now, but I vividly remember being a young journalist in newsroom and later at tennis tournaments, hearing senior writers and tennis identities tell a story about Jelena being “thrown around in a hotel room” by her father.

“I know people who were in the next-door hotel room after she lost matches and he used to beat the shit out of her,“ was what one tennis legend often told journalists.

There was also the “rumour” Damir was so angry with her that he made her sleep at the Wimbledon clubrooms one night and she was found curled up in the players lounge by a cleaner.

It’s not a sad, gross overestimation that by the early 2000s “everyone in the tennis world” knew Jelena was being abused – or at the very least everyone knew something was horribly wrong within that family unit. It was a deranged open secret of sorts.

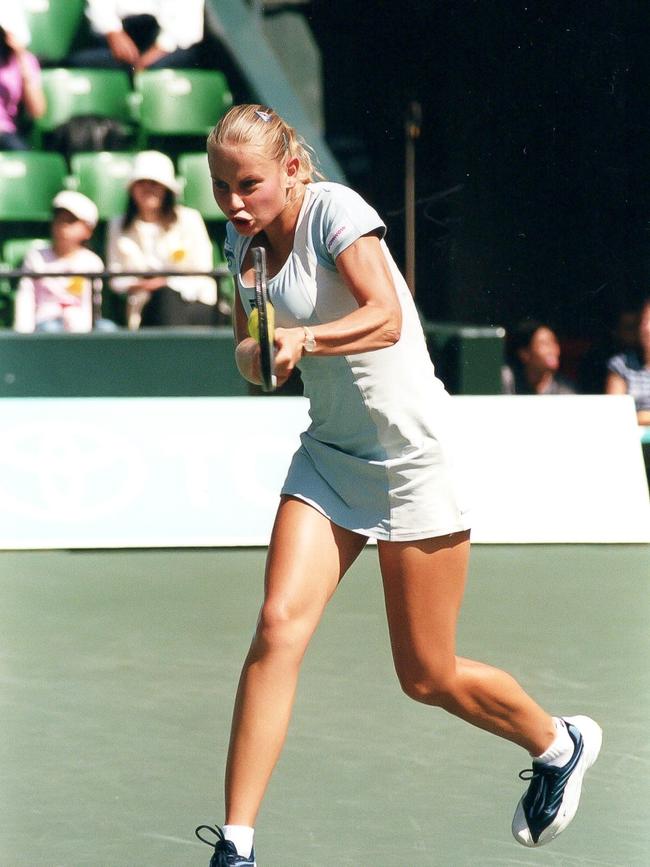

But Jelena was our greatest hope since Evonne Goolagong Cawley and so some people turned a blind eye as she rocketed up the tennis rankings all the while her father was causing horrific chaos. He was arrested at tournaments, often drunk, and was famously being booted out of the 2000 US Open after he fought with a waitress about the price of salmon. In return he was lampooned in the press and he even made money out of it, securing a contract to do a host of TV adverts. It was wild. Meanwhile, behind closed doors, Jelena was, just, surviving an onslaught of abuse.

Jelena would drop off Australia’s radar around 2003, at 19 she “fled” the family home, she then drifted in and out of the tennis tour. But by January 2009 she was on a glorious comeback and made the Australian Open quarter-finals that year in electrifying style.

Since those early news room conversations, I had wanted to tell her story. Through many negotiations with her management company she agreed to an interview.

In April 2009 I flew to Miami. After a glamorous photo shoot with then Fairfax’ s Sport&Style magazine, we sat down with her in an empty hotel room bar and I had the opportunity to ask her the question; people had seen bruises on her skin in the locker room, the rumours were her father had abused her, was this true?

Jelena confirmed it, but did not elaborate, but to say she had suffered worse than anyone could have imagined. After the interview ended, I stood up and Jelena in her firm way turned to me and said: “I will write a book one day”. But that was by no means, “I want you to write my book”. But it stuck in my head.

I filed the piece. Damir went horribly wild again. His response to the story would see him jailed. After that, all I could think was that I was yet another journalist who, in some way, had ruined Jelena’s life. I had written a story that had made her dad go crazy, again. I thought Jelena would hate me for it.

‘GOT IT’

It was about seven years on from that interview, I took a phone call out of the blue from Jelena’s manager, David Malina. Jelena had been three years retired by this point.

“Jelena Dokic wants to write a book, can you do that?” David asked simply.

I immediately said ‘yes’. I wrote up a book proposal and emailed it out. From memory it was rejected four times. One publisher, who truly understood Jelena’s story, couldn’t convince others at their acquisition meeting.

The rejection letter read: “I sold it hard but the table was pretty adamant, a) Jelena’s story, while worthy, was too sad and tawdry to make widespread reading; b) no one wanted to spend any extended period revisiting the hijinks of Damir; c) Jelena’s dual nationality diluted her patriotic appeal; d) the events of her life happened too long ago”.

Only Penguin Random House’s Alison Urquhart “got it” and agreed to publish the memoir.

So years on after interviewing Jelena in an empty hotel bar in Miami, I met with her again on a Saturday morning at her apartment complex in Melbourne in October 2016. With her tennis career long over, she was struggling with her fitness and health. Her breathing was laboured as we walked from the apartment foyer to a lift up to a meeting space that overlooked the city skyline.

She was quiet, her eyes downcast, and she dryly started to walk me through a few early parts of her life. Jelena gave scant details. She coldly confirmed stories here and there – “yes my father abused me…he hit me a few times” – but then didn’t go into any more than that on the first day.

But somehow, slowly over the next 10 days she opened up. The more she spoke, the more trauma she remembered. Listening to her was a privilege and horrifying.

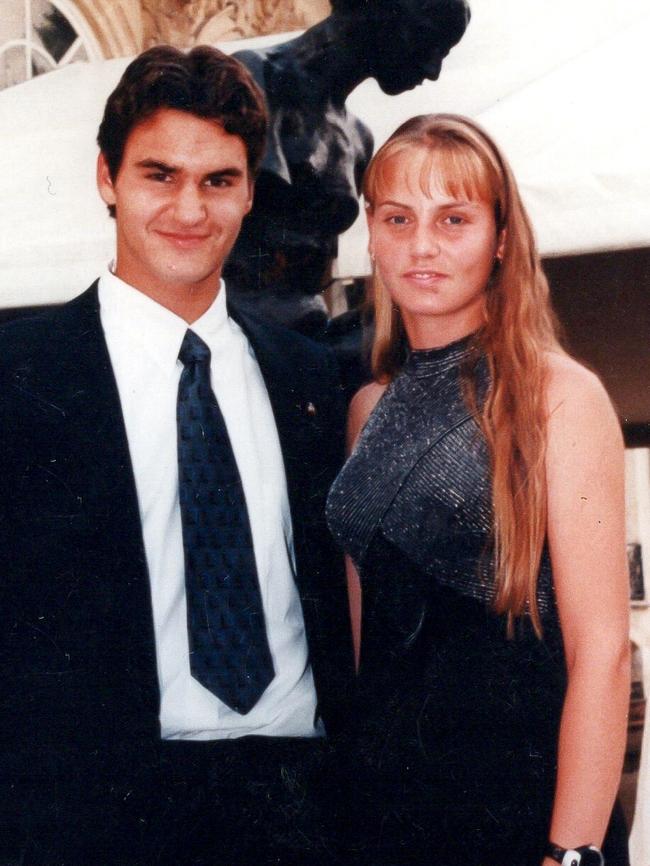

There are only two times Jelena cried in the interview process. The first was when she recalled being banished by her father and told she couldn’t come home after she lost to Lindsay Davenport in the semi-finals at Wimbledon in 1999.

The second time was while telling me the story of the shame and embarrassment she was made to feel when her father made her switch nationalities and was booed on the Australian Open centre court in 2001.

She in no way broke down telling me those stories – she just had tears gently rolling down her face as she unpacked it all. She spoke of shame and rejection. I tentatively hugged her at the end of these sessions. Jelena barely hugged me back.

When I asked her about this recently, this steely resolve around recounting the horror show of her youth, Jelena explained it: “I had buried that pain so deep, I couldn’t trust anyone, even though I was telling you my story, that pain was cemented so hard deep inside, you block and block it and for most of my life I found vulnerability was something to be ashamed of.”

Other experiences were methodically, calmly unpacked. Like the time her father knocked her out cold in a hotel room in Canada; or how he would make her strip down to her sports bra and face a corner of the room for hours on end as punishment.

But while slightly unburdened by telling “her story” – her mood lifted through the process – she was also suffering post-traumatic stress disorder. I recall during the editing process she called me in a panic. “Hey, I think I need to speak to someone…I always feel like I am being stalked and that there are people coming to kill me.”

She was fearful of crowds. Of people. Again. She still really trusted no one.

As we finished off the manuscript over six months, she often wondered out loud: “Do you think anyone will read this book? Will people care?”

She says November 13, 2017, is the day that changed her life. An extract from her new book appeared on the front page of the News Corp Sunday tabloids. People were floored by her story – and people cared for it. Her story led TV news bulletins that night.

She called me while watching footage on the news of Damir going wild at the 2001 US Open and fighting with security. “He was really crazy,” Jelena said, almost in disbelief. “It was really bad, wasn’t it?”

While the written word was powerful, it was clear the archival vision, well handled, could be explosive and impactful and with that a movie had to be made.

TRACTION

While it took some time and obstacles for Jelena’s story to be published, the “Unbreakable” instantly became a best seller. The documentary too would take some time to find traction. It was optioned then fell over at a production company.

It was eventually Ivan O’Mahoney (In Films) who optioned the book and made the film. Much like trying to get her memoir published, it was a battle to get this documentary off the ground.

“Despite the success of the book, it was still hard to get the film made,” O’Mahoney says. ‘Some broadcasters thought it wouldn’t appeal to a broad-enough audience, others seemed paralysed in their decision making. We had a real breakthrough when we presented the project to Edwina Waddy and Joel Pearlman at Roadshow Films. They just got it. They saw both its appeal and its importance.’’

In fact, Roadshow believed in the project so much, they acquired the worldwide distribution rights. It was a seal of approval that would propel the project forward.

Ivan and I saw the film as an opportunity to do something different. The book is written in Jelena’s voice, but in the film we wanted to juxtapose how Jelena saw the world with how the world had seen Jelena and her dad. We figured with the benefit of hindsight, some real lessons about (the lack of) safeguarding could be learned from seeing those perspectives side by side.”

The film took several years to make. One of the reasons for that was this was not an easy subject for people to talk about, nor want to be associated with, and securing access to interviewees who had witnessed Jelena’s story first-hand was an arduous process.

Eventually, a number of high-profile people agreed to go on camera, including former tennis writer at the New York Times Christopher Clarey, CBS 60 Minutes reporter Jon Wertheim and tennis champions Lindsay Davenport and Pam Shriver. Others hid and shirked the chance to front up.

While Jelena says the doco interview process was “tough”, it’s rewatching her life story that has been the hardest. “Watching the footage of him going crazy, the archive footage, it was very hard emotionally,” she says.

She is always moved by Davenport’s empathy and former WTA CEO Bart McGuire’s observation she looked like she was “in a hostage video” when she was giving outlandish statements to the media (always scripted by her father).

“Inside I was f--king dying,” she says.

The other day as we texted about the film’s imminent release, she wrote: “You did not give up on the truth and me that’s why all this is happening…I would not have told my story without your support and belief in me”.

While it’s an honour to have Jelena trust me now, it’s all her strength and courage that has led to arguably one of the most important sports stories being told. She has become a much adored role model who’s mission is to change people’s lives by telling her story.

“But I don’t want people to see me as a victim,” Jelena says. “I want me them to see me as as success story.”

‘Unbreakable: The Jelena Dokic story’ is in cinemas from November 7.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout