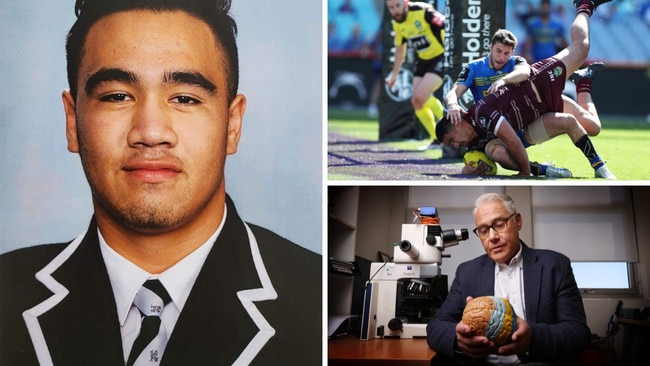

Keith Titmuss was suffering CTE when the NRL rookie died at 20

Keith Titmuss is the youngest Australian sport player to be diagnosed with the fatal condition related to repeated head knocks.

Rugby league rookie Keith Titmuss had the brain disease Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy when he died aged 20 – the youngest Australian sport player to be diagnosed with the fatal condition related to repeated head knocks.

The diagnosis – made after Titmuss died of exertional heat stroke following a 2020 Manly Sea Eagles training session and until now not disclosed – has sparked warnings the major football codes are not doing enough to protect young athletes.

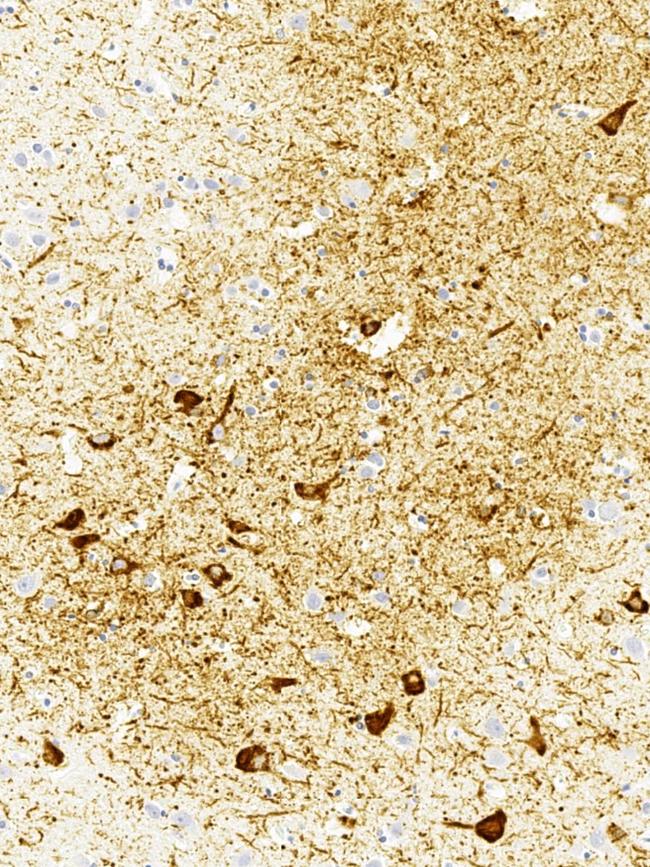

Neuropathologist Michael Buckland was stunned to find stage two CTE in Titmuss’s brain. He declared the finding should be a “wake-up call” to parents, and was further evidence that sporting codes needed to strengthen concussion protocols and reduce contact in training. Dr Buckland said Titmuss, who had played rugby league from age five and was a gifted schoolboy rugby union player at Newington College in Sydney, had had a substantial exposure to repeated head impacts throughout his 15 years playing junior contact sport.

Unlike senior rugby league players including Wally Lewis, Paul Green and Mario Fenech, Titmuss developed a brain injury without ever pulling on a jumper at the highest level.

“Keith’s brain is showing us that, at least in some cases, CTE actually starts during a person’s playing career and starts very young,” Dr Buckland said.

“I wasn’t really expecting to see CTE because of his age.

“What this finding tells us is that it doesn’t matter how good your concussion management is, or if you don’t even get a concussion, it’s that large exposure to repeated impacts, many of which will be non-concussive, are still doing subtle damage to the brain that causes CTE.”

The Titmuss family issued a statement to The Weekend Australian, saying that, while CTE could be a “taboo topic”, the codes needed to do more about reducing hits to the head.

Titmuss’s parents Lafo and Paul said they had never seen their son “majorly concussed”. However they did see him “receive many blows to the head and head jerk movements throughout his footy career”.

Titmuss’ death was the subject of a coronial inquest earlier this year, which found his cause of death was exertional heat stroke. It criticised Manly’s “inappropriate and unsafe” training methods and called for better policies to protect footballers.

Following the CTE finding, the Titmuss family are again calling for a safer training environment.

“This may lead to changing the rules of sports and, therefore, affect our enjoyment of sports entertainment that we love,” Mr and Ms Titmuss said.

“However, the rules of the game should continuously evolve to prevent injury to our sportspeople. Death of nerve cells in the brain is a serious matter for our community to think about and talk about. We may need tighter safety measures and rules for all sports to protect our sportspeople’s brains and enrich their quality of life after sport.

“Dr Michael Buckland’s research is crucial, and his findings must be acknowledged by all sports codes that have experienced incidents involving head injuries. For example, a boxer wearing headgears serves to prevent cuts, scrapes and swelling but not concussion. This is why we urge all sporting governing bodies to take up the responsibility of continuously reviewing their head injury rules and prevention measures for an individual sports person’s quality of life.”

No warning signs

The Titmuss family said their football-loving son hadn’t show any “red flags” of CTE.

“Keithy’s personality, nature, and behaviour never changed,” the Titmusses said. “He was witty and a deep thinker. His siblings disliked bantering with him because his responses were funny and irrefutably true”.

Dr Buckland said that while other athletes might show signs of the disease at stage two, it was clear from Titmuss’s parents he was yet to show symptoms.

“From American football players, most of them with stage two disease do experience some signs and symptoms, but in this case, it’s been clear that Keith hadn’t displayed any of those,” Dr Buckland said. “We know that there is a pre-symptomatic phase of the disease where the pathology is starting to develop before it declares itself … (but) certainly in Keith’s case, we would have no idea if, the signs of symptoms would come on in the next year or in five years, 10 years …”

Dr Buckland said Titmuss’s case demonstrated that young people playing contact sport were at risk of CTE.

“He had early exposure and he had a lot of exposure and I think every parent should sit up and consider their child’s long-term brain health and ask the question of the codes: are they doing enough?” Dr Buckland said.

“We know there are lots of positive benefits about participating in sport, and we don’t want to take any of those away. But we need to be really, really careful and really aware of any head knocks that occur and making sure that your child is not exposed to multiple head knocks over a season.”

Dr Buckland said the codes should reduce contact training as this would significantly reduce a player’s exposure to non-concussive brain injuries.

The Australian Sports Brain Bank has found CTE in the donated brains of 48 of 99 sportspeople since 2018. Twenty played Australian football, 13 at the professional level. There were 16 cases in rugby league; eleven of those played professionally. And six played rugby union, of whom two were elite players. Another four CTE cases have been uncovered as part of the NRL’s Former Elite Level Athlete program.

CTE caused a revolution in the US, raising awareness that repetitive hits to the head can lead to cognitive problems. This has sparked reforms including a reduction in contact training in professional American football and legislative debate in California about whether young tackle football should be banned.

Currently there is no restriction on contact in training at the elite or grassroots level of either the AFL or the NRL. Roosters player Luke Keary, who has had a history of concussion, has questioned why the NRL has not yet implemented a policy that policed contact in training like the NFL. The Rugby League Players Association has also called on the NRL to address this.

This year the Victorian coroner accepted expert evidence that exposure to repeated hits to the head was correlated with CTE and recommended the AFL take steps to reduce contact training.

The AFL, which is currently investing $1bn over the next decade to attract young players to the game, said it was examining this recommendation but has yet to make this change.

Dr Buckland said all codes should be on notice following the Titmuss finding. “It’s particularly concerning given that there’s a large amount of money being invested in recruiting young people to these games and Keith lived a healthy life,” he said. “There was no drug or alcohol abuse. He played a lot of his career under modern concussion guidelines … yet all those safeguards were not enough to stop him from getting this brain disease.”

Model footballer

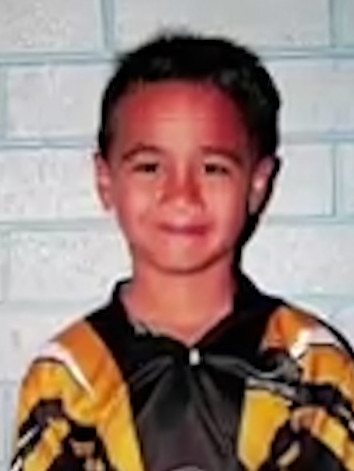

Lafo Titmuss has described her son as “unassuming, honest, kind, respectful” and a person who was “loved by so many”. He was also, clearly, a brilliant athlete.

Such were Titmuss’s football talents he was in high demand as a teenager and in 2017 and 2018 he played rugby union for Newington and rugby league for the Manly Sea Eagles juniors. He was a dedicated trainer in both codes.

Twice a week he would rise at 5am to attend training at Newington by 7am. After school Titmuss then trained for nearly another two hours before he was picked up by his Manly coach and taken to the Sea Eagles facility in Narrabeen for more training until 7.30pm. Afterwards a Manly minibus drove the young recruits back to Hoxton Park in Sydney’s west so he could get home by 9pm, finish his homework and then fall asleep by midnight.

Mr and Ms Titmuss recall these bus rides back from training were a highlight for their son.

“We’ve heard many funny stories about Keith from his footy mates during these bus trips,” they said. “One was, during their trips back to Hoxton Park in the minibus, Keithy would usually be in the back of the bus, legs stretched out, asking the boys to take off his footy boots and massage his feet – while he had his school laptop open, doing his homework. And, of course, the music selections for the trip were from his phone. We love that these boys loved him that much.”

Hidden toll

Australia has nearly a million grassroots athletes and professionals taking part in football across all contact codes.

Dr Buckland said it was not yet possible to say how many were at risk of CTE or cognitive problems.

In response to a series of detailed questions, the NRL issued a six line statement reiterating the code was “committed to players at all levels of the game, particularly in respect to head trauma and concussion”. “The NRL has one of the most comprehensive head-injury policies and procedures in sport”, it said, based on “conclusive data”.

The league would “continue to invest in research and review its policies”. The NRL statement did not mention Titmuss’s CTE diagnosis.

Dr Buckland said making Titmuss’s diagnosis public was “hugely important”.

“Out of this terrible tragedy, this is a significant legacy of Keith’s,” he said. “I really think what we’ve learned from Keith’s brain that will help others and will save lives in the future, it’s clear that we need more action to prevent this terrible disease.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout