Parents recount the final moments of NRL player Keith Titmuss

Ahead of a coronial finding into the death of their footballer son Keith during a training session, Lafo and Paul Titmuss recount his final moments and hope for answers that will spare others their pain.

Not long after the gruelling 2020 Covid lockdown, Lafo Titmuss and her husband, Paul, are at their Sydney home when the call comes through that their boy, Keithy, is not in a good way.

“I took the initial phone call at around 10am to say something had happened with Keith, and to ask us if we could come down to the grounds at Narrabeen,” Paul says as we sit chatting at their kitchen table on the southwestern outskirts of Sydney this week.

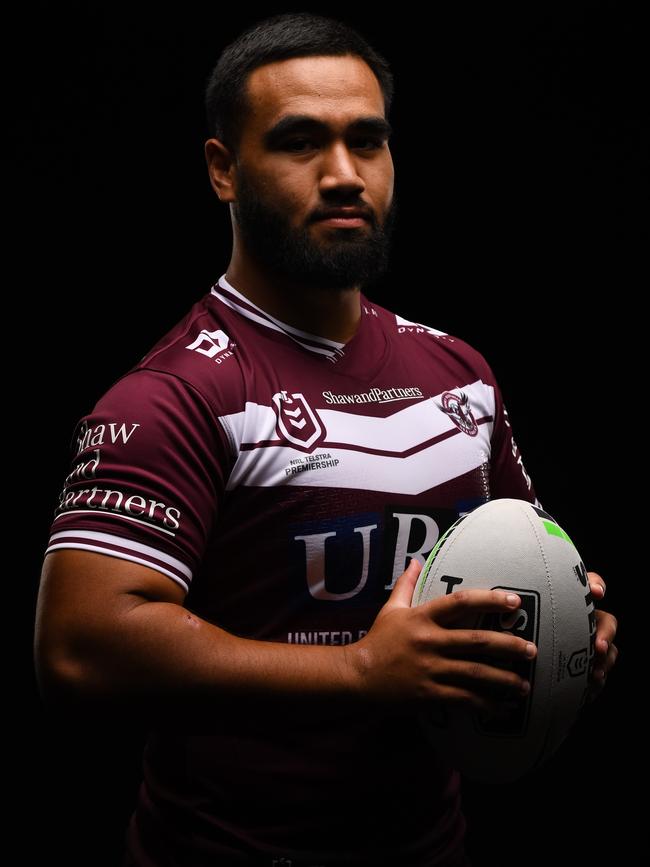

The room is decorated with large photos of a muscular Keith in his Manly jersey.

In November 2020, Keith Titmuss, 20, a rising star, had just been promoted into Manly’s top-30 squad for the 2021 season. He’d made it into the big time.

He’d been enticed to sign with the club at 14 when one of the game’s greatest players, Bob Fulton, sat at the kitchen table with Lafo and Paul and outlined his vision for their son’s grand future.

On that November morning in 2020, Fulton’s dream became Keith Titmuss’s reality as he excitedly made his way up to the Sea Eagles’ training facilities on the northern beaches, a 75-minute drive across the city, for his first run in the top squad in the team’s first training of the season.

“At the time, I didn’t think it was serious or anything like that,” Paul Titmuss says of the call from the club that morning. “Lafo wasn’t going to come with me but she decided she would.”

Lafo chimes in: “It was kind of a hectic day.” A small silver K dangles on a chain around her neck and she rubs it often for comfort.

They hop in the car for the drive across the city to their son and with each subsequent phone call their anxiety is squeezed a notch. The first call to Paul is from a trainer who is in the back of the ambulance with Keith.

“He said: ‘Make your way over to the Northern Beaches Hospital.’ I asked him if it was serious and he said ‘Yes mate, it is’.”

“Then we get another phone call: ‘Paul, you’ve got to go to Royal North Shore (ICU).’

“So now we are thinking something bad is happening.”

Lafo says they knew it was bad but thought it recoverable-bad. “We weren’t so concerned because Keithy was the strongest, healthiest child of the three of them,” she says.

As soon as they arrive at RNSH, the optimism they’ve been clinging to is ripped from them. “As we approached the counter, the hospital staff is waiting for us,” Lafo says. “They ushered us quickly into a family room where Des and (Manly trainer) Matt Ballin and a social worker were waiting … the manager of the ICU came in and explained that Keith was very unwell … we were thinking he’s very unwell but that we would see him in a couple of hours. At no time did they say he may not pull through.”

Des is Des Hasler, the then Manly coach, who remains by their side.

“My memory is they said they were giving his heart and lungs a rest and they were putting him on a life-support machine,” Lafo says, while they ran some tests.

“But they didn’t say he might die. If they did, I’d have fallen to my knees. I’d be praying. I’d be calling my family, my community to say ‘Drop to your knees … start praying for my child’

“I wish we had been given an opportunity to see him while he was still alive …”

At this point, Keith’s older brother Jesse and younger sister Zara arrive at the hospital. “When they broke the news that he was gone, we were all in the room together,” Paul says. “I think it was just the two of us, with Des,” says Lafo, gently correcting him.

“So we asked the ICU manager to bring Jesse and Zara into the room so we could tell them. We did a little prayer and we asked if we could see Keith.”

It took a while to get in because the hospital staff insisted they needed to clean him up and remove the tubes. “I was thinking I don’t care what you need to do, I need to see him,” says Lafo.

When they were let in, “I just couldn’t believe it, just to see him lying there,” his mother says.

“He was still warm. I held his hand and wouldn’t let go. I just wanted that warmth.”

Paul says: “We had always protected Keith, but he was becoming his own man. And so we trusted (the Manly club) to do the right thing. You go to work, you don’t expect to die at work … the thing that was going through our minds was, did they push him too hard?”

On Friday, NSW Deputy State Coroner Derek Lee will try to answer that question when he hands down his findings into the 2020 death of Keith Titmuss.

Was it irresponsible, even reckless, to put the players through such an arduous session in the heat on their first training of the season?

Will it herald the implementation of heat policies for rugby league and other sports?

Just how far is acceptable for clubs to push their athletes, and who is responsible when they push too far?

It also plays into a larger narrative about the treatment in the NRL of Pacific players, who make up almost half the players, and almost none of the coaches, support staff, managers and executives. Do they have a voice?

It’s a brutal sport and anyone who signs an NRL contract knows they’ll face a fierce reckoning on the training paddock – but where is that line between pushing players to the physical and mental extremes, and what is too far? When does tough love become bullying?

The old timers say suck it up princess; the courts may have a different view.

Young Maori player Jackson Topine last week launched a $4m claim for compensation against the Canterbury Bulldogs, alleging that a 2023 wrestling “punishment” was an assault that left him so humiliated and traumatised he can no longer play the game he loved. Earlier this week, the Maori-Samoan player Lloyd Perrett, a former prop with Manly, announced he too was taking legal action against the club after suffering a life-threatening seizure during a water-deprived training session in 2017. He was rushed to hospital unconscious.

“When I heard Keith (Titmuss) died from heatstroke, I cried like a baby,” Perrett said.

The broader question being asked now is do the administrators who control rugby league clubs have a deep understanding of their young Pacifics players, and why aren’t there more officials of Pacific heritage in positions of real power in clubs? It’s an issue that has confronted and confounded US professional leagues, such as the NFL and NBA, over the past few decades. It’s an issue the NRL must now confront.

Grace and power

Paul and Lafo’s lovely new double-story house at Austral is home to four generations – Paul’s mother, their son Jesse and his wife and their two kids, and their daughter Zara. It’s also become a shrine to Keith, with his medals on the sideboard and framed photos of him with a football around the room.

Paul works for Sydney Council and Lafo for Homes NSW. They’re hardworking, Christian people with big ambitions for their kids. They’re “proud, fair dinkum Aussies” of Samoan heritage.

Jesse had played for Parramatta and when that didn’t work out, he went to university. The same would have been expected of Keith. Except Keith is gone, and they honour him on the walls and on the sideboard.

He’s constantly on their minds, Lafo says: “We have to stop ourselves thinking what life would be with him, because that’s too painful. But we are trying to live our best lives in his honour.”

They want to create a legacy for Keith. They’re pushing for change in the sport he loved, the game that took him from them.

Both Paul and Lafo have bravely sat through days of coronial hearings delving into Keith’s final moments. They’ve heard the graphic details of his screams as he went into seizure and his body bounced around the wrestling dojo. They’ve listened to stories of terrified teammates who watched on in horror.

They learned that his best mate, Josh Schuster – a kid they’d known since kindergarten and who was always sleeping over – held Keithy’s hand as he convulsed.

They were told that when ambulance officers walked into the heat of the dojo, they were aghast when their thermometer revealed the kid’s temperature was raging at 41.9C.

Then Lafo took the stand to make a statement for the family. Delivered with great grace and power, it was a testimony to her beautiful son, Keithy, gone too soon. Coroner Derek Lee choked with emotion as the rest of the room wiped away tears.

Paul and Lafo have decided to talk to The Australian to push their agenda of creating a safer environment for young footballers. They don’t want other parents to be seated in a coroner’s court listening to a methodical account of the events leading to the death of their son or daughter. They want to spare others their pain.

During the inquest, Lafo and Paul sat quietly, heads bowed at times, as they heard of the failures that led to Keith’s death.

On the fifth day of the inquest, they heard how in 2018 – following former Lloyd Perrett’s collapse at Manly training in 2017 – Luke Inman sent a warning email to the club’s sports science staff that a portable Kestrel device, which measures temperature and humidity, should be used at every session.

“You are leaving yourself and the club open to litigation if a player suffers heat stroke, or at worst, dies,” wrote the doctor in an email to Hasler and his coaching staff.

Two years later, Keith Titmuss died. There was no Kestrel there that day. Lafo and Paul listened as Hasler stood on the stand and said he couldn’t recall receiving the email from Inman.

Many other issues were raised. The intensity of training, the NRL’s lack of an exertional heat policy, and whether players felt they could speak up if something was dangerously wrong.

The inquest heard of a “warrior mentality” at Manly that encouraged players to push themselves to the limit, never admit weakness.

Some of those same issues surrounding player welfare are in the spotlight with former Australian schoolboys’ captain Topine’s lawsuit against the Bulldogs and in the case of Perrett, who alleges he was forced to go on a punishing run with his Manly teammates in 2017 without adequate hydration.

“We weren’t allowed any water and told ‘If you don’t like it, you can take your keys to the field and go home’.” He was stretchered from the field unconscious and rolled into an ambulance.

“I thought I was going to die,” he says.

At the inquest into Keith Titmuss’s death, Schuster told the coroner that that day at training was the “hottest he’s ever been” but he feared it would be held against him and Keith if they didn’t finish the session.

Schuster was asked by counsel assisting the coroner, Adam Casseldon SC, if players felt able to put their hands up and take a break if they felt fatigued. “Not with Des as our coach,” he said.

Teammate Sione Fainu said there was an opportunity to take a break if players felt unwell, but none dared do so. Fainu said he saw his mate Keith struggling throughout the drills, but said it wasn’t unusual because “everyone was struggling”.

Instead, the Manly pack encouraged each other to keep going. “We had to get through, push through. Everyone was pushing Keith,” Fainu told police.

The players’ accounts were in stark contrast to Hasler’s claim that the training was not an “overly strenuous or taxing session”.

Over the course of the inquest, it was revealed Titmuss had completed two hours and 19 minutes of training outdoors – where he covered 6.7 km – before moving into a “shed” to do at least 10 minutes of highly intensive cardio exercise, which included burpies and wrestling. While Keith never gave up – his body collapsed as he overheated. He effectively boiled to death.

No shortcuts

Keith’s parents are aware of the issues confronting the game. Paul says young Polynesian players are simply unable to voice concerns.

“I think that’s absolutely true, I think they have a fear,” he says.

Lafo adds that Polynesian kids are taught to obey their elders, and from the moment they start playing footy they comply. “It is built in from under sixes – you want to be named for this weekend then you need to make sure you’re at training every day. There’s no shortcuts, which is great, because it’s got to do with integrity … but it’s hard for them to speak up because they don’t want to be considered soft.”

Lafo recounts how Keith never complained about the toughness of training. “Our people, we are about integrity and accountability,” Lafo says. “And so we would probably look down on ourselves if we don’t follow through with what the boss is wanting us to do.

“We’re very loyal and committed. So I’d say with Keithy, he was ticking all the right boxes. He’s not complaining, he’s not whinging.”

His career was founded on hard work. As a teen, he rose at 4.30am to be on time for rugby union training at Newington College, where he was on a scholarship. At the same time, he was playing rugby league with the Sea Eagles. After school, he would make the long trip to the northern beaches on a club minibus with other Polynesian kids from out west.

The Titmusses were also realists – footy couldn’t be everything. “What we’d always say to kids is it’s 70 per cent mental, and 30 per cent your ability,” Lafo says.

They told Keith that if he didn’t feel he could make it, he should tell them so he could apply “for uni courses or TAFE because you need to have a future”.

But he and his mate Schuster had only one goal: to make it in the NRL and play together for Samoa.

He and Schuster had been on the quest since school and while Titmuss was a very good player, Schuster had the makings of a superstar. When he made his debut in September 2020 against the West Tigers, Benji Marshall was astounded: “That’s the best debut I’ve seen from a young kid in my time. Ever.”

Last year Manly re-signed the 21-year-old to an $800,000 a year contract but he was recently cut loose by the club for his poor form.

Lafo says he suffered terribly, witnessing his best friend’s death. “He was very quiet,” she says. “His mum says he would hardly speak to anyone and was always crying.”

She believes the club could have done more, and been more understanding. Instead, Schuster was abused.

Just like Keith Titmuss, Schuster was signed by Fulton as a junior, but after Keith’s death, cracks started to appear – mental and physical. Early in 2023, Schuster took a break to work on injuries and his general fitness but was still in the running to be the club’s long-term solution at five-eighth. However, his work ethic and attitude were being privately, and then very publicly, questioned.

By April last year, as Schuster struggled to recover from a thigh injury, Manly captain Daly Cherry Evans took aim. “If you’re not willing to work hard enough, if you’re not willing to sacrifice, you just don’t last long … He is at a crossroads early in his career but it can be a real positive.”

Kristie Fulton, daughter of Bob and a former Manly pathways manager, attacked him on Facebook a month later. “The solution is simple, he needs to grow up,” she wrote. “Move to Manly, cut ties with the negative influences in his life, stop hanging with fans, control the diet and have the mindset and attitude he once did circa 2019. Too many enablers and excuse-makers around him. It’s always everyone else’s fault.”

It was posted on a Manly fan page with 12,000 members.

Last week, Schuster and Manly parted ways, with the second-rower released from the final three years of his contract. “Josh now needs time to focus on himself and what is best for him moving forward,” Manly CEO Tony Mestrov said in a statement. “We all know Josh is a very talented player and we hope he can find a new club soon. We wish him well.”

Lafo is saddened by the treatment of Schuster and says the inference his family and friends were a bad influence is simply not true. “His family are beautiful people,” she says.

She believes if the clubs are “fair dinkum” about player welfare they need to invest in proper psychological care for players like Schuster.

On Friday morning the corner will deliver his finding. “We sincerely hope the recommendations will be instructive, not just to the NRL but to all sports codes across Australia and worldwide,” Lafo says.