Ron Barassi: footballer and man of the people

From Scrabble marathons to championing women’s football. How Ron Barassi transcended the sport he loved.

Ronald Dale Barassi’s legacy is partly reflected by the shelves of silverware he and his sides won in 10 Australian rules grand finals.

It is one well, but not wholly, represented by the men and women of sport, politics and our national life who have come forward this week to honour the memory of the 87-year-old.

Robert Walls observation that “he was a God to us” was arresting but not surprising, for he was the game’s messiah and at times we were all members of the flock.

It is totally appropriate that he will be granted a public memorial, for Barassi was, as this week has proven, as much a man of the people as he was a man of football.

There’s a saying that you should never meet your idol and it may well be a good general rule of thumb, but in Barassi’s case to meet your idol was to become further captured. Easygoing, charming, quick to laugh, interested, engaged … random encounters left lasting memories among people of all walks of life.

As it did with Shane Warne, the outpouring of emotion and anecdote from the public has added another dimension to the life of a man who was cast in bronze before his allotted time was done.

On the weekend, when the news came through, the women competing in the Sydney Masters AFL competition wore black armbands and paused to remember the time the great Ronald Barassi acted as patron for their 2002 national carnival.

Meredith Gray, a pioneer of football in those parts and veteran of 150 games, told the women present of the impact Barassi made all those years before.

Sydney women’s football was in just its third year and “trying to gain legitimacy”, the then player and volunteer event manager for the 2002 national carnival told The Australian. It was ambitious to try to host the thing and it was in the same spirit that they wrote to Barassi asking if he would fly up for the event.

They’d cobbled together a $500 fee to cover his costs, got a hotel to donate accommodation and Gray offered to pick him up from the airport and drive him around while there. The teams were staying in university accommodation.

They honestly didn’t expect a reply, but Barassi accepted the offer in a heartbeat. Though a man born in the 1930s, he was far from a chauvinist. Just as he believed football should become a national game, he believed it should be played by all sexes.

“Women’s football was the next frontier, we didn’t have to explain it to him, he got it, it was just football,” Gray said. “He stood with us.”

Barassi attended the games, spoke with the players, told them stories and asked them questions. One day while talking with Gray he took a phone call from what was obviously a close friend and while standing in earshot told his mate that these “sheilas go harder than most of the blokes”.

“To know we had the biggest, most iconic name standing by us and letting us know we had his support meant the world,” Gray said.

Women football players were used to the scorn and condescension of the footy world.

Gray played for NSW in the final game against Victoria at Drummoyne in the carnival and remembers being in a bind about how she could get ready for the presentation evening, but Barassi was happy to stop by at her mum’s house while she showered and changed on the way to the venue.

“He was such a lovely man, a great conversationalist and generous of soul,” she said. “He got women’s football before it was fashionable.”

Mum and Barassi apparently got on like a house on fire.

Natalie Morgan, another of pioneer of women’s football in Sydney, remembers the carnival and was playing the master’s game when they stopped to remember Barassi.

“(There’s) a lot of sad women footy players in Sydney today,” she said in a message to The Australian. “He meant a lot to all of us who played back in the early days of NSW women’s footy.”

Barassi waived his fee and went back to his life while female football returned to its long journey toward acceptance.

On 3AW and Gerard Whateley’s SEN radio program so many people from so many walks of life offered stories of their everyday encounters with Ron.

“Greg”, was president of Scrabble Australia in 1988 and had read somewhere that Ron and his wife Cherryl played the game. He invited him to present the prizes at their annual national competition during the Moomba weekend.

Again, he defied expectations and accepted willingly and again he won the room. Again he waived the fee, but his one request was a game against the national champion which was granted.

Barassi got off to a good start. The competitive juices started to flow and the car booked to drive him home was sent away as they pair played on and on.

One of our readers, Brian, responded to last weekend’s obituary with the story of his father writing to Ron and asking him if he would visit his grandmother to mark her 96th birthday.

“On the day he turned up with chocolates and she was absolutely thrilled,” he recalled.

People flooded social media with anecdotes and photos of their encounters with Ron across the decades. “I met Ron …” they begin before the inevitable story of how charmed they were, how much they value the picture, the autograph, the generosity.

“This photo was taken by my son a few years back at an open training day,” Myles O’neil-Shaw wrote. “William even had a couple of kicks with the great man.”

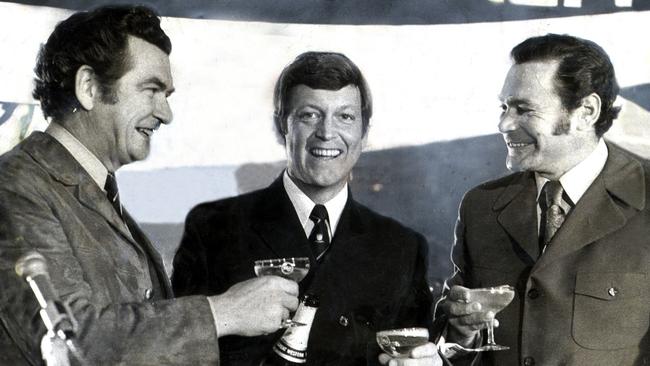

Economist Tim Harcourt chips in with a picture and an anecdote of seeing Barassi at the cricket with Bob Hawke and asking the footballer for his autograph.

“Typical,” huffed the former prime minister. “Little bastard asks for a footballer’s autograph ahead of a politician.”

Perhaps Don Bradman signed more autographs than Ron but it would be a close run thing. The footballer always remembered seeing kids getting Test star Ian Johnson’s autographs at the cricket one day and tearing up one of his mum’s cigarette packets to do the same.

That experience as a boy impressed on him the impact sports stars have on fans and he obliged anyone and everyone when it was his they sought.

Barassi’s story resonates with so many Australians. His presence at the pinnacle of the sport made him a household name, but it was more than just his talent as player or creativity of coach that touched people.

Perhaps it was because his is a story of the game and the country. The Barassis migrated to Australia in the gold rush, a migrant family, they had a vineyard on a dirt track out the back of Guildford which became the family home for generations to follow. Ron’s great-great grandfather Giuseppe was born in northern Italy but migrated in 1854 and had married a Jemima Jarrett who’d given birth to her first child on the banks of the Loddon River. Apparently he was the first white person to be born in the area.

His father Ron headed south to Melbourne to play football but when he was killed at Tobruk the boy spent a lot of time back on the property with his grandfather where he would kick footballs donated by Melbourne alone in the back paddocks when not exploring the bush with his kelpie, Koda (the Australians were fighting at Kokoda at the time).

His grandfather Carlo planted an avenue of trees along the road out of town in honour of Ron who died at Tobruk in 1941, but by the 1950s the Barassis were gone from Schicer Gully Road.

Life moved to Melbourne and the Melbourne football club, he attended Preston Tech, struggled with his new stepfather and moved into a bungalow at the back of Norm Smith’s house when Elza met a Tasmanian and moved to Hobart in 1953.

Smith did not want the boy moved away from the club coterie which had written up a document on the death of Ron snr which said “we declare ourselves the lifelong friends of yourself and your son, Ron, and we advise you that at all times we shall regard the material welfare of yourself and Ron as our sacred duty”.

It is hard to imagine football without Ron Barassi because everywhere you look you see his legacy.