There was only one Ron Barassi but his influence is incalculable

He was already cast in bronze and has always been at the heart of Australian rules football.

A constant in Australian football fans’ lives for the past seven decades, he was a man larger than life and larger than the game – an innovator, a motivator, a person who almost defined what football was and pioneered what it is.

He played it, he coached it, he preached it and he lived it. On the field he was one of the greatest players. Off it he lays claim to being its greatest coach and so much more.

He was so integral to the game and our national identity that in the 1970s academic Ian Turner coined the notion of a Barassi Line, an imaginary divide that split the country into two tribes: those who knew Barassi and those who did not.

He was born of the game and he has died the day after two of the clubs he is most intimately acquainted with, Carlton and Melbourne, fought out a final for the ages at the MCG.

His death will shake the city, the state and the sport. There was only one Ron Barassi but his influence is incalculable. It is fair to say that in the second half of last century football without him would be unimaginable. He embodied and defined it. He was the first-born son who became its prophet. He changed the way it was played and was integral to changing where it was played.

He played in six premierships for Melbourne, he coached Carlton to two, leading the club from the bottom of the ladder to the centre of the Victorian football universe. His call for his side to “handball handball handball” when 44 points down at halftime in the famous 1970 grand final against Collingwood had the same impact on the game that the Beatles had on music. When North Melbourne came begging he accepted the offer, lifting that impoverished club to its first and second premierships. When the Sydney Swans were on their last legs the league convinced Barassi to leave his pub in Melbourne and revive its fortunes, as he had done at the Blues and North.

Barassi did not get the Swans a premiership, but he brought in Tony Lockett and he dragged them from the bottom of the ladder, setting the side on the trajectory toward the success it would achieve in the following decades.

He was everywhere if you were a football fan in the ’50s, ’60s, ’70s, ’80s and ’90s. He was the game’s most famous face, Victoria’s most well-known personality. Kids wore his boots and watched his coaching segments. Adults were treated to his opinion on everything from interstate football to women’s lib. He embraced the television era, he urged the game to evolve with its fans, he walked among them and he was loved by supporters of every single side.

He was filmed apparently walking on water with the Olympic Torch as part of the Sydney 2000 opening ceremony.

Ron Barassi was bigger than any one club.

As a coach he was a Pentecostalist. Beseeching, berating, urging his sides to dig deep and find the sort of spirit that coursed through his veins when he played.

As a man he was endlessly curious, humble and avuncular. He had a smile and a kind word for everyone, he demanded no special treatment. He was oblivious to the respect and stature he’d gained through the game, engaging eagerly with fans in pubs, cafes, restaurants and on the footpath. Someone once said the only person unaware of Ron Barassi’s presence was Ron Barassi. He had no tickets on himself.

To know Ron was an honour and a delight. Hearing I was in St Kilda at a cheap Japanese restaurant with the kids one night, he announced he was joining us to say hello. I protested that it was crowded and we could drop by later and he was, well, Ron Barassi, but he wouldn’t have a bar of it. He wanted to meet the kids and he spent the evening questioning and teasing them as pedestrians stopped on the street outside to point and whisper at the great man’s presence at this most unlikely venue.

Ron took an interest in people and life.

I pull the biography I wrote with him off the shelf and see it was one he endorsed to my daughter who wasn’t sure if she supported Sydney or St Kilda at that point in her life. “Good luck Lucy,” he’s written inside. “Make up your mind between the Saints and the Swans (The Swans!)”

She took his advice.

His signature contained the number 31 from his football jumper and the numbers 17410, which is reminder of the 17 premierships he or sides he coached competed in for 10 victories (it adds up to 31).

Another night he insisted on having a meal with my parents, who were simple country people intimidated by the very notion of Ron Barassi but came away charmed by an easygoing man who took an interest in their lives and who laughed easily and often. I remember looking at Dad and thinking how annoyed he, a Hawks supporter, was by the cult of Barassi and seeing that he too was now a paid-up member of the tribe.

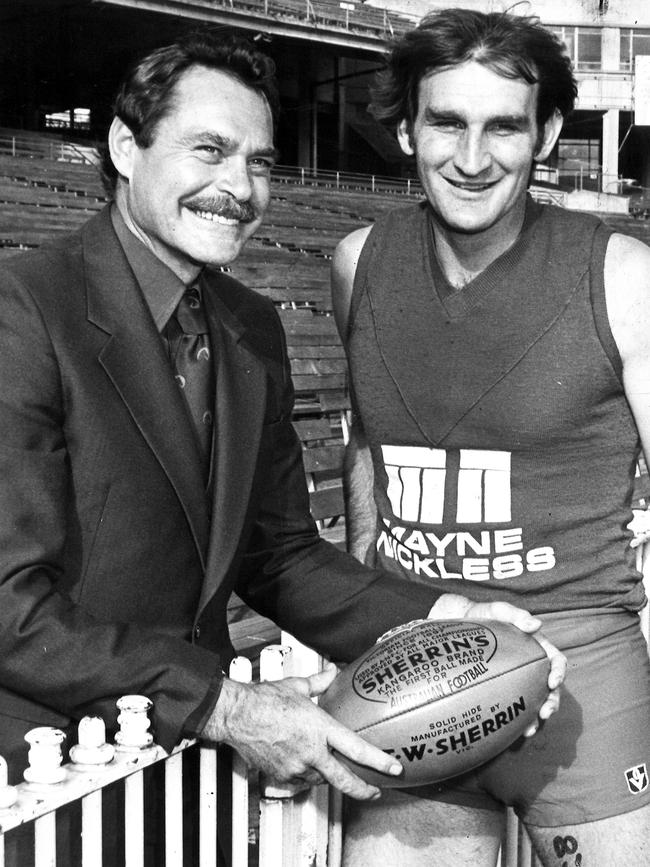

Barassi had an impish sense of humour, an easy smile that lifted from beneath that bristling moustache and a way of putting everyone at ease.

He was as gentle off the field as he was rough on it. Bred with 1950s manners, he had an old-school politeness.

He had a bone-crushing handshake for men and a gentlemanly way with women.

As he got older he became more emotional and he would cry often when we’d speak of the father he’d barely known.

Walking the street with the barrel-chested Ron was an experience – everybody knew him and he had a smile and a wisecrack for anyone who stopped him.

Driving in a car with Ron was terrifying. He drove as he played, throwing the vehicle into packs, almost getting us killed between two trams out at Coburg one day. It was no surprise that he was involved in a number of car accidents over the years. He drove fast and distracted, always keen to get to the next place.

In life he was similarly restless and inquiring. Always looking for a new project, a new way to do something.

The Barassis migrated from Italy and set up home on Shicer Gully Road out the back of Guildford before Ron Barassi senior moved to the city with his young wife, Elza, to play football with the powerful Melbourne football club in the late 1930s.

Ron’s dad played in the 1940 premiership side alongside the great Norm Smith, but was not in the team photograph as he’d joined the army and was on his way to Tobruk the next day. He was killed halfway through the following season, leaving behind a young wife and son who were taken in by the club.

Ron junior eventually moved into a self-contained bedroom at the back of Smith’s suburban Melbourne home when he was a teenager.

Smith was now Melbourne’s senior coach and one of the great football partnerships was set in motion. At first he did not know what to do with the barrelling, bustling boy who would run through brick walls but who was not big enough for a key position or small enough to rove.

Eventually, Smith created the role of “ruck rover” and Barassi, who would wear the 31 jumper his father had worn, would become the game’s first modern midfielder. There’s magnificent mid-century photos of Norm greeting Barassi at the front door in his dressing gown to break the news he would play his first game and another of Norm’s wife, Marj, ironing the 31 jumper in anticipation of the event.

Together Norm and Ron won six premierships. Ron was one of the league’s highest-profile players and one of the most fiercely devoted footballers of his time. Twice he was the Demons’ leading goal scorer, he captained the team to the 1960 and 1964 premierships, and three times he made the All Australian side.

Few who ever played the game could match his levels of desperate determination or skill but Norm Smith was a hard man, a strict disciplinarian with a scolding tongue, and he reserved the worst of his tirades for the boy who lived out the back of his house, but the results on the field were spectacular.

Barassi was Melbourne and Melbourne was Barassi, but the footballer had greater ambitions. He wanted to coach, but Smith was in his way, and eventually he decided that he had to go.

Footballers come and go regularly in the modern game, but when it was announced that Ron Barassi was leaving the Demons to play and coach at Carlton it shook the state. Newspapers announced that loyalty was dead, fans wrote to newspapers for advice on changing the names of pets called Ron or Barassi; others set about tearfully unpicking the number 31 from the backs of children’s Melbourne jumpers, while one fan even burnt one.

Richmond legend Jack Dyer said at the time that it wasn’t a guernsey Barassi wore to play but that his skin was Demon colours. “He personified everything that meant loyalty and devotion,” he added.

It could be argued it was the move that made it OK to be more than a one-club player, an act that redefined loyalty.

“Where is your heart, Ron?” television commentator Mike Williamson asked him on air at the time.

“Right here, Mike,” he said, smiling broadly and pointing to the place where it normally resides.

“I think your heart is where you are at the time,” he continued.

Carlton was over the moon, but the grocers on Lygon St were disappointed to discover that this Barassi did not speak Italian. It was at the Blues that the notion of the super coach was born.

When Barassi was one of the first 12 legends admitted into the AFL Hall of Fame in 1996, Blues historian Lionel Frost said: “Only Barassi comes close to earning selection on the strength of his coaching record alone. Inspirational, courageous, determined, brilliant as a player, Ron Barassi was all this and more. He played in six Melbourne premiership teams, twice as captain. In 1959 he gave what is widely regarded as the greatest performance in a grand final. Yet for all that, Barassi will probably be best remembered for the four premierships he won as a coach.” Frost said Barassi was football’s equivalent of the “big bang”.

It is a fair call. He was revolutionary as a player, a coach and a media personality.

Former teammate and later a Victorian politician, Brian Dixon, said of the move from Melbourne to Carlton: “Who is better qualified to devote himself even more exclusively to football than Ron Barassi?”

And yet Barassi bristled at the perception that he only knew football.

“I’ve always fought against the assumption that football was my whole life,” he told me in 2010. “It’s much more than that. It’s been … a lot of football. I understand all that stuff. There were a lot of other things I would have loved to have done and I’m interested in a lot of other things … in football I found the right outlet for my determination. Determination is necessary for all sports at the top level, but in footy courage and determination to catch the bastard with the ball and make sure he doesn’t get you, the hunt when he’s marking … I was definitely that sort of footballer and I loved it. Right from the start.”

Barassi had three children with his first wife but his life almost tracked the times. He left the suburbs and the family when he began coaching at Carlton, grew his hair, changed his style and took up with his lifelong partner, Cherryl, an artist, whom he married in 1981.

The couple have lived most of the past four decades in a two-storey apartment on St Kilda beach, moving to the suburb long before it became trendy. She painted, and he set about various business interests that over the years included the furniture trade and pubs.

He was a keen collector of football memorabilia. Only recently was his collection moved from the home and various storage units. It was bought by Paul Little, who is attempting to find a place for it after Melbourne and the MCC said there was no room.

Barassi walked the Kokoda Track the year he turned 70 and while his body was ravaged by the beatings he’d put it through as a player, he kept active, riding a bike, keeping up with friends and travelling.

He was, however, never far from the news or the game. On Christmas Eve 2009, Barassi came to the aid of a woman being attacked on Fitzroy St in St Kilda, chasing her assailant down the street while bystanders looked on. The woman was rescued but Barassi was thrown into a gutter and kicked in the incident.

We were working on the book around that time and it was becoming obvious that Ron was not as sharp as he’d been and his memory – always questionable – began to fade further.

“There’s not much I could do about it,” he told me.

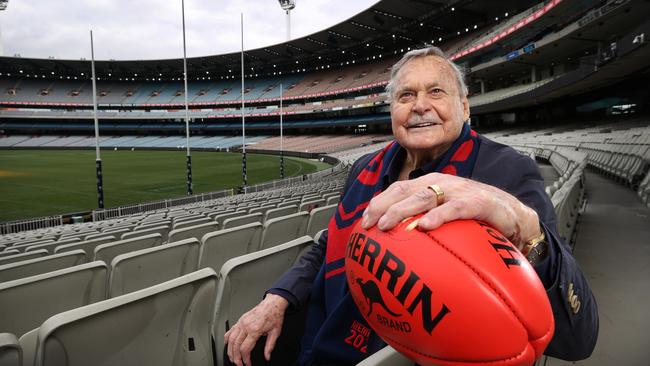

He was a constant at Melbourne games and in 2021, when the side won its first premiership since he’d left, all eyes turned to the grand old man of the game.

On the eve of Melbourne’s clash with Carlton this week footage emerged of Ron Barassi’s last-ever game of football.

Nigel Buesst, a stringer from the ABC, had recorded the game on his Olex 16 camera on Saturday, May 17, 1969 and edited it together as a package. It’s a haunting document of another era, in colour but not the colours of our time.

The coach had earlier retired from the game but pulled on the jumper one last time so he could bring up his 50th match for the club, which would ensure his sons could choose between Melbourne or Carlton under the father-son rule should they play.

Barassi broke down in the second half, had a shower and returned to coach the side at three-quarter time back in his civilian clothes.

There’s a Ron Barassi-sized hole in football now that’s hard to contemplate. For most of us he has been there at every part of the journey. I concluded over a decade ago that “People always need a hero. Ron Barassi was and is just that … He embraced his sport and its heroic spirit with the integrity heroism demands. He embodied the game’s creation myth, its shift from quasi amateurism to passionate professionalism. He was the player who had wrung more from the towel, the coach who lifted men to heights they never knew they were capable of”.

In 1941 the Sporting Globe paid this tribute to his father and the words are equally apt for the son.

“Ron Barassi came from the country an unheralded country lad, and made a name in our national game for his sportsmanship as well as his ability. He departs a man honoured by his peers and those who cheer.”

Ronald Dale Barassi is dead and the magnitude of what has passed is impossible to quantify.