Tuck’s legacy: it’s not mental health, it’s brain damage

Shane Tuck was tormented by the voices in his head. Now his family reveal the heartbreak of the deadly disease that took his life – and ask why the AFL is not doing more to protect footballers.

At first, the voices in Shane Tuck’s head spoke to him like angels. But as the months wound on, they became sinister beings and soon they began to tell him to take his life.

“You don’t need to be here, why don’t you finish yourself off, Shane,” the voices told him. “You don’t need to be here anymore.”

Shane’s mother, Fay, recalls the extraordinary pain and anguish the 38-year-old former Richmond player was experiencing. The legendary football family sent Shane to countless doctors and therapists, even trying electroshock therapy. “The wonderful practitioners at Monash Health down at Pakenham, they hit him with everything,” Fay says. “We had the top doctors … we spent a lot of time and money trying to diagnose what he had, but he had them baffled.”

Nothing seemed to work. The former AFL player was spiralling. By April 2020 he had tried to take his life twice within 12 months.

“I don’t know how much longer I can go on with this,” Shane would often say to his mother around this time. “Mum, I don’t want to go, but I need to go, because I can’t find any peace.”

Fay makes it clear her son did not have “mental health battles” because – unbeknown to him and his loved ones at the time – his brain was “ravaged” with chronic traumatic encephalopathy, a disease experts say was caused by his 173-game AFL career. “It’s a real sickness of the brain, it’s totally different to mental illness,” Fay says.

Shane took his life in July 2020. A 2023 coronial inquiry into his death made a raft of safety recommendations to the AFL – including two major initiatives: restricting contact in training, and introducing independent doctors – in an effort to mitigate brain injuries including CTE, but 18 months on the league is yet to implement either of these key measures.

“I thought Shane’s legacy would be worthy of something, because he had gone through so much and we had fought so hard,” says his sister, Renee Tuck. “Instead these key recommendations made by the coroner, John Cain Jr – restricting contact in training and introducing independent doctors – have not yet happened.”

The AFL is facing a class action by more than 100 former players who claim to have an acquired brain injury as a result of the AFL’s failure in past years to implement basic concussion protocols, as well as calls for it to be prosecuted for workplace manslaughter over the deaths of at least four players who suffered traumatic brain injuries.

The AFL has said there is “no higher priority” than the health and safety of players. It also has previously said it is continuing to research and measure contact in training as it “considers” implementing the coroner’s recommendation.

While it has already agreed to the coroner’s instruction and introduced concussion spotters – “empowered to mandate that a player be removed from the game” – the game has still been marred by several controversial decisions not to remove players quickly.

Concussed Geelong player Jeremy Cameron waved away the club doctor last season and played on. The game was not stopped after Collingwood forward Lachie Schultz suffered a hit last month and collapsed in the arms of trainers.

Shane’s father, Michael Tuck – one of the game’s greatest players – says he would like to see even more safety measures in light of his son’s death. He would also like a longer rest time for players suffering head trauma, with some sports-focused neurologists recommending a four-week break.

“I just think it’s negligence by the AFL, technically, because they know what’s going on, but they’re not doing a lot about it,” Michael says. “They say they are, but a bloke might get a week off (when) some blokes need probably four or five games, actually, to get right over it (head injury).

“Basically, if you left everything with the AFL, it would be like the Labor Party; do what they say, you just have to cop it. I respect the genuine supporter and the people love their football so it’s a very hard situation, but you’ve got to protect the person.”

‘He’d had enough’

Five years ago, Shane’s wife Katherine, Renee, Michael, Fay and younger brother Travis were fighting daily to try to save the former AFL player’s life.

By early 2020, with the support of his family, Shane was living back at his childhood home, trying his heart out to stabilise his mind. But the voices by then were dominating his life.

Michael remembers Shane screaming so loud at the voices one day to “piss off” that it caused a commotion in their neighbourhood. “Even the blokes working two doors down stopped work, they thought there was someone getting murdered up here, so, he just couldn’t control himself basically,” Michael says.

The family were “living on a prayer and on edge”, says Renee.

Fay recalls she and Michael would be invited out but would have to politely decline, because they were both scared to leave their son alone. “My soul told me not to leave him,” Fay says. “He was in so much pain and agony at times … I wasn’t going to leave him. The only thing that kept him going was the love of the family – no one knew what we were going through … we’re not that sort of family to complain.”

And then, on a winter’s evening – July 19, 2020 – Shane came upstairs from his room and gave his parents “a big hug”. “He put his arms around us and said ‘I really love you guys’,” Fay remembers.

At that moment Fay was slightly alarmed. “You’re not going to do anything, are you?” Fay asked.

“No,” Shane replied.

Fay, Michael and Shane sat down for a roast lamb. As they chatted over dinner, she looked at the expression on her son’s face across the table. “I knew the whole time what he had on his mind,” Fay says. “He’d had enough.”

At peace, finally

That night, Fay could barely sleep. Michael checked in on Shane at midnight and 3am – his son was safe, asleep. At 4am Fay also checked in and found him sleeping soundly. Fay’s heart was relieved.

“He’ll be right, because it’s close to morning now,” she thought, and allowed herself to rest.

Fay and Michael rose after 8am. They couldn’t find Shane. Maybe he’d ducked out for something to eat. But his car was still out the front. Michael began to panic. They searched frantically around the house. It was Michael who found him. As they waited for the ambulance, Michael and Fay placed a pillow under their son’s head and a blanket over his lifeless body. Fay remembers her son’s expression at this moment.

“He looked at peace for the first time – that strain on his face had gone,” she says. “I was a little bit at peace myself, as awful as it sounds, because it was the first time I saw his face with no strain on it and no wrinkles, and he looked very peaceful. I said to the paramedics that picked him up for the coroners: he won’t need an autopsy (on his body), there’s no suspicious circumstance. I said they’d find it up here, in the brain, and I said to them that I wanted to donate the brain because I needed the answers.”

Shane’s brain was taken to the Australian Sports Brain Bank in Sydney. When chief neuropathologist Associate Professor Michael Buckland placed Shane’s brain under the microscope he saw “shocking damage” – the worst case of CTE he had encountered.

Silent killer

In her first extensive interview on their loss, Fay explains she felt moved to tell more about Shane’s story because, as calls in the AFL grow louder for mental health rounds, the real issue of CTE is being lost in the noise.

“It wasn’t mental illness, it was brain damage that caused Shane to take his own life,” Fay says. “I am still terribly broken-hearted but I understand now, from Dr Buckland’s explanation, why he had to do it; Shane’s brain was an absolute mess. He did well to get as far as he did. As a mother, once you understand that, it makes it just a tiny tad softer. Now I understand how he felt. CTE is real. A lot of people don’t want to know about it, they turn their back on it, because, I mean, all this diving on the football, I still noticed last week’s round, some guys throw other guys heads to the ground … they’re not supposed to.”

CTE is a progressive, degenerative brain disease linked to repetitive head trauma. Its symptoms may not appear until years after the onset of head impacts, and can include behavioural problems, mood swings, memory problems – at worst, it makes sufferers suicidal. The disease has been found in the brain post-mortems of St Kilda champion Danny Frawley and rugby league premiership-winning coach and former player Paul Green. Both had CTE; both died by suicide.

Renee Tuck would like the conversation to shift to the heavy impact the game can take on players’ brains. “There’s been a lot of calls for mental health rounds, which triggers us – not to say that mental health is not a worthy cause to invest in – but CTE took my little brother,” she says. “It’s a silent killer but then it’s like a volcano erupting … we are going to see more and more deaths from this disease if nothing is done. We didn’t know what CTE was. Now everyone needs to know, but no one in the AFL is educating their players and community on it. What isn’t shared often enough publicly is the absolute pain and trauma, not only of young men taking their own lives, but the absolute fight the families are in up to that point.”

And fight the Tuck family did.

True grit

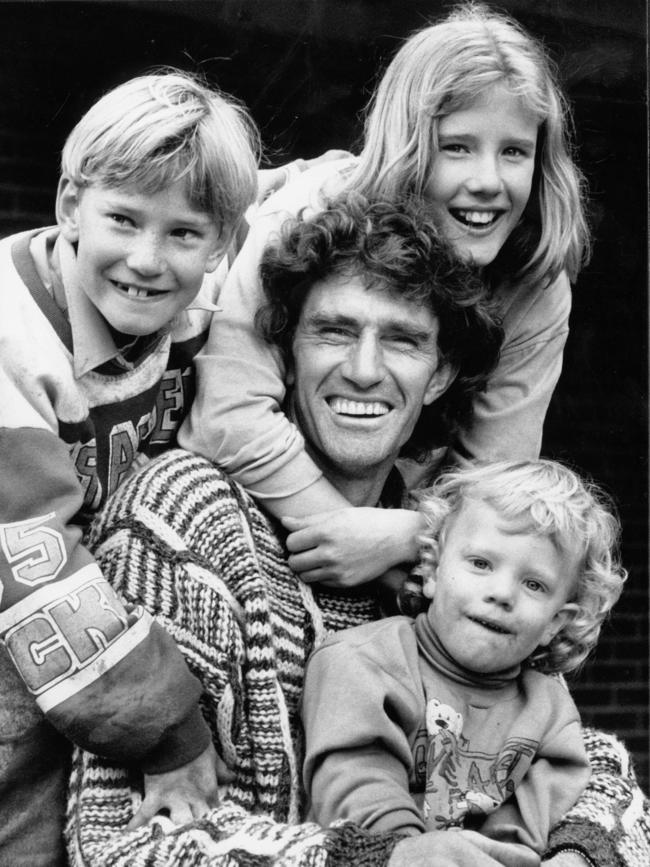

As a young girl, Renee recalls running around the wooden stands of Waverley Park and Glenferrie Oval with her two brothers, while Michael played footy and collected seven premierships for Hawthorn during his 19-year career.

Renee has fond memories of herself, Shane and Travis making their way down to the dressing rooms, five minutes before the final siren, to be sure not to miss out on a can of Coke and some party pies. “Our childhood was amazing and we got to do it all together, the three of us,” she says.

By the time Shane was a teen he was dreaming big, with his family backing him the whole way.

His AFL career began slowly. Hawthorn picked him in the 2000 rookie draft but he was delisted after two seasons without playing a senior game. Still, he fought on, playing in the South Australian league. At the age of 22, Richmond selected him, 73rd overall, in the 2003 draft.

In 2004 he played his first AFL game. “He came back from nowhere basically and made it, and he worked very hard to get there,” Michael says.

Shane played every game in 2005. He was a gritty, brave player who finished third in Richmond’s best-and-fairest award that season. He was regarded as “a warrior”. “He was a diver on the footy field, he was always diving over the ball,” Fay says. “He suffered knocks, and belts and bodies falling on him.”

Michael says Shane was “always tougher than me”. “And I think his football proved it,” he says. “He was always in the bottom of the pack and I think he got a lot more knocks to the head that a lot of other blokes wouldn’t get.”

Shane played 173 games for Richmond over the course of a decade, retiring in 2013. But as his footy career wound up, and ultimately finished, his behaviour started to change. But in a quest to keep pushing his physical limits, to fill a gap footy left, he tried boxing.

The voices begin

In 2015, two years after retiring, he took part in his first professional bout, on the undercard of an Anthony Mundine fight. Shane was knocked out in the fourth round. He suffered a bruised brain and was hospitalised.

By the end of 2015, for the first time, he was expressing suicidal thoughts and was hospitalised, again. In January 2016 he was hospitalised after experiencing “pain” in his head.

Buckland suspects from studying Shane’s brain that the damage would have begun in his late teenage years or early 20s.

“Based on the appearances I would think that the disease had been there for at least 10 years and probably closer to 20 years,” Buckland says. “We know there are cases reported in 17 (and) 18-year-olds in the US. We also have a case in the Brain Bank of the former Sea Eagles junior and schoolboy Keith Titmus, who was just 20.

“This disease can start when you are a junior athlete, we don’t know if all start as young athletes – but we have evidence that some of them start.”

He adds: “Just like Alzheimer’s disease there is a pre-symptomatic phase of the disease – so that means that there may not have been signs of the disease when it was developing in his brain in those early stages.”

By 2017 the voices had started. Michael, Fay and Renee pinpoint the moment they knew something was “very, very wrong” with Shane was in 2019. It was May when Katherine called them from Adelaide, where they lived with their two little children, to say Shane had made an attempt to end his life and was in hospital.

As a family it was decided Shane should spend some time living with Fay and Michael, back at the family home in Berwick in outer Melbourne.

The voices had well and truly taken to running his life. It was a horribly confusing and distressing time for the family. “What the hell is happening with my little bro?” Renee often thought.

‘That’ phone call

Shane was on a number of medications to try to recalibrate his mind. Renee would check in with him daily to make sure he took them.

“Yes, Renee, but the meds don’t work,” her brother would say. “The voices aren’t going away, they never will.”

The family pushed on, supporting him with nothing but love and hope. Meanwhile, a team of health workers led by Shane’s psychologist, Louise Steel, was unrelenting in its care for him. “Dr Steel fought alongside all of us for him,” Renee recalls.

As his life unravelled, Shane was stuck in the midst of lockdown with its Covid border closures, and was unable to see Katherine and his children, causing him immense distress. In April 2020, Travis called to say Shane had attempted to take his life for the second time. By this stage, Renee says, she had come to fear phone calls from her family. “I was just waiting for ‘that’ phone call,” she says. “Your nervous system is running on empty.”

That call finally came on the morning of July 20.

At his funeral, Katherine paid testament to Shane as a dad.

“We know that your two biggest achievements were Will and Ava, and I will keep your memory living on in their lives,” she said.

Michael says his son didn’t take the easy way out. “For Shane, it was not an easy way out, it was the only way out, so that’s where there was a sad part,” Michael says. “He loved his kids and he loved his wife, and then it (CTE) just sort of ruined his total life.”

As Shane’s body was lowered into the ground, Fay says a part of her went with her son.

“All my children are my soulmates,” she says. “And he and I are soulmates, like everything I told him, went down with him … He did die knowing that he was loved.”

Silence of the AFL

Since Shane’s death, Renee has heard the repeated refrain that footballers know what they are getting into when it comes to playing the game and the potential for brain damage.

She says this is untrue.

“I have heard some bystanders and supporters say ‘they play footy, they know what they’re getting into’ or ‘they get paid enough’,” she says. “But this is not true. No one who was made aware, as Shane was not, would ever wish this upon themselves.”

Despite Shane playing his heart out for his club, Renee says the inaction of the AFL has been telling. “After Shane died he got a minute’s silence at a Richmond game – we never heard or saw anyone from the AFL again,” Renee says.

Renee notes Shane was a player who copped knees, elbows and feet to the head. He was in scrums putting his body on the line, round after round. “Shane wanted so much to do his best and he put himself through the ringer for it without complaints,” she says.

The silence of the AFL and its powerbrokers may sting, but the Tuck family remain strong on the issue, saying the game needs to be made safer. “I don’t want to ruin the game that was my father’s livelihood,” Renee says. “It’s not about that … but you can’t not talk about CTE taking young sports people’s lives. I’m confused that that is not spoken of more … education, knowledge, that’s all people need to prevent this.”

Renee thinks Shane would approve of her “dramatic attitude” being put to good use in her push for better player safety and more awareness around football’s link to CTE.

“I know that he knows how much I love his children and he knows I will always do what is right,” Renee says. “Shane would be saying; ‘well, all that pain was worth something – me having to leave my kids was worth something’ … because he definitely wasn’t living at the end, and he had to put himself to sleep. You wouldn’t even keep an animal alive that was suffering as much as he was.”

If you or someone you know is at risk of suicide, call Lifeline (13 11 14) or the Suicide Call Back Service (1300 659 467), Beyond Blue (1300 224 636), or see a doctor.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout