‘Corporate bastardry’: Betrayed players turn on AFL

The sport’s governing body has been accused of deliberately ignoring evidence of catastrophic brain injuries in a bid to avoid liability for up to $2.5 billion in legal claims.

The AFL faces calls it should be prosecuted for workplace manslaughter over the deaths of at least four players who suffered traumatic brain injuries, with the sport’s governing body accused of deliberately ignoring crucial evidence in a bid to avoid liability for up to $2.5bn in legal claims.

The Australian can reveal that brain scans of nearly 20 former AFL players show catastrophic injuries – worse in some cases than car-crash and war-related blast victims – causing neurological dysfunction ranging from depression, anger and wild mood swings to domestic violence and suicide.

The AFL Players Association, which is primarily funded by the AFL, is expected to announce an expanded injury and hardship fund next week – some believe in a belated attempt to counter a legal class action by more than 100 players.

But it comes too late to stem the mounting anger of victims devastated by permanent brain damage and left for decades without help from the nation’s richest sporting league.

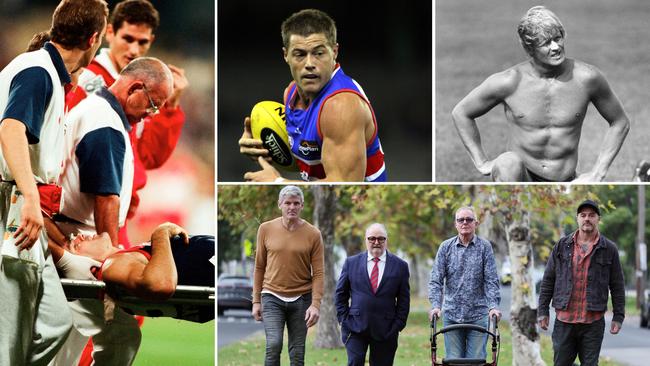

Veteran player agent Peter Jess, who represents dozens of past and present footballers including Shaun Smith, Alan Stoneham and Matthew Robbins, told The Australian that within the AFL was “an awful group of people who deal in corporate bastardry at the highest level”.

“The only comparison we have is the James Hardie asbestos case, which is deny, defend, defer – they hope many of these guys, they’re just waiting for them to fall off the perch and die before they deal with these claims,” Mr Jess said.

Susan Rudolph, the long-time partner, now carer, of brain damaged Western Bulldogs footballer Nigel Kellett, said she had been “ghosted” by the AFL after a meeting last year. She recalled the meeting at AFL House involving herself, Kellett and officials as “really emotional”.

In February 2021, Kellett was formally diagnosed with frontotemporal dementia (FTD), “probable” chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), depression and a form of Parkinsonism, which neurological experts said he had likely acquired from repeated collisions and subclinical concussions suffered during a 10-year career.

The 55-year-old, who stopped working because of his brain injury in 2021, has planned and attempted at least six suicides in recent years, being hospitalised and institutionalised in secure facilities along the way.

“In the June 2024 meeting at AFL House we were told, ‘unfortunately, it’s not like we have millions of dollars’ – but they do with over $1bn in revenue just last year,” Ms Rudolph said.

“It’s where they choose to spend those dollars and they are choosing not to spend it on these past players who are suffering. They’ve only been talking about it.”

Despite several follow-up attempts, Ms Rudolph has heard nothing from the AFL. “They were going to get back to us,” she said. “We basically got ghosted.”

Mr Jess has asked WorkSafe Victoria to investigate and prosecute the AFL for failure to safeguard players from preventable brain trauma. “The irrefutable evidence is that science and medicine indicates that chronic traumatic encephalopathy has been confirmed in the AFL neuropathologically post mortem for ex-AFL players including Danny “Spud” Frawley, Shane Tuck, Craig Stewart … who died with CTE,” Mr Jess told Victorian WorkSafe Minister Ben Carroll.

Both Tuck, 38, and Frawley, 56, died by suicide.

Chronic traumatic encephalopathy is a degenerative brain disease, linked to repetitive head impacts, not just concussions.

It can only be conclusively diagnosed by a post-mortem examination of the brain, but experts say scans such as magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and magnetoencephalography (MEG) can be used to assess the extent of damage in living victims. Mr Jess alleges in a complaint to WorkSafe that the AFL failed to comply with its occupational health and safety obligations, including by its refusal to use MEG scans, a diagnostic tool, which its owner, Innovision, says has an accuracy level of 86 per cent compared with the 10 per cent accuracy of fMRI scans currently employed by the league.

“The AFL’s negligence in not requiring MEG scans has led to preventable deaths and the AFL should be prosecuted for industrial manslaughter,” Mr Jess said.

In a statement to The Australian, the AFL rejected that submission. “WorkSafe Victoria has on two separate occasions over the past five years thoroughly investigated the management of concussion and head trauma by the AFL and Victorian based AFL clubs and not pursued any action under the Occupational Health & Safety Act,” an AFL spokesperson said.

WorkSafe Victoria said it was “aware of ongoing concerns regarding the management of sports-related concussion risks in the Australian Football League.”

“Inspectors continue to monitor the issue and any available evidence to ensure occupational health and safety obligations are being met,” a spokesperson said.

WorkSafe did not address specific questions about whether it was considering a prosecution for workplace manslaughter, but under the OH&S Act an extremely high degree of negligence would be required to support such a move.

Leading neuroscientist and sports concussion researcher Alan Pearce said a “tool kit” of scans, including neurological tests as well as taking in a player’s clinical history, should be used when trying to meet the criteria of traumatic encephalopathy syndrome (TES), a clinical disorder associated with CTE.

“So these scans are very good but they’re only part of the tool kit - there’s no one gold standard over the other,” Dr Pearce said.

“MRIs, PETs, MEGs, and the testing I do, TMS (transcranial magnetic stimulation), in isolation they can’t give the full story, they all have to be part of a multimodality tool kit for us to fully have confidence (in the diagnosis).”

Mr Jess has paid for several $8000-a-time MEG scans out of his own pocket after the AFL reneged on an agreement to reimburse him. But the long-time player advocate believes the high cost of the tests is not the only reason the AFL won’t play ball.

In a letter to the AFL earlier this month, Mr Jess accused the league of refusing to fund MEG tests in a deliberate bid to conceal and understate the damage caused by repetitive brain trauma.

“The lack of continuous testing and scanning of participants’ brains is the root cause of this industrial disease”, Mr Jess said in the May 7 letter.

“I have been and continue to be confronted by the AFL’s manipulating science, promoting ‘friendly research’ with the elimination of any reference to the actual neurological harm from the AFL’s testing programs and return to play protocols,” he wrote.

‘Negligent’

Research conducted by the Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport in 2013 revealed that the daily living of at least 73 per cent of past AFL players was impacted by concussion.

When former Western Bulldogs player Robbins, 48, underwent a MEG scan, the examiner reported: “Very sadly, these reveal the most severe signs of brain injuries we have seen in scanning over 100 individuals (including military blast injury victims).”

Robbins’ brain’s cortical points were 91 per cent damaged, the tests revealed – clear evidence of massive brain damage. But when Mr Jess forwarded the scans to the AFL, he said he did not receive a response.

“This should have prompted the AFL to review previous scans and to discontinue the fMRI scans in future projects,” Mr Jess said. “This is negligent beyond belief, in spite of the warnings of the ineffectiveness of the fMRI scans.”

The AFL never reached out to Robbins to check on his health or welfare. Robbins reveals that while his previous fMRI scan showed no concern, the MEG scan result was frightening.

“It’s pretty scary – of 68 points of functionality, I have damage to over 50,” Robbins says.

“It is scary but it’s about setting myself up for my family (for my future), I enjoyed and love the game but I am feeling the effects of it.”

Robbins, who played 146 games and suspects he had more than eight concussions, said he had struggled with depression and now short-term memory loss.

“My short-term memory loss is becoming an issue,” he said. “Working as a tradesman, I now have to write down my measurements, I have to adapt … that’s what I’ve been dealt with unfortunately.”

Mr Jess claimed many players were notified by the AFL’s medical team that the results of the standardised fMRI scans showed “no clear post-traumatic features”.

“The players were informed that they were not at risk of the broad spectrum of neurological disease such as the early onset of dementia, CNI, CTE or any other neurological degenerative diseases,” Mr Jess said.

Tests ‘gone missing’

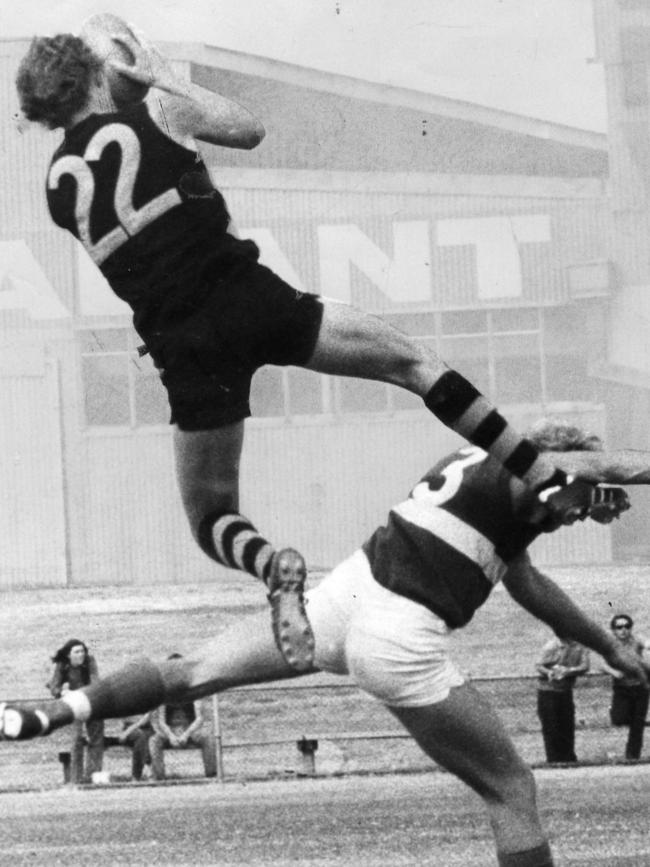

One player who was told he had nothing to worry about was Stoneham, a former Footscray and Essendon great.

When Stoneham, now 69, requested his previous fMRI brain scan from the AFL’s Past Player Concussion Program he was told it had gone missing.

“They were using it in the study, I was told it was all fine,” Stoneham said.

“It took a couple of years to get something done (to get an independent MEG brain scan).”

When he did a MEG scan it revealed brain damage so severe that he had to have a plug inserted into his skull to drain fluid from his brain, a condition known as hydrocephalus.

This was “created by multiple brain traumas undetected … by the AFL concussion programs and by his blub doctors during his AFL career”, Mr Jess claimed.

Stoneham believes the league has relinquished any responsibility for those like him who are suffering. “The AFL seem to want to wipe their hands of all responsibility,” he said. “I felt I was treated poorly.”

Stoneham, who can’t work, is being cared for by his wife most of the time.

“She’s basically my carer,” he said. “My wife (Julie) is traumatised more than me, I suppose.”

The pattern was repeated in the cases of players such as John Barnes, Kade Kolodjashnij, Daniel Venables, Chad Rintoul and others, Mr Jess said.

Brain lesions and other structural damage remained undetected and undiagnosed.

Many former players who believe they have brain injuries have been refused help by the AFL and the AFL Players Association because they are unable to prove they suffer from CTE.

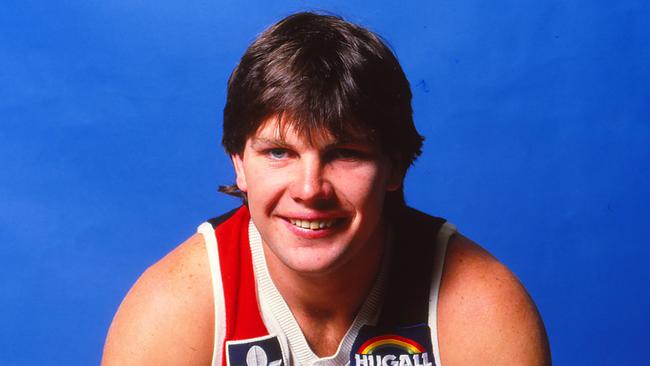

When former Footscray and Richmond player Alan “Dizzy” Lynch developed Parkinson’s disease, his family were in no doubt it was from a professional lifetime of head-knocks.

But even as his behaviour became more and more violent, the AFL refused to help.

When Lynch died last year, aged 70, his family donated his brain to the Australian Sports Brain Bank but the findings are yet to be released.

“Where is the compassion?” Mr Jess asked in his letter to the AFL. “Where is the humanity?”

Worse for women

The impact of CTE on women playing in the AFLW would be “more catastrophic than their male counterparts”, Mr Jess warn.

Former Adelaide Crows player Heather Anderson was diagnosed with CTE in a post-mortem after taking her own life in 2002 at the age of 28, the first professional female athlete to be diagnosed with the degenerative brain disease.

“The AFL has failed to change the AFLW from men’s rules to protect the cohort,” Mr Jess said.

“I warned the AFL that to let the AFLW develop with men’s rules will lead to deaths on the pitch, either directly or indirectly. To date we know of four such deaths. Nothing has changed since I warned the AFL.”

Maggie Varcoe, 27, the sister of AFL footballer Travis, died after a head clash with one of her teammates during the Adelaide Football League grand final in 2018.

Former Giants player Jacinda Barclay, who took her life at 29, was found to have neurological damage, although not CTE, with the Australian Sports Brain Bank describing her brain as a “ticking time bomb”.

In 2022 Elisabeth Memos, 23, had a stroke that was linked to a community match she played four weeks earlier, when she was accidentally kicked in the head and concussed.

Mr Jess has for years been urging action against the AFL for breach of the OH&S Act, and thought he had achieved a breakthrough in 2019 when WorkSafe agreed that the issue would be investigated by independent experts in the concussion field. But WorkSafe refused to identify its chosen experts.

It was only when Mr Jess lodged a case with VCAT to force WorkSafe to name them did he learn that the two “independent experts” were doctors Andrew Gardner and Andrew McIntosh, who had both been part of the AFL’s concussion research team.

The pair were “hopelessly conflicted”, Mr Jess claimed, and “confirmed the AFL provided a safe workplace in spite of the overwhelming science and medicine to the contrary”.

A 2021 paper co-authored by Dr Gardner determined that there was no link between concussion and risk of depression and a co-authored 2024 paper with Dr McIntosh questioned the evidence between repetitive collisions and CTE.

Dr Gardner, who is also the NRL’s lead researcher, has publicly said CTE is a “hypothesis” that needs to be “tested”.

Dr Gardner and Dr McIntosh’s 2024 paper was also co-authored by Rudy Castellani, a professor of pathology at Northwestern University in the US, who has said CTE is an “invented disease … conjured out of thin air” by Boston University.

“These articles confirm my scepticism of the behaviour of the AFL and WorkSafe as a health and safety regulator in AFL,” Mr Jess told the AFL.

The conclusion by the “independent experts” was that the AFL provided a safe workplace in a period when, on average, 100 brain traumas per season were being recorded and five players were retiring from the impact of brain traumas and being classified as totally and permanently disabled, Mr Jess claimed.

“In my view, in concert with the AFL, WorkSafe corrupted the process to keep the industry safe,” he said. “The AFL was more concerned about generating more revenue whilst being totally unaccountable for its actions.”

Legs before brains

Mr Jess has for years advocated a program developed by the University of Cincinnati that reduced concussion incidents by 80 per cent over a 10-year period, but he claims the AFL’s failure to adopt it has resulted in year-on-year increases in concussions and brain trauma.

Mr Jess points to evidence that concussion and brain trauma are not the same: the symptoms of concussion may resolve but the brain injury created by the event is permanent.

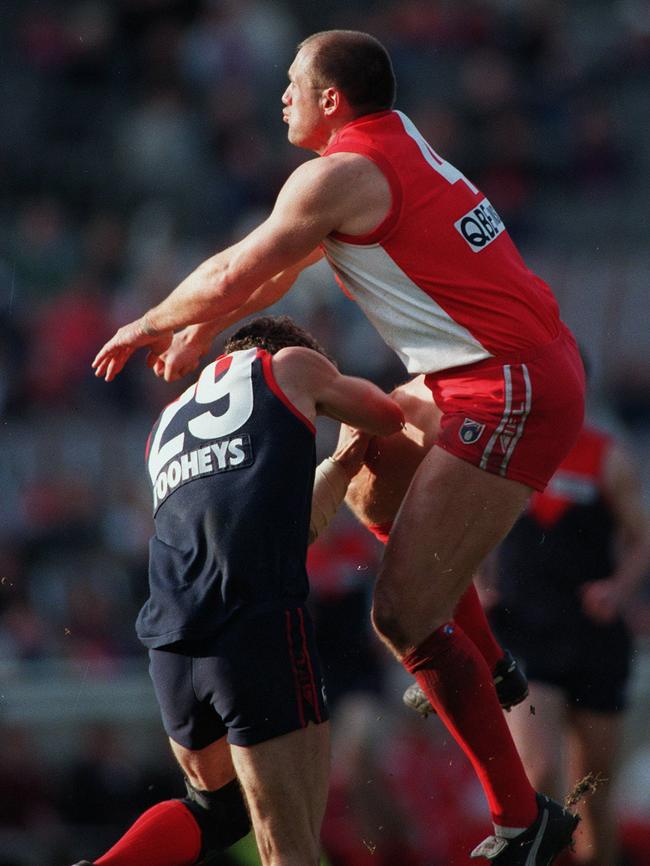

Smith, a forward who played 109 games for North Melbourne and Melbourne and is known for taking the “mark of the century” against the Brisbane Bears at the Gabba in 1995, has a brain injury from his career.

“Thank god for Peter Jess: whether you love him or hate him, he is doing something,” Smith said. “It’s a horrific (scene) with so many past players suffering, but even in the modern game you’ve had Liam Picken, Jack Frost, Paddy McCartin, leave the game (and) Kade Kolodjashnij.

“If the AFL are saying they are doing the right thing they are full of shit.”

He added: “These are men living with brain injuries for the rest of their lives.”

Smith points to Collingwood player Lachie Schultz, who was recently knocked out and became the centre of intense controversy when the game failed to be stopped. He collided with Fremantle defender Jordan Clark in the middle of the ground, and then collapsed while attempting to jog off the ground in the company of a pair of trainers. Eventually the AFL conceded its on-field process “failed” the player.

Smith said the scrutiny should also be on the fact that Schultz would only have to miss one game under the AFL’s 12-day concussion stand down policy.

“His body went rigid and yet he will miss one week and play … the science says 28 days-plus – it’s just nuts,” Smith said.

“The sad thing is that if a footballer breaks their leg, they miss eight weeks – we seem to not give a shit about the brain.”

In 2022 the AFL said it would ask Gordon Legal to continue consulting on the design of a no-fault assistance scheme for players who had suffered debilitating head injuries during VFL and AFL playing careers. It is yet to come to fruition.

The AFL told The Australian it had “no higher priority” than the health and safety of AFL, AFLW and community players.

“The AFL continues to enhance the management of concussion in Australian football where possible and appropriate to do so,” a spokesperson said.

“The AFL has made dozens of changes to its rules over the past several years to make the game safer by reducing the amount of avoidable forceful high contact.

“This season we are using our independent doctors that are in the AFL review centre, we have allowed them to have more direct authority in relation to head-injury assessments and being able to direct that a player be taken from the field for assessment.”

The spokesperson said the AFL had embarked on a 10-year, $25m longitudinal research program that would “measure the impact of playing Australian Football on the brain health of its elite players to inform policies at all levels of the game”.

But for past players such as Kellett, who need help now, the promises ring hollow.

$1m promise evaporates

In a November 2022 letter to the former Footscray footballer, seen by The Australian, Peter Gordon, acting on behalf of the AFL, said the league would start a monthly payment. Under the proposed scheme he would also be eligible for at least $1m and up to $1.5m. The letter stated that the AFL’s compensation scheme was set to launch in early 2023.

The legal letter also made it clear that the AFL was not stating that his football career caused his brain damage; rather that the compensation was made in a beneficial scheme without the need to prove causation.

While the monthly payments set out by Gordon Legal have been made, Kellett has never seen the promised $1m to $1.5m.

In March last year Kellett’s long-time partner Ms Rudolph said the AFL lacked “integrity, morals and ethics” for repeatedly delaying a promised injury payout. They had since become involved in a tangle of legal letters “that went nowhere”.

Finally in June last year, through Ms Rudoph’s efforts, they were able to secure a meeting at AFL House. Kellett’s parents were also in attendance.

Ms Rudolph said the meeting was “really emotional”.

“It was a chance to really humanise what Nige and people like him are going through,” she said.

The AFL “heard from his parents Doug and Coral, talking about Nige as a young player and how he would be a guest speaker at rotary clubs, holding the attention of a room and now … he can barely string a sentence together.

“His father Doug also spoke about Nigel having a secondary role with the AFL as an official AFL ambassador back in his playing days where he was a role model travelling regional Victoria to schools, charities and other events. He gave a lot to the wider AFL community.”

Ms Rudolph felt the meeting went well. Although nothing was promised, she thought something would come of it. Instead, she said, they were “ghosted”.

Ms Rudolph, who has quit her job to care for her husband and spend time with him, praised the efforts of the AFL Players Association “in trying to pull something together and for their recent free health check services initiative for past players”, but said the AFL hierarchy had failed them.

“It feels like they’re waiting for the past player TBI concussion list to shrink so the problem goes away, given all of the excuses and delay tactics that have been used,” Ms Rudolph said.

“The AFL have all the time but Nige and I are on borrowed time. Money is not going to buy a new brain for Nige but at the end of the day he was promised compassion and care. This is not about anyone personally – but where is their integrity? They are supposed to be a charity. Any other corporation would be held to account.”

If you know more, contact jessica.halloran@news.com.au or rices@theaustralian.com.au

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout