Circular cars aim to reduce, reuse, recycle and repeat

With car companies looking to the cut the carbon, vehicles are being designed to have as small an environment footprint as possible.

Buying an electric vehicle that produces zero emissions at the tailpipe, because it doesn’t have one, is a move plenty of people are considering as a way of reducing their carbon footprint.

The fact is, of course, that the amounts of energy put into producing and constructing any new vehicle, regardless of its motive force, are still significant, and that many of the parts and materials used either aren’t recycled, or simply can’t be.

While lead-acid batteries used in traditional cars are widely recycled, the lithium-ion batteries that power electric vehicles are particularly difficult to recycle, and contain raw materials including cobalt, lithium and nickel.

The answer to the challenges of reducing the emissions associated with the vast motor-vehicle industry is best described as a circle, or a closed circular economy, in which the goal is to “reduce, reuse and recycle” – not just with batteries, but every possible element.

Some car designers are even working on the idea of “perpetual mobility pods”, where as many parts as possible – from doors to wheels to panels – can be popped off, replaced and recycled.

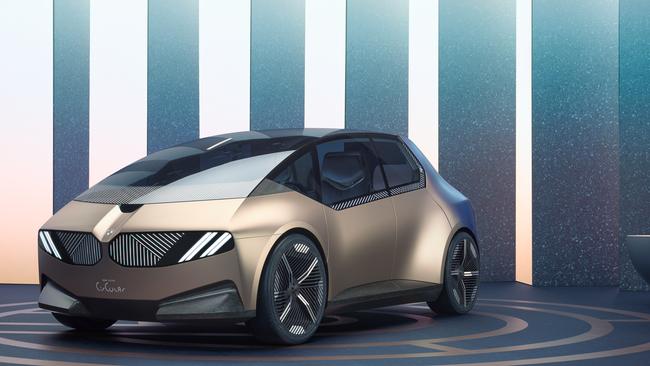

The most radical example of this is BMW’s recently unveiled i Vision Circular, a 100 per cent recyclable concept car that uses no paint, minimal amounts of glue – to make disassembly easier for recycling – and no badges. Even the seat upholstery, which is made with recycled plastics, can be removed and replaced, and the steering wheel is 3-D printed out of wood dust.

BMW’s design chief, Domagoj Dukec, who’s particularly proud of the anodised aluminium surfaces, which don’t need painting and have logos engraved into them instead of sticking on plastic badges, says: “This car has 80 per cent fewer parts than most, but it offers more.”

This Circular concept is a long way from being production ready, which is why it also uses a theoretical solid-state battery (which no one has yet offered in a production car) that BMW says can be fully recycled.

Volkswagen is working on finding ways to recycle current lithium-ion batteries and has stated that, thanks to hydrometallurgy, it should be possible to recover up to 95 per cent of the materials that make up the cells.

The hydrometallurgy process consists of deconstructing a battery, removing and crushing the modules and extracting the liquid electrolyte. Once the granules of lithium, nickel, manganese, cobalt and graphite have dried, “aqueous solutions” are used to separate the different metals, which can then be reused to manufacture new cells.

VW Group’s first recycling plant, in Salzgitter, Germany, is already in operation and Volkswagen chief executive Ralf Brandstatter says his company is on the “Way to Zero”.

“In the future, employees, customers and investors will give preference to those companies which place their social and environmental responsibility at the heart of their business,” Brandstatter explains. “Sustainability will thus become a crucial factor in corporate success. We’re taking a holistic approach to decarbonisation: from production through service life to recycling.”

The World Economic Forum has established a Global Battery Alliance (GBA), which is a public-private collaboration combining 70 organisations with a goal of creating a “circular battery value chain”, which it believes is key to meeting the Paris Climate Agreement’s goals for the transport and power sectors.

The GBA estimates that battery use could enable 30 per cent of the required cuts in carbon emissions in those two industries and provide 600 million people with access to electricity and create 10 million sustainable jobs worldwide by 2030.

Re-using EV batteries to provide access to electricity in disadvantaged areas was the purpose of a “solar nanogrid” established in Uttar Pradesh in India, where regular, hours-long power outages make life difficult, particularly for small businesses.

Created by German-Indian start-up Nunam, it re-purposes two Audi e-tron batteries previously used in test vehicles to provide power to about 50 shopkeepers and small businesses so they can keep working at night.

“Second-life batteries offer immense opportunities for greater sustainability, especially if they are powered by green electricity,” says Prodip Chatterjee, Nunam’s co-founder. “We prevent the premature recycling of intact battery modules while ensuring that people can get cheap access to electricity.”

A more immediate re-use for EV batteries can be found in Audi’s charging hubs, which are set to be rolled out this year across Germany.

Conceived as the First Class lounge version of an all-electric service station, the charging hubs offer high-speed charging downstairs and a lounge area upstairs to provide “an attractive, premium place to pass the time” while you recharge.

The hubs are built using flexible container cubes, which house charging pillars and “second-life” lithium-ion batteries – sourced from Audi’s own EVs. Because those batteries are forming the storage for the hubs, it makes complex infrastructure, such as high-voltage lines and expensive transformers, unnecessary. And that means the Audi hubs can be transported, installed and adapted to different locations.

“A flexible high-performing HPC (high-power charging) charging park like this does not require much from the local electricity grid and uses a sustainable battery concept,” says Oliver Hoffmann, Audi’s head of technical development.

“Our customers benefit in numerous ways: from the ability to make exclusive reservations, a lounge area and short waiting times thanks to high-performance charging.”