Venus discovery turns the tables on Mars as a life force

The discovery of phosphine in the air of Venus is our first solid lead that Elon Musk and the other space cadets might be heading the wrong way.

Either there has been a premature “false positive” diagnosis, or our nearest planetary neighbour has the same infection that we do, and just up the road towards the sun: life.

Yet this remarkable news, courtesy of astronomy professor Jane Greaves and her team at Cardiff University, has received much less attention here than our day-to-day battle with an unwelcome homegrown life form.

This isn’t exactly surprising. We have become so inured to the idea of alien life, via the likes of Star Wars, Star Trek and Doctor Who, that when it turns out real living creatures finally may have been found on a nearby planet it’s little more than a curiosity in the era of COVID-19 updates.

This is despite the fact if it turns out that the discovery of phosphine — a molecule that, as far as we know, can be created only by living things — actually does mean there is life floating high in the atmosphere of Venus, well, everything has changed.

It would have tectonic implications for biology, astronomy, philosophy, religion — the whole box and dice. But we are human. Even if it turns out that there are bugs on Venus — real live ones — hey, it’ll all blow over in a week or so.

And anyway, we’ve been vaccinated against this story for centuries. The Greeks and Romans revelled in myths of gods vying for the favours of Venus — the brightest thing in the sky after the sun and the moon. The goddess of love. Every culture has found her astonishing, the celestial torch.

In the 19th century, when it became clear that Venus was the same size as Earth but closer to the sun and shrouded in clouds, it generally was thought that the place was probably a tropical paradise (or steaming Jurassic jungle, take your pick).

By the time luridly illustrated science fiction shudder-pulp mags had emerged in the 1930s, the place almost certainly was populated by everything from radioactive dinosaurs to gorgeous large-breasted Amazonian warrior women who ate gormless male Earthling astronauts for breakfast. All these horrific/erotic fantasies sadly were burned to ashes in the early 1960s, when the Mariner and Venera (US and Soviet) probes established that large-breasted, laser-wielding lesbians riding shotgun on stegosaurs would be unlikely to survive a surface temperature of more than 400C and an atmospheric pressure 90 times that of Earth.

Venus, it turned out, was horrible. The dismayed magazine illustrators turned to drawing sexy dinosaurs from Alpha Centauri. Or Mars. Anyway, after finding out that Venus was a blast furnace, if there was going to be life anywhere nearby surely it would be on Mars, and billions of dollars have been spent on the basis of this optimistic assumption.

There is, of course, no evidence whatsoever of life on Mars as yet, but hey, it’s almost like Earth. A bit; it has 24-hour day (or close enough — Venus rotates every 243 days). And Mars has seasons. Ice caps. Relics of what might have been lakes or river deltas from a billion or so years ago. Beats Venus all ends up.

Indeed, Elon Musk wants us all to move there, despite it having almost no atmosphere, no water, and regularly chilling to minus 120C when the sun goes down. Death Valley on ice, anyone?

But things changed last week.

It turns out that spectrographic analysis of the atmosphere of Venus is not an easy thing to do, but if you can get the same result from two instruments you may be on the right track.

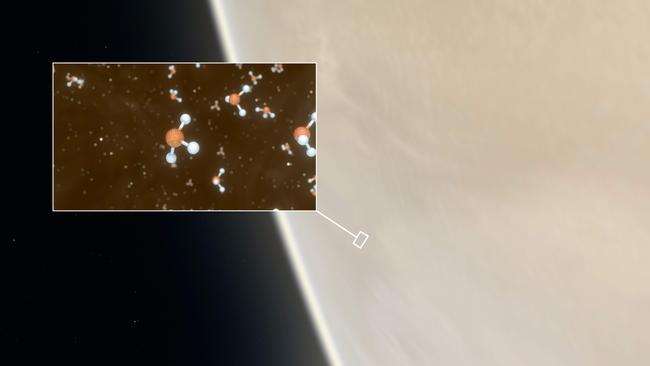

Phosphine? I’d never heard of it either, and it turns out to be horrible stuff, highly toxic to the likes of you and me. Its formula is PH3, or one atom of phosphorous attached to three of hydrogen. It smells like rotting fish.

But phosphine is, as far as we know, and much like rotting fish, created only by biological chemistry. It isn’t coming from a rumbling Venusian volcano or inorganic reactions in the atmosphere, which is almost entirely carbon dioxide with a ghastly stench of sulphuric acid.

But Greaves has found this stuff at more than 10,000 times the concentration that might be expected in a lifeless environment and her observations have been confirmed by others.

The key thing here is that, like methane on Earth, phosphine doesn’t last in an atmosphere without life continuously creating it. If all the cows stopped burping and we stopped opening gas wells, all the methane in the Earth’s air would be gone in less than 500 years. Phosphine is similar — it needs a constant source of generation or it falls apart.

If the new measurements are right and the chemistry stacks up, what we’re looking at here is possibly the most astonishing discovery in astrobiology, ever, if only because there haven’t been any others. But just think about it for a moment: life. Floating tens of kilometres above a blazing furnace in the poisonous atmosphere of the planet just next door.

How? What does it mean? Is it astonishing? Inevitable? Do we even care?

Creatures swimming in oceans under the ice of the moons of Jupiter or Saturn. A fossil bacterium in a Martian rock. Maybe they are there. But no sign as yet.

But this — phosphine in the air of Venus? It’s our first solid lead, as the cops would say. Sure, the SF magazines are long gone, along with their sexy warrior women and lithium lizards. But it must annoy the hell out of the Chinese, NASA and the European space cadets, all of whom have craft on their way to Mars right now, only to think that maybe, just maybe, they’re heading the wrong way.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout