Pushing the boundaries: seconds to fix a heart, by remote control

Only a handful of cardiologists are skilled enough to manipulate a valve remotely from outside the body.

At 9.20 on an autumn morning at Brisbane’s Prince Charles Hospital, a hush falls over a cardiac operating theatre.

Nadeane Giles, 73, is on the table, and she is about to be placed into cardiac arrest.

“Pacing ready,” says cardiologist Karl Poon as scout nurse Jocelyn Gloria prepares to apply the pacemaker that will accelerate Ms Giles’s heart rate to beyond 180 beats per minute.

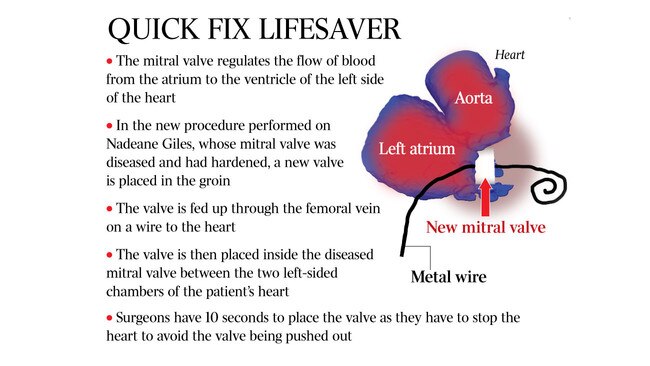

As her heart rate soars, Ms Giles’s heart soon stops. A crucial window of time opens up. The interventional cardiologists who are performing this operation — guided by X-ray and ultrasound — are about to place a new mitral valve they’re manipulating remotely on a wire inside Ms Giles’s existing diseased mitral valve that sits between the left-sided chambers of her heart. It’s the first time in Australia that this has been done without open-heart surgery. If the physicians get this wrong, there’s a high chance Ms Giles will die.

“It’s all down to 10 seconds,” says interventional cardiologist Karl Poon. “We have to stop the heart so the heart doesn’t move, otherwise the new valve will just be pushed out and we can’t anchor it.”

There are only a handful of interventional cardiologists in the country who are skilled enough to manipulate a valve remotely from outside the body to place a mitral valve into the heart with millimetre accuracy.

The mitral valve regulates the flow of blood from the atrium to the ventricle — the upper and lower chambers — of the left side of the heart.

The leaflets inside Ms Giles’s mitral valve, normally floppy and mobile to allow blood freely through, had virtually turned to stone. They had become calcified over many years, possibly as the result of childhood infection.

Three heart surgeons had refused to operate. Open-heart surgery was too great a risk. In a younger patient, placing a balloon inside the valve could be an option.

But Ms Giles’s mitral valve was too diseased. If a surgeon tried to decalcify it, her heart might literally fall in their hands.

“You can’t just cut everything out,” Dr Poon says. “She was between a rock and a hard place.”

Ms Giles’s daily life had become an agony. “I was told I had about 12 months,” she says. “I dreaded even getting into the shower. I had no energy, I couldn’t do my shopping, I could no longer drive, I was totally reliant on my husband. And I couldn’t breathe. It got to the point where I thought it was going to be my last breath. It was a shocking experience when you feel you just cannot get another breath in.”

Shortly before her operation, Ms Giles was admitted to hospital with pneumonia and a collapsed lung. As his patient deteriorated, Dr Poon began doing some research. He knew that interventional cardiologists in the US had pioneered a new procedure. They’d been replacing the mitral valve inside diseased valves in patients who had never had open-heart surgery.

Mitral valve replacements have been performed before by cardiac surgeons where a new valve is put within a pre-existing valve replacement via open-heart surgery usually. But it’s never been done before where a new valve is placed inside a native diseased valve through the groin.

Transcatheter aortic valve implantation is a method that had become standard practice for replacing diseased aortic valves for some patients — inserting a new valve in the groin and then threading it on a wire through a femoral vein up to the heart. But the mitral valve is much trickier. “The aortic valve is a much simpler structure,” says Dr Poon. “The mitral valve is much more complex. There’s different sizes and the shape of the valve is much more variable.”

Prince Charles Hospital interventional cardiologist Dale Murdoch, who operated on Ms Giles alongside Dr Poon, says mitral valve intervention is “about 10 years behind aortic valve intervention”.

“The valve is not in a single plane,” Dr Murdoch says. “So as well as being a D-shaped or a moon-shaped opening, it’s also got a saddle shape to it. So putting a single new circular valve inside a diseased mitral valve was really heresy a few short years ago.”

Advancements in medical device technology, imaging analysis and 3D printing have now made mitral valve intervention a possibility. The original plan was for a cardiologist from the US to travel to Australia to train cardiologists here. But the plan proved impossible, and so Dr Poon and Dr Murdoch had to have video- conferences with colleagues overseas, and perform the first mitral valve replacement in Australia without open-heart surgery themselves.

“Nadeane’s valve was getting tighter and tighter and she was getting more and more short of breath,” Dr Poon says. “It was really a perfect storm and we had to take her case.”

On that autumn morning, the scout nurse declares “pacing on” as Dr Poon prepares to place the new mitral valve inside Ms Giles’s heart.

The physician has already pushed the valve via a piece of wire up through her groin to the heart. He’s threaded a needle through each chamber of the heart, making a hole through which the new valve is pushed. As Ms Giles’s heart is stopped, he needs to place the new mitral valve with pinpoint accuracy. “Keep going, keep going, all the way down,” Dr Poon says as he keeps his eye on the X-ray of Ms Giles’s heart.

Three-dimensional ultrasound images also guide his way. The new valve is squashed into a cylinder, which allows it to be threaded through the hole that’s been pierced through Ms Giles’s two heart chambers. The valve device contains a balloon. At the critical moment, the balloon is inflated to expand the new valve, which is then anchored inside Ms Giles’s own calcified valve.

“It’s a notoriously difficult procedure,” Dr Murdoch says. “We use the calcified valve to tell us where to put the new valve but it’s very difficult to see. You also have to do it around a 180-degree bend. If you push the valve too far into the heart it can embolise and travel away from where it needs to be and be bouncing around. That’s a really bad day at the office. If you position it too far the other way it can travel in the opposite direction, and you can have a leak around the outside of the valve frame, which is a disaster.”

Immediately after the new mitral valve is placed inside Ms Giles’s heart, the surgeons hold their breath.

“You can actually observe the heart wake up in front of your eyes,” Dr Poon says. “We could see straight away that the valve was seated exactly where we wanted it. The heart was immediately in a much happier place. All the numbers and pressures came down immediately. I think I said ‘we nailed it’. It was true elation.”

Now that the procedure has been pioneered in Australia, it will open the way for other patients who are too high-risk for open-heart surgery to be given a chance at life. “I have seven or eight patients waiting for this procedure and that’s just one cardiologist,” says Dr Poon.

Ms Giles will never forget the look on her doctor’s face as he told her the operation had been a success as she lay in bed recovering. “He was grinning from ear to ear,” she says. “And for me, I feel wonderful now. I’ve got a second chance. You grab it with both hands. To have your life back, it’s indescribable. I’ll be grateful to Dr Poon forever.”