Is there an upper limit on the human lifespan?

Advances in medicine and technology mean we live longer, but ageing is part of our DNA.

First the good news. People are living longer than ever and, as Australians, we are near the top of the league table internationally for life expectancy. Many more of us will be seeing our ninth decade and beyond.

A girl born today can count on living for 85.2 years, a boy for 81.3 years. By 2063, average life expectancy will increase by five years in a big Australia of 40 million people, according to the government’s recent Intergenerational Report. This means nearly a quarter of the population will be aged 65 or over.

So here’s the catch. While life expectancy has more than doubled in the past century – in line with advances in medicine and technology, rising living standards as well as lifestyle choices such as reduced tobacco use – the ceiling on how long we can live has remained stubbornly fixed.

There may be more 100-plus centenarians and super-centenarians over 110 among us, but there we hit a very dead end. No Australian is known to have reached the milestone of 120; in fact, the only person who verifiably lived past that great age was Frenchwoman Jeanne Calment at 122 years and 164 days. She died in 1997.

This raises the question: is there a hard limit on the human lifespan? An expiration date set into our DNA that no amount of ingenuity can get around? Or can we aspire to rack up a Steve Smith-esque innings of 150, 200 or more? Could life expectancy ultimately be measured in centuries rather than decades?

Sadly, the scientific consensus is no. As an outer marker, age 120 may be as good as it gets. The human body has so many built-in redundancies that it seems to be hardwired at the genetic level to break down long before then. Ageing occurs because the mechanism of cell replication used by the body to grow and repair itself is imperfect: it happens each time with a slight variation, the minutest crack in the mirror.

Over time, the irregularities become more pronounced and a cell turns rogue. The off switch on mitosis – cellular duplication – is flipped to full throttle. Mutation piles upon mutation, corrupting more healthy cells, then clumps of tissue in the worst-case scenario of cancer. Writer Siddhartha Mukherjee, in The Emperor of All Maladies, his award-winning biography of the disease, suggested it was nature’s way of calling time on people – a case of God meets Gaia to ensure the planet isn’t overwhelmed by its apex predator.

A doctor will tell you that advancing age is the No.1 risk factor for cancer. So too for heart disease, still the biggest killer of men in this country. As the years roll on, reserves of regenerative stem cells diminish, mitochondria malfunction, bones thin, muscles waste away, organs fail, the immune system misfires and the brain can become clogged by plaque. Dementia is largely a disease of the elderly, and its increasing prevalence is another function of an ageing population.

A 2016 study published by the leading research journal Nature purported to demonstrate that human life reached its limit at 114.9 years, igniting a scientific firestorm. In 2018 the equally prestigious publication Science ran an authoritative rebuttal of the paper, arguing that longevity continued to increase and that a cap, if any, on how long people lived was yet to emerge.

Both sides of the argument agree that prolonging life as an end in itself is pointless; living well in old age is just as important as living longer. The national debate on this conundrum still has a long way to run. The Intergenerational Report released by Treasurer Jim Chalmers last August cast forward 40 years, to where the number of Australians aged 85 or over will have tripled and where the bill for their care will fall on fewer shoulders, with the share of the population of working age contracting.

Can we aspire to rack up a Steve Smith-esque innings of 150, 200 or more?

Longevity researcher Perminder Sachdev, a professor of neuropsychiatry at the University of NSW who led a study of 500 nonagenarians and centenarians in Sydney, said nature was replete with examples of species having a maximum lifespan, and this could well be the case with humans.

That’s it, then. Case settled.

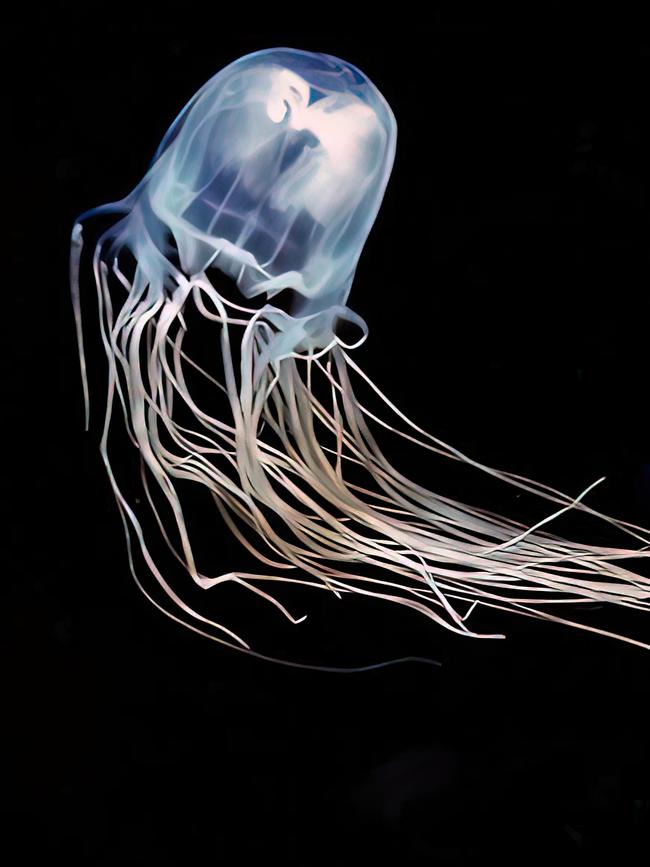

Well, not quite. He also points out there are exceptions to the rule, such as the immortal jellyfish, which when injured or threatened can revert to its juvenile state, mature and revert again – potentially forever. Individual microbes found in sediments deep beneath the sea floor are thought to have a metabolically active age of 100 million years or more.

The upshot is there are very few set rules when it comes to life expectancy between the species and any given organism. How long we can live, as opposed to the lottery of how a person will live, comes down to an interplay of complex genetic and biochemical processes that science is still coming to grips with.

But if he were to hazard an informed guess, Sachdev says it is unlikely there will be any great leap forward in terms of extending the maximum limit of human life: “Five years, maybe 10 years is a possibility, but I can’t see it going much beyond that.”

This assumes, of course, we are talking about the human genome as it is. Scientists have altered the DNA of a fruit fly to triple the insect’s lifespan, while experiments on laboratory mice have increased longevity by up to 50 per cent, Sachdev says.

In most countries, including Australia, such research would be illegal should it cross over into the human germline. While scientists can manipulate somatic cells – those in the body that have already differentiated into a specific tissue or blood type – gene editing a sperm, egg or fertilised embryo would propagate changes in every cell of the body and potentially cascade into future generations through the germline.

And that’s another story entirely …

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout