HIV cure hopes in landmark research

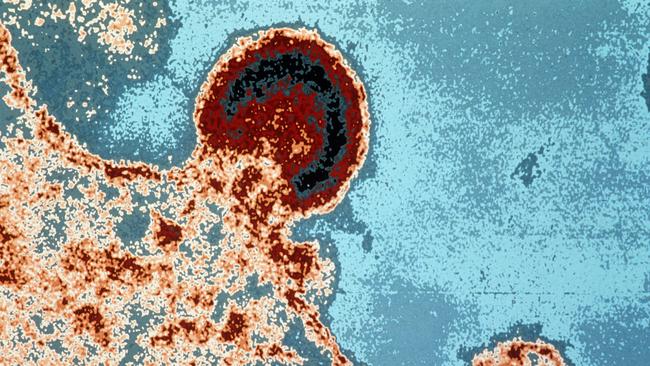

Scientists are a step closer to finding a cure for HIV, with a drug shown to reverse the ability for the virus to ‘hide’ inside the cells of people on antiretroviral therapy.

Scientists are a step closer to finding a cure for HIV, with a drug shown to reverse the ability for the virus to “hide” inside the cells of people on antiretroviral therapy.

Researchers from the Doherty Institute together with scientists at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle conducted the study on the effects of the drug pembrolizumab, a cancer immunotherapy treatment, finding that it was able to alter the function of the HIV “reservoir” where the virus lies latent inside cells.

Pembrolizumab is a monoclonal antibody that reverses the “exhaustion” of the immune system. When immune cells called killer T cells get “worn out” they express proteins on their surface, one of which is called PD1. The monoclonal antibodies, also referred to as anti-PD-1, work by blocking these exhaustion markers, allowing the killer T cells to regain function and kill cancer.

Scientists studied 32 people with cancer who were also living with HIV to see whether pembrolizumab would have the same effect in reversing the exhaustion of the immune system in HIV sufferers.

“What these drugs do in cancer is they rev up the immune response,” said Doherty Institute director Sharon Lewin. “We took the opportunity of studying people who were receiving anti-PD-1 for their cancers and also had HIV.”

Professor Lewin said the monoclonal antibody helped “reveal” the virus cells lying latent in people with HIV.

“PD-1 didn’t get rid of the reservoir,” she said. “But what it did was it exposed those hiding virus cells allowing the immune system to kill the cells. Therefore we think it would be part of a cure strategy.”

There are 37 million people worldwide living with HIV, and 1.8 million more people are infected every year.

Anti-retroviral therapies mean people with HIV can live normal lives, but so far a cure for the disease or a vaccine has eluded scientists. Curing patients of the disease is extremely difficult because the virus incorporates itself into the infected person’s DNA.

“The main strategy we are after with trying to cure people is get rid of that reservoir of virus,” Professor Lewin said. “To do that you have got to expose the virus cells first to the immune system, you’ve got to reveal those cells.

“In this study, we were able to show that in a cohort of 32 people who have cancer who are also living with HIV, pembrolizumab was able to perturb the HIV reservoir, which is a very exciting result and involved many groups around the world.”

The study enrolled participants in the US through the Cancer Immunotherapy Network based at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, and the clinical trial was led by Professor Thomas Uldrick, a medical oncologist and expert in cancer immunotherapy.

Blood from study participants was collected before and after treatment with pembrolizumab. The HIV virus was then interrogated by Professor Lewin’s team at the Doherty Institute and by collaborators at the University of Montreal and the National Cancer Institute in Frederick, Maryland.

Professor Lewin said she was optimistic that scientists would one day find a cure for HIV, and this latest research would help advance that cause. “I do think with a concerted scientific effort we will get there,” she said.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout