Energy + girl power = space-time enjoyment

Teaching Einstein’s view of the universe has led to a new generation of girls gravitating towards physics in a way even the smartest scientist couldn’t have predicted.

Teaching Einstein’s view of the universe has led to a new generation of girls gravitating towards physics in a way even the smartest scientist couldn’t have predicted.

Jyoti Kaur, an education researcher and physics major, discovered the link when she analysed the Einstein-First Project, an innovative program that she and her team use to introduce Einsteinian physics — curved space, warped time, photons, black holes and quantum entanglement — into primary and high schools across Perth.

The project did not set out to identify gender-specific trends but was aimed at testing students’ grasp of Einstein’s revolutionary concepts, with physics often considered too difficult to teach until young people reach university.

“We tested the students with questions like ‘what is time, or space or gravity?’”, Dr Kaur said.

A striking finding was that girls registered substantially lower engagement scores than their male classmates.

“We found that girls’ interest was initially very low compared with boys. Then after the program, we compared their responses and we found that the girls now had equal or more positive attitudes towards physics than the boys.”

She said it was exciting to learn they had closed the gender gap despite tackling difficult concepts. “I thought it was because I was a woman teaching girls, but then I looked at the outcome for male presenters in other classrooms and it was the same. We think it was the hands-on, collaborative nature of the program that suited the girls so well, not the Einsteinian concepts.”

Dr Kaur and her team are running the Einstein-First Project in 24 West Australian schools. The project, funded by a $1.5m Australian Research Grant, was initiated last year by the ARC Centre of Excellence for Gravitational Wave Discovery at the University of Western Australia.

All the lessons are based on simple group demonstrations, such as a space-time simulator set up in the classroom at Thornlie Senior High School “to demonstrate space is curved and gravity is curvature of space-time”.

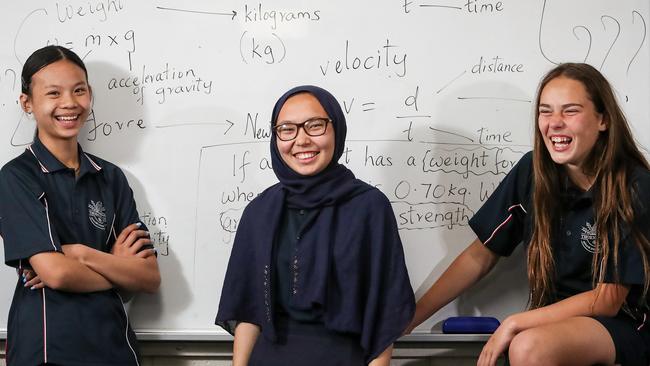

Students Sabira Faiyazi, 13, Nguyen Nguyen 12, and Mia Sutton, 13, used metal balls of different sizes to “warp” the stretched black surface. There was also role-playing in which a student played Einstein arguing with Isaac Newton that light consists of particles not waves.

The trio say they like studying science, but several female classmates who have not yet entered the program told The Australian that physics seemed “boring and too hard”.

Dr Kaur’s findings, published in the journal Physics Education, were based on 233 students, academically average and gifted boys and girls aged 11 to 16 years, at two Perth schools. Girls tested in a Year 10 class in Indonesia recorded the same improvements.

“We did not set out to make the program gender-friendly,” Dr Kaur said, “but the challenge of teaching a topic that many teachers think is too difficult for young people made us design classes that suited girls”. She said Einsteinian physics had tremendous applications in daily lives. “Students use modern gadgets like GPS everyday in their mobile phones, so we want to teach them the physics behind it.”

The project team, whose work has been adopted in seven other countries, is preparing an Einsteinian-based science curriculum for Australian schools to replace the current version they say is based on “obsolete” Newtonian science.

Thornlie science teacher Charlotte Rebello said she was looking forward to the impact on female students, who have rarely ranked with the boys until now in winning science awards.

“With this program I hope to fire up their passion and show them that physics is not just for boys,” she said.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout