Broken skull puts humans in Europe 150,000 years earlier

A skull unearthed in Greece may be the earliest evidence of modern humans outside Africa.

Two hundred and ten thousand years ago, a relatively hairless ape arrived at a limestone cave. Its ancestors had slowly been moving around the Mediterranean, hunting and foraging.

This cave system was different, however. Because with its back to the sea the ape was able to look north towards a continent untouched by humans. This ape was the first Homo sapiens to set foot in Europe — 150,000 years earlier than previously thought, according to an analysis of fragments of a fossilised Greek skull.

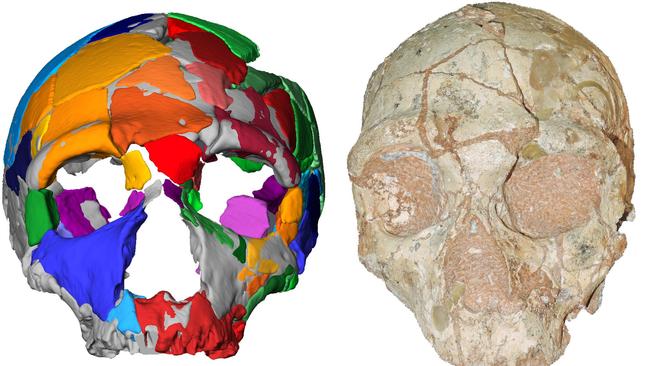

The skull, found in the southern Peleponnese and assumed to be Neanderthal, had lain almost unstudied for 40 years. When scientists tried to reconstruct it, they realised that it had the features of our species, Homo sapiens, yet dated from tens of thousands of years before humans were meant to have reached Europe.

“It’s extraordinary,” Katerina Harvati, from the University of Tubingen, Germany, said. “All our results point to the same conclusion. There are no features typical to the Neanderthal.” Instead, like our skulls, it is curved. “They show instead the presence of this modern human feature.”

In the past decade, genetic and archaeological findings have transformed our understanding of early humans, showing that until relatively recently Homo sapiens was one of many species of humans and that our ancestors ranged further and earlier than thought. Rather than congregating in the Rift Valley of Kenya, Tanzania and Ethiopia, before a single push out of Africa 60,000 years ago, finds from Morocco to Israel have provided evidence of a series of migrations, with Homo sapiens spreading out in waves.

Professor Harvati, whose research is published in Nature, thinks that her skull came from a human originally from modern Israel. “We did have documented dispersal in Israel. So it’s not so unimaginable that some of these populations would have occasionally expanded to reach Europe.”

She said that although today the cave system is arid, during ice ages it would have been attractive. “There would have been reasons for humans to have been drawn to [an] area where plants, animals, and humans could survive in a relatively mild climate.” And, with lower sea levels, a cave that backs onto the Mediterranean today would have overlooked flat, fertile, land. “It could have been a coastal plain, with good hunting and excellent game.”

Chris Stringer, from the Natural History Museum, said this was the first archaeological evidence of something suspected from genetic data — which showed Homo sapiens DNA in Neanderthal populations of Turkey and the Levant. The apparent confirmation raised “a range of questions and possibilities, including where they came from, and what happened to them”.

----------------------------------

ANALYSIS

Tom Whipple

The story of humans used to be simple. For hundreds of thousands of years we bided our time in Africa. We came down from the trees, we walked on two legs, we evolved bigger brains — until at last, 60,000 years ago, we were ready. Then, in a lightning-quick migration, our large craniums took us from continent to continent in their inevitable conquest of the world.

In a little over a decade, however, a series of findings have upended that tale, showing that the triumph of Homo sapiens was neither so simple nor so inevitable. The world was not an unpopulated prize to be taken. Other human species were living throughout it, and quite probably were our match. Neither were our forays inevitably successful. As the latest find shows, Homo sapiens sometimes gained footholds lasting thousands of years but were pushed back.

Why, then, did we succeed in that one great migration 60,000 years ago? Perhaps because one aspect of the original story was correct: that was when we were finally ready. Some scientists think it was only 60,000 years ago that our brains, rather than just our bodies, were ready to face the world out of Africa.

THE TIMES