Australia sleepwalking towards major ‘infertility trap’

Top reproductive biologist says Australia is chronically dependent on assisted conception therapies.

Australia has become chronically dependent on assisted conception therapies and failed to confront the dramatic decline in birthrates, says a reproductive biologist who is warning that advanced economies are sleepwalking towards a major fertility crisis.

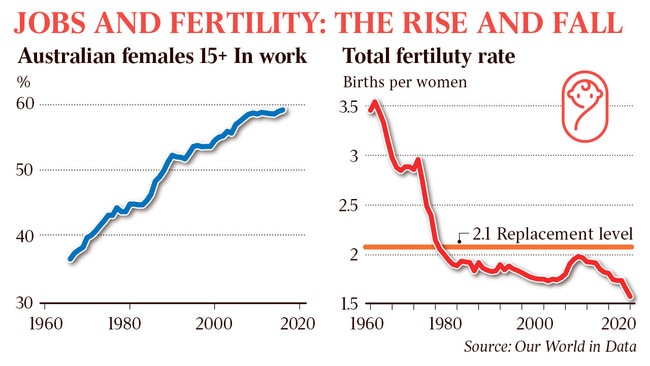

John Aitken, recognised as one of the world’s leading sperm biology and fertilisation experts, said Australia had become a “prime example” of a modern economy heading towards an “infertility trap”, with immigration policies used to artificially prop up the country’s population because of plummeting birthrates.

Professor Aitken, who will deliver Newcastle University’s Clarke Memorial Lecture on Tuesday, said global fertility rates have been in “relentless decline” since the 1960s and could eventually lead to the “uncontrolled descent of the human population” if urgent action is not taken.

“With the Industrial Revolution in the late 1700s, the world embarked on a new socio-economic journey which carried us into the modern industrialised 21st century, and there have been many good developments,” Professor Aitken said. “But now there are many factors associated with modern 21st-century living which are compromising female and male fertility.

“We need to wake up to our own biology.

“That can’t be changed. We need to change the social structures around it rather than trying to force the reverse.”

Professor Aitken said the short-term driver of the fertility crisis continued to be socio-educational, with women putting off having children until their early 30s and then relying on conception therapies into their 40s to fall pregnant.

“We have witnessed the rising tide of female education, but the trouble is that as women become more educated and enter the workforce, there is naturally not the same impetus to have children,” he said.

“They have been forced to choose between pursuing a career and having children … This is a 21st-century tragedy,” he said.

In Australia, some 20,000 women in their early 40s undertake IVF therapy each year, with less than 5 per cent successfully falling pregnant.

“We can do many things in modern industrialised society, but the one thing we cannot do is change our biology because we stop reproducing in mid-life,” Professor Aitken said. “People are just leaving it too late to have their families and the average age of women in IVF clinics is about 37, and the tragedy is this cannot rescue age-dependent infertility for women.”

Professor Aitken said a possible solution would be more generous parental leave schemes or a Scandinavian-style model that encouraged women to have children earlier rather than sacrifice their careers.

Infertility among males remains as ominous, he said, with the forces fuelling the decline in male fertility also contributing to the rise in reproductive cancers such as testicular cancer.

“The rise of environmental pollution, including contaminated plastics, over the past 50 years has played an enormous impact on male fertility and we’ve seen a startling decline in sperm counts that are roughly half what they were five decades ago,” Professor Aitken said.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout