Australia behind curve on slowing rate of coronavirus infection

Australia is struggling to ‘flatten the curve’ of coronavirus infections across the nation.

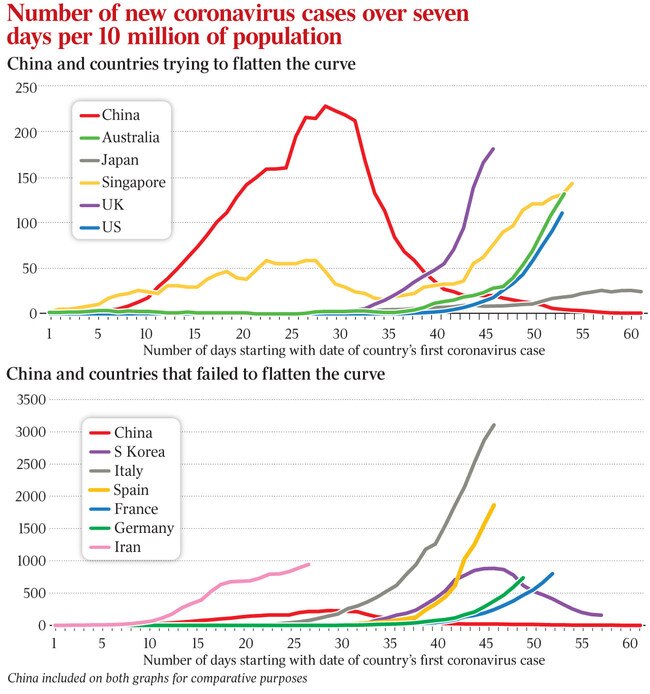

Australia is struggling to “flatten the curve” of coronavirus infections across the nation with an increase in the number of cases exceeding a disturbing rise in the US on a per capita basis, health authorities have warned.

With NSW a “hotspot” compared with other states for the infection’s spread, government and medical officials expressed concern on Tuesday that the number of cases would continue to increase significantly following the largest jump in a 24-hour period since tallying began.

The national total jumped from 375 to 440 confirmed cases, including five deaths. NSW recorded the biggest increase in a single day from 170 to 210 cases, followed by Victoria, up from 71 to 94.

Outbreak levels in other states and territories appeared to remain relatively static, although health experts say the true picture of the virus’s spread may not be known until testing is more widespread. They urged better availability of testing kits and the introduction of more accurate blood tests in place of throat swabs as soon as possible.

Australia ranks at close to 20th in the world for its national tally of cases, still far behind those in other nations reporting them in the many thousands, but the challenge for health authorities, despite the government’s introduction of strict self-isolation for all inbound international travellers and limits on mass gatherings, remains how to stem the current rate, where numbers are doubling every six to seven days.

Raina MacIntyre, head of biosecurity at the University of NSW, said Australia obviously had a much smaller population than the US but the rates of transmission were very similar at this early stage of the virus spread, and NSW was the nation’s “hotspot”.

Professor MacIntyre said Australia had “performed very well” in trying to slow the virus spread by imposing the right measures throughout the population in city and remote areas but it was concerning that the rise of cases in Australia, based on population size, was tracking almost the same as the US, where there had been reported difficulties related to shortages of equipment and fears about health workers becoming infected and transmitting the disease to family members and others, forcing their removal from frontline care.

By comparison, stronger control measures in Japan and South Korea had led to some success in “flattening the curve” of infection with a slowing of the virus’s spread after those two countries experienced some of the biggest initial reported diagnosed cases.

Italy and Iran continued to suffer the worst numbers per capita, although the rate for new cases and deaths was also rising at disturbing levels in Spain, Germany and France.

“We’re still in the upward swing of cases in Australia, and the strategy has to be about trying to make the number peak early, and make the peak smaller,” Professor MacIntyre said. “It’s a critical time — we have to act early; the number of cases is doubling every week.”

At the current rate, Australia could have more than 10,000 diagnosed cases in less than six weeks, unless the spread is slowed.

With the death rate estimated at 1 per cent for those diagnosed in Australia but much higher for older people with underlying health conditions and weakened immunity, the government is preparing for a worst-case scenario of 150,000 fatalities if 60 per cent of the population becomes infected.

Under the best-case scenario of 20 per cent infection, the nation would still have 50,000 deaths out of the five million people infected with COVID-19.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout