The Teacher’s Pet: family dares to dream torment is over

For almost 37 years, Lyn Dawson has been missing. Were you to talk to her family, they’d have said: we’d rather know.

Missing. For almost 37 years, Lyn Dawson has been missing, and were you at any point to have talked to her family, they’d have told you: we’d rather just know.

Whatever happened, however bad, whatever it is, we’d just rather know. Because the not knowing? It’s torture. Day and night, Lyn’s brother, Lyn’s sister, for a long time her mum and dad, lived with minds savaged by the darkest thoughts, the most terrible nightmares.

Is she dead? If so, did she suffer? If so, did she know the end was coming and was it painful?

Stop. You just want it to stop.

But you can’t, because she’s still missing, and there are so many unanswered questions. Did somebody take her life, and if so, who? And were her last thoughts of her children, for whom the whole passage of life has been unimaginably difficult?

Consider their circumstances. Their mum disappeared and for years nobody talked about it. Dad said he didn’t know, apparently she just left them, and then before they could even process that, his new girlfriend was moving in, and all they could do was try to absorb it somehow.

And for years they did, and for everyone in the family, for years, this not knowing has been torture.

And then, into this picture, walks a gentle giant.

Hedley Thomas has no idea I’m writing this, and I’m not going to tell him, because he wouldn’t let me do it, but he’s at once an enormous person, with a heart the size of his carriage. And were you to ask him, he’d tell you that a few years back he was just about done.

That’s a bit of this story that’s still untold: the re-examination of Lyn’s disappearance, the story that became the record-breaking The Teacher’s Pet podcast, came just as Hedley was starting to think about what to do with the rest of his life.

He’d been a journalist for more than 30 years, and he’s arguably the nation’s best, having won the Sir Keith Murdoch Award, the Gold Walkley, four other Walkleys … really, he’d done all you can do, including being shot at by enemies made in the course of fulfilling professional duties.

Plus some dopes had tried to drag his good name through the mud for pursuing stories they’d rather he didn’t.

This can be a grubby game, too.

He left the profession for a while, found no satisfaction, came back, tried again to get his teeth into a few things, and he was, he admits, struggling to find motivation. And then this story. He always remembered this story.

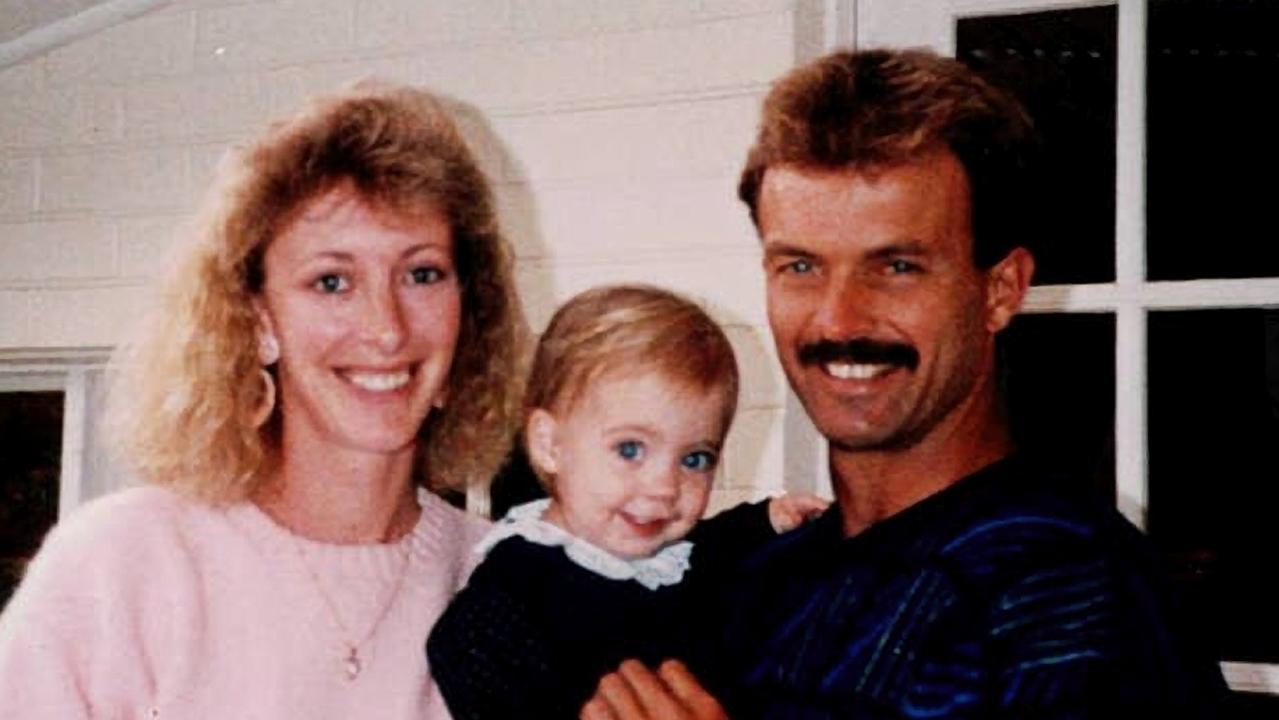

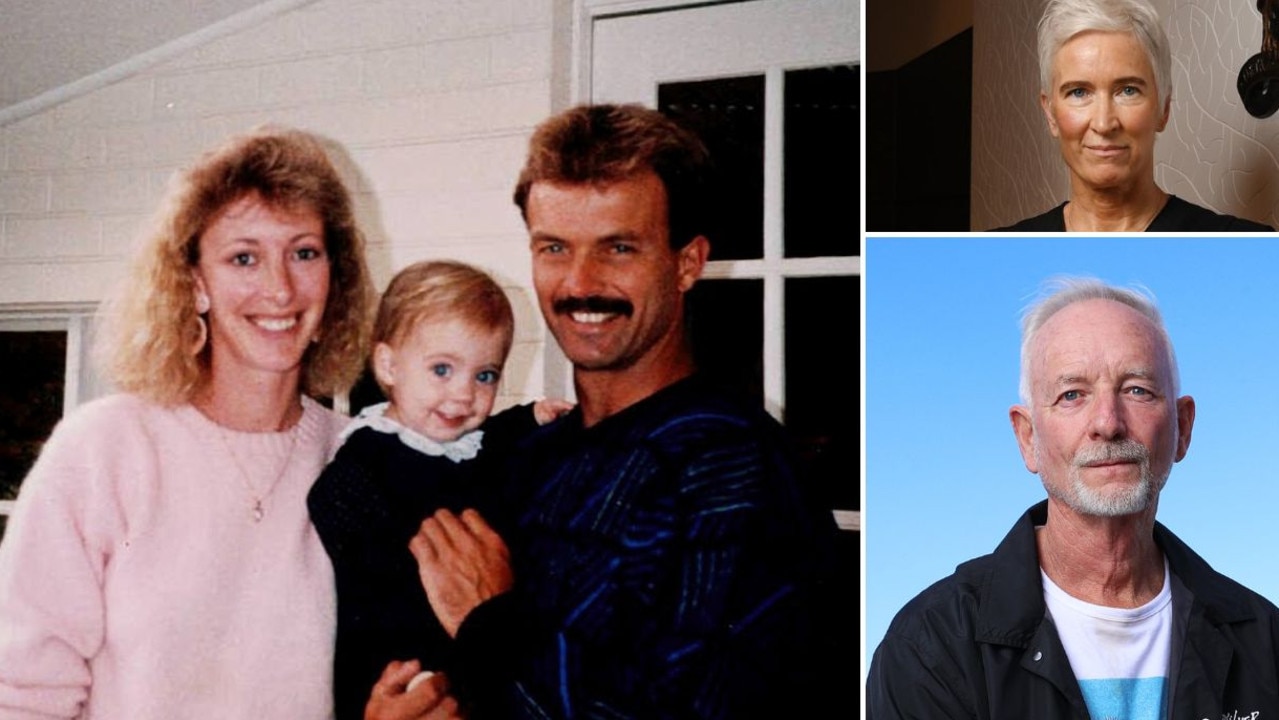

The tale of twin brothers — golden-haired and good-looking — one of whom was missing a wife. Chris Dawson, a PE teacher, had been having sex with 16-year-old Cromer High School student Joanne Curtis.

He’d asked his wife, Lyn Dawson, to take her in, saying she was from a troubled background.

A tearful Lyn had refused. She wanted to save her marriage, and they went to counselling, but then on January 9, 1982, Lyn was due to meet her mother at the Northbridge Baths in Sydney when she disappeared. Two days later, Chris moved his young lover into his home, and into their bed.

This, then, was Hedley’s unfinished business, the story he couldn’t shake, the one that still gave him sleepless nights, and now his kids were growing up, he had time on his hands, and that was pretty much all he had.

Certainly he had no great contacts, no inside running — just a quiet manner, a great deal of patience, and a willingness to listen. Hedley might have written a series of stories for this newspaper — he did that — but decided also to grapple with a new medium, the podcast, just as the true-crime genre was exploding in popularity.

Journalism has in recent years been replaced in so many instances by opinion, by commentary and by twits on Twitter.

But readers out there — listeners, too — are still hungry for good stories, and in particular crime stories set against familiar backgrounds, in this case mum, dad, two kids, a backyard pool and a public school.

And so he got to work. Others quickly joined Hedley in his efforts, among them Slade Gibson, with whom he won the Gold Walkley last month — Hedley’s second — and then came Queensland’s best crime reporter, David Murray, and others.

Together, this team found things that had not previously been unearthed. They talked to people who hadn’t previously said what they wanted to say.

It was sustained, it was forensic, and it was disciplined. At times they also ran only on passion, sometimes on adrenaline, and sometimes without it, because of the energy-sapping nature of an investigation over six weeks, then six months, then a year. You’re always conscious that it may go nowhere and you have to keep believing that what you’re doing is worthwhile. That people care.

They made one episode after another, and it was catching on — one million downloads, then 10 million, then 27 million, making it the biggest podcast in the world. There were difficult moments, such as in September when police decided to dig for Lyn at the former Dawson family home on Sydney’s northern beaches.

The family had hearts in mouths. What if they found something? How would it feel to have Lyn’s bones, her skull, excavated from under the broken edge of the pool where the children had grown up playing?

On the other hand, what if they didn’t, just as Chris had always insisted they wouldn’t?

The search came up empty, but on Hedley went, and some listeners, and some readers — you can’t blame them — could be seen joking on commentary boards about how they seemed at times to be stringing it out, with some episodes definitely more flabby than others. Look how they had been reduced to talking — this is apocryphal — to the sister of the cousin of a kid whose brother went to that school, just to keep the series going.

But, actually, that’s what you have to do. You have to keep making the podcast, and you have to keep making the paper, because otherwise, it’s all for naught.

And so The Teacher’s Pet podcast started again, with new episodes, and The Australian had only published two of them when suddenly yesterday a development had everyone’s phones exploding into life.

There had been an arrest. They had arrested him.

Lyn’s sister, Pat Jenkins, tells The Australian she was “out shopping and I didn’t have the radio on”. “I pulled into the driveway, came in the house, my son said: ‘Your phone’s been running hot.’

“I had barely put the bags down, somebody was knocking on the door, and it was the TV people. Then it was one crew after another, all the newspapers, everyone, and later I found out, police had been trying to call us, they did want to let us know, but the tape on the answering machine had filled up, or run out, or whatever it is you say.

“And it felt surreal, because what people forget is, until 1998, Lyn was still a missing person. And for a lot of that time, we were in the dark, trying to figure out what police were doing, what was going on, maybe even if anything was going on.

“And you feel blind, because in the beginning, we’d ring (the police) and they’d say, we can’t talk to you, you’re not the next of kin. Chris (Lyn’s husband) is the next of kin. Then he divorced her, and mum was the next of kin, and it was so difficult for mum. She never got across the idea she wouldn’t see Lyn again. ‘My Lyn’, she used to call her.”

Both Lyn’s parents died in 2001, the year of the first coronial inquiry into her death. There was a second inquiry. And now, without warning, Chris had been taken into custody, and what was Pat’s response to that?

“It’s oh, oh, oh, oh …”

For a second there, she couldn’t speak for shock.

Eventually she gasped: “Well, I’m just overwhelmed. Because they didn’t let us know. And I know, it has to be that way. They didn’t tell us until they were on his door step. That is the right way, but after 37 years, it’s just disbelief.”

Lyn’s family tree has deep roots and many branches, and it took some time for everyone to reach everyone else. Lyn’s brother, Greg, was also at home when he found out, and he had a bit of a cry with his wife.

Across town, a nephew, David, found himself staring at his phone screen, just shaking.

A second cousin, Allyson, who runs a “Find Lyn” Facebook page, was in a meeting at work when the phone pinged, and pinged again. And again. “It came out of the blue,” she tells The Australian, “and I felt scared, sort of strange. I’m mindful that we’re in territory we’ve never been in before. You never give up the idea that something will happen.”

Let’s be as frank as the police were yesterday: this development — the arrest — wouldn’t have happened without Hedley.

NSW Police Commissioner Mick Fuller made that plain yesterday, saying new statements from fresh witnesses had “helped pull pieces of the puzzle together”.

“These new statements came about as a result of media coverage,” he said.

And now, of course, everyone is constrained by the law of sub judice. This won’t be the case everyone’s talking about any more.

Chris Dawson has been taken into custody.

Detective Superintendent Scott Cook said in Queensland yesterday that Dawson had been “a little bit taken aback” when they arrived to arrest him.

He’s always protested his innocence, and his family stands staunchly behind him. In a statement, they said: “We have no doubt whatsoever that Chis will be found not guilty as he is innocent … There is clear and uncontested evidence that Lyn Dawson was alive long after she left Chris and their daughters.”

The evidence against him is entirely circumstantial. Nobody saw him murder Lyn. He’s always denied it, saying she called him on the day of her disappearance to say she needed some time to think, and since he’d been having an affair, and they’d been seeing a therapist, he had no reason to doubt that.

He says he never saw her again.

Now he stands accused of murder, with others to decide his fate, and this is right, and proper.

Journalists at good newspapers can give a story time, space, attention, but it is to the courts that we turn for justice, at the same time dedicating ourselves to two precious concepts: one, the presumption of innocence, which must be defended with all our might; and two, the power of journalism, which is not dead yet, not even close.