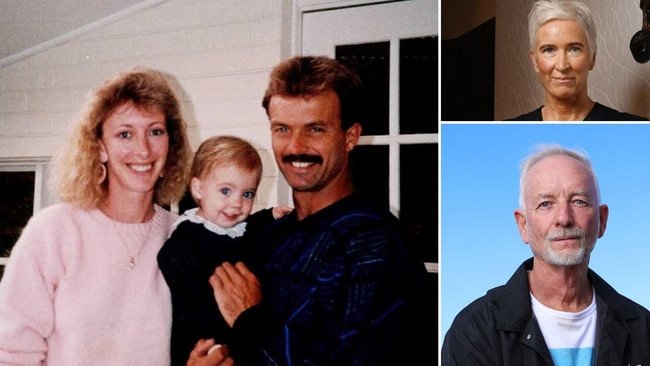

Bronwyn Winfield’s brother urges coroner to search a Sydney home for her body

Andy Read says the missing mother’s body ‘may well be located’ under concrete at a Sydney property | NEW EPISODE

The brother of missing mother Bronwyn Winfield has formally called on a coroner to launch investigations at a Sydney home where he says her remains or other evidence “may well be located”.

Andy Read’s 12-page letter to NSW Coroner Teresa O’Sullivan, detailing reasons to suspect Bronwyn’s remains are entombed under concrete at the house, is revealed in Friday’s return of The Australian’s investigative podcast series Bronwyn.

Bronwyn’s estranged husband, Jon Winfield, worked as a bricklayer on the Illawong property in southern Sydney immediately before and after she went missing from Lennox Head on the state’s far north coast almost 32 years ago.

“I am writing to you to respectfully request that you issue a coronial investigation scene order … in respect of a property in Illawong, NSW, where I believe Bronwyn’s remains or other potentially incriminating evidence may well be located,” Mr Read’s letter states.

“There is a strong public interest in confirming whether Bronwyn’s remains or other potentially incriminating evidence have been concealed at (the house). Knowing this would provide some comfort to her family and friends.”

The letter was prepared with the help of lawyer and avid podcast follower Karina Berger, who worked with the Australian Government Solicitor for 17 years until mid-2024.

It outlines key information about Bronwyn’s disappearance and suspected murder, including new developments associated with the podcast.

Ms Berger has substantial experience in coronial investigations and inquest work and has been assisting the podcast.

Coroners have special powers to grant police and others access to sites to perform any examinations they believe necessary.

“I imagine that what might be required could include conducting scans of some of the concrete/ground at the property, drilling into the concrete/ground and using a cadaver dog in certain areas, before any more fulsome investigation was undertaken,” Mr Read’s letter states.

“I am acutely aware this would be an intrusion for occupants of the property.

“However, I do not consider this would be a significant intrusion and I consider public interest favours these investigations being conducted.”

Mr Winfield, who turned 70 this week, has always emphatically denied any involvement in the disappearance.

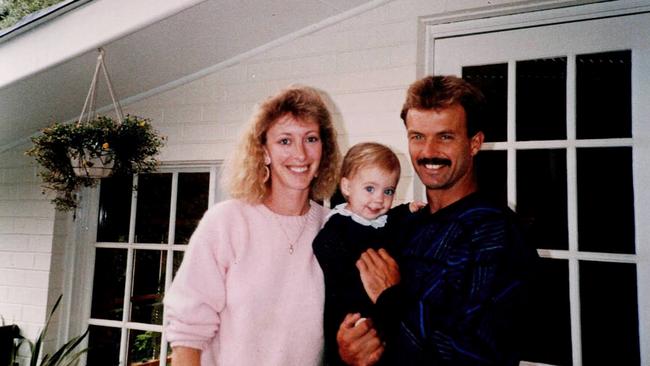

He was working on construction of a house at the Illawong property when he heard Bronwyn, then 31, and her two daughters had moved back into the family home in Lennox Head.

Bronwyn, who had previously moved out with the girls when the marriage broke down, used a locksmith to regain entry after Mr Winfield changed the locks.

On the evening of May 16, 1993, Mr Winfield returned to the Lennox Head home after flying from Sydney to Ballina, and Bronwyn was never seen or heard from again.

He has said she was picked up in a car after suddenly saying she needed some time away.

Later that night, Mr Winfield drove to Sydney with Lauren, 5, his daughter with Bronwyn, and Chrystal, 10, Bronwyn’s daughter from a previous relationship.

Mr Read’s letter to the coroner details Mr Winfield’s “unusual movements” including his hasty trip from Sydney to Lennox Head and immediate return with the two girls. “The trip was unplanned. Being mid-May, it was not school holidays, and the girls were supposed to be attending school,” the letter says.

The next morning, on May 17, 1993, Mr Winfield turned up at his former wife Jennifer Mason’s home at Caringbah in southern Sydney.

Ms Mason wasn’t home, so he asked her mother-in-law, Joan Mason, whom he had never met, to look after the two little girls, still dressed in their pyjamas.

“I, and others in the podcast team, consider this was extremely strange behaviour on Jon’s part. The 2 girls did not know Joan Mason. Jon had other childminding options available to him in Sydney, including me and my wife (at Caringbah), and Jon’s brother and his wife (Peter and Louise Winfield, at Engadine),” Mr Read told the coroner.

In 1998 in his only recorded police interview, Mr Winfield did not disclose leaving the girls with a stranger for several hours, “possibly so as not to arouse suspicion about his movements”, the letter adds.

To Mr Read’s knowledge, Mr Winfield had never accounted for where he was between leaving the girls that morning and registering the family car at neighbouring suburb Miranda at 3.07pm.

Mr Winfield then collected the girls from Ms Mason’s house and arrived at Mr Read’s home about 4pm.

“This means Jon had the opportunity to dispose of Bronwyn’s remains during this period of time,” Mr Read states.

Family members were told by Mr Winfield that he had returned to Sydney for urgent work on a big job.

Mr Winfield did not say this to police, potentially because “any disclosure of it may have alerted them to his connection with, and ability to access, the Illawong property”.

In Mr Read’s opinion there was a strong basis to infer Mr Winfield left the girls with a stranger “so he could dispose of Bronwyn’s body in Sydney”.

If Mr Winfield had instead taken the girls to stay with relatives that morning, they would undoubtedly have raised questions about Bronwyn’s whereabouts and may have tried to access the boot of his car, for instance to assist with luggage.

“This is what actually occurred when Jon arrived at my home on the afternoon of 17 May, 1993,” Mr Read told the coroner.

Tests conducted by podcast listeners on cars matching the Winfield family’s 1987 Ford Falcon XF sedan showed Bronwyn’s body would have comfortably fit in the boot.

The boot was “incredibly clean” and had no vinyl lining when Mr Read saw it on May 17, with Mr Winfield packing very limited clothing for the girls in pillowcases despite the approaching winter.

The letter to Ms O’Sullivan states that new information suggests the previously unexamined Illawong site “might be of crucial relevance”.

In May 1993, it was a vacant block of land owned by Sutherland Shire builder Glenn Webster in a new housing estate, and was being readied for construction of a two-storey brick home.

Mr Webster asked Mr Winfield to help build the home.

Sutherland Shire Council documents obtained by Mr Read show a garage slab inspection was conducted on Thursday, May 13, 1993, three days before Bronwyn disappeared.

It was understood to be a pre-concrete pour inspection.

Prior to the council documents being obtained, The Australian’s national chief correspondent Hedley Thomas obtained information about a concrete pour from a confidential source.

The informant said he saw Mr Winfield on the afternoon of May 17, 1993, and questioned him about his unusual movements.

“They asked Jon where Bronwyn was and why he had rushed down from Lennox Head overnight with the girls,” the letter states.

“Jon became angry and ‘blurted out and snapped’ that he had to be back in Sydney for ‘a concrete pour in Sutherland (Shire)’.

“They considered Jon’s behaviour, level of agitation and anger over these matters unusual. They considered Jon appeared to regret having disclosed the concrete pour to them. They had been suspicious of the concrete pour for some time in connection with Bronwyn’s disappearance. They are prepared to put this information into a statement to police.”

It could be inferred Mr Winfield was referring to an imminent concrete pour at the Illawong property, the letter states.

Mr Webster, a respected builder who is not accused or suspected of any wrongdoing, told Thomas he had come to suspect Bronwyn’s body could have been concealed beneath concrete at the property.

Police had not asked Mr Webster about this possibility, last speaking to him more than 20 years ago.

A 2002 inquest did consider the possibility Mr Winfield buried Bronwyn under concrete at a building site, but the focus was on a property at Newrybar near Lennox Head.

“The Illawong property does not appear to have been considered,” the letter states.

Former detective Glenn Taylor began investigating Bronwyn’s disappearance in 1998 and provided the inspiration for Mr Read’s letter to the coroner.

During interviews for behind-the-scenes videos for the podcast in late 2024, he said if he was in charge today, he would “be putting in a written request to the coroner seeking a coroner’s order that the site be examined”.

He added: “I think that is the way to move forward now – to try to eliminate the possibility that Bronwyn is, in fact, under that slab.”

Mr Read wrote: “I consider the other potentially incriminating evidence could possibly include clothing (both Bronwyn’s and Jon’s), bedsheets, the car boot liner and Bronwyn’s handbag.”

Then deputy state coroner Carl Milovanovich in 2002 terminated an inquest and recommended a known person, Mr Winfield, be charged over Bronwyn’s murder.

Then director of public prosecutions Nicholas Cowdery refused, citing insufficient evidence.

“I note, however, that Mr Cowdery reached the same view in relation to the murder of Lynette Dawson (nee Simms) and Chris Dawson was prosecuted by a subsequent DPP and convicted of murder,” Mr Read’s letter states.

Mr Read sent the letter to Ms O’Sullivan on December 5, 2024, and is still awaiting a reply.

Do you know more about this case? Contact Hedley Thomas at thomash@theaustralian.com.au