Nowhere Child podcast: walls are changing, but William Tyrrell’s memory won’t fade

Australia is a nation haunted by tales of missing children. None are as surreal as this | PODCAST

The front door opens: “Sorry everything’s so shit.” That’s William Tyrrell’s grandmother speaking. She’s laughing as she says it, because what she means is, her son, who is William’s father, has been painting the house.

It had been a faded yellow. But now it’s turning bright white, and that has made her happy, although it’s not really to do with the paint.

“Do you think it means he’s getting better?” she whispers.

William’s father — by court order, he can’t be named — is living the hardest decade imaginable. Some of his punishments he saw coming and some he’d say he deserved, but the loss of a child?

“You wouldn’t wish it on your worst enemy,” said one senior detective, who worked on the Tyrrell case, in which a three-year-old just like that — snap! — disappears. “The things that go through your mind, thinking: is he alive? And if he is …” He trails off.

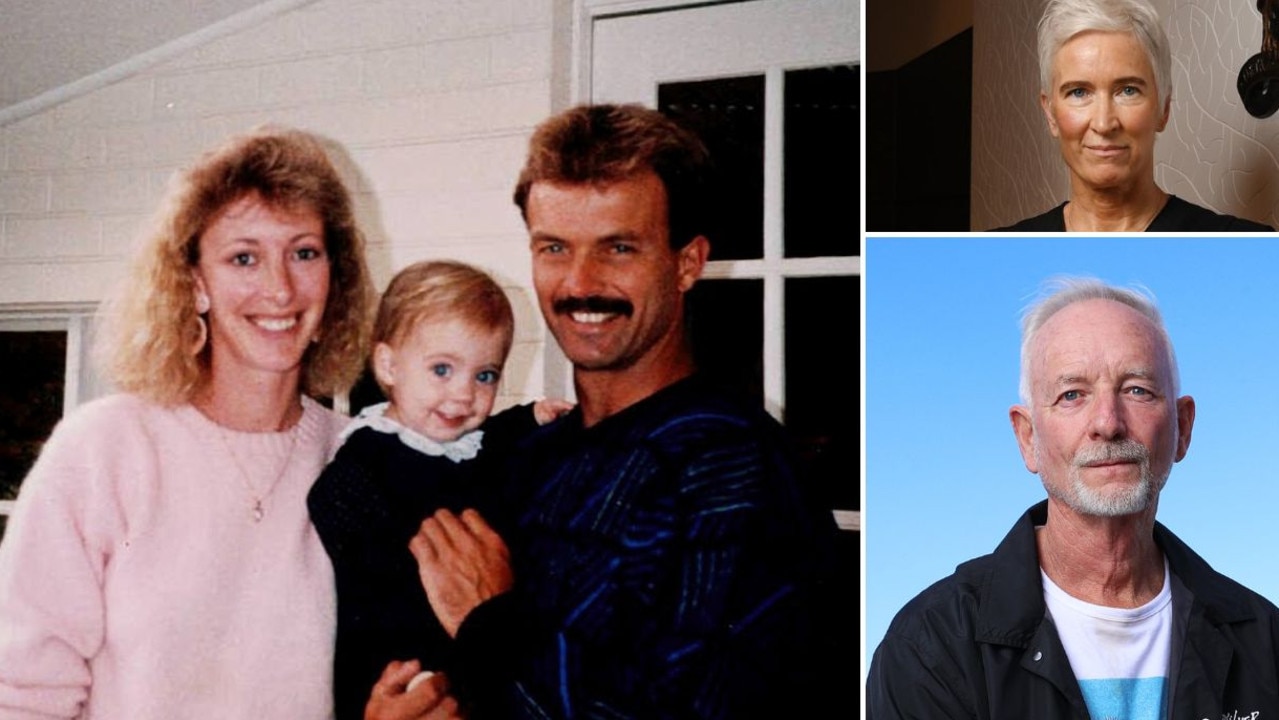

William’s story starts 10 years ago, when his father met a girl. In 2010, they had a daughter. Three months later, that child — a girl called Lindsay in court documents — was taken into state care. What was the issue?

Violence. It wasn’t directed at the child. Lindsay’s mother went to a party. It got out of hand. Police got called. She spat at police. She was aggressive. She has mental health problems, and is addicted to drugs. She lashed out, in a way that made officers feel unsafe.

They decided Lindsay was “at risk of harm” — that’s a formal categorisation — and handed her to the NSW Department of Family and Community Services, whose welfare officers put her into foster care, along with 47,000 other Australian kids.

Yes, 47,000 — a number the size of a regional town. The mother got pregnant again, this time with William. He was born on June 26, 2011, and when he was nine months old the department came for him too.

The couple had told police they were fighting all the time and taking drugs. FACS told them they shouldn’t live together. The relationship was too volatile. If they kept up with the romance — and truly, they were like magnets, unable to stop screaming at each other, and being together — they were at risk of losing their son.

They stayed together. They lost their son.

William’s father didn’t give up so easily this time. He took off with him, hiding out in a granny flat for close to seven weeks. It was a crazy thing to do, and he explains his reasoning like it’s the most obvious thing in the world: “I didn’t want them to take William. He was my son.”

Police tracked the family down. William’s father was arrested, and William went into foster care.

Now the story turns surreal.

Foster care can be a bit hit-and-miss, with some homes truly worse than the homes from which the children have been removed.

William’s placement wasn’t like that: he went to a home in one of Sydney’s finer suburbs, with a swimming pool, and plantation shutters, and polished boards, and big-screen TVs. William’s sister, Lindsay, who had been staying elsewhere, soon joined him — the department has a policy of keeping siblings together where possible.

Then one day … gone.

That’s how the foster parents have described events: William was there one minute, playing outside a house in Kendall on the mid-north coast of NSW, and he was gone the next, and they say it’s torn their hearts out.

Experts from around the globe have been left perplexed by the case. One senior police officer who worked on the investigation — none can be named — told The Weekend Australian: “It’s like The X-Files. Like he vanished. Literally vanished.”

Five years on, the crime still haunts former NSW premier Mike Baird, who authorised a $1 million reward — the largest for a missing child — for information that might lead police to William.

“I remember getting the advice on that, and I thought if that’s the thing that makes somebody come forward, let’s do it,” he told The Weekend Australian. “You can only imagine as a parent … you can’t imagine, actually …”

He trails off.

Former NSW police minister Troy Grant, who has since retired, authorised resources of the type never before seen in a missing person case. There were at one point 26 homicide detectives working on the Tyrrell matter. Six hundred names made it onto the list of persons of interest.

There have been 3000 calls to Crime Stoppers from members of the public and more than 1000 possible sightings of William. Each of those calls was logged and followed up.

Detectives have been asked to handle 11,000 pieces of information. There have been mistakes and miscalculations and allegations of misconduct, but many have worked, and searched, harder and more thoroughly than ever before in their lives.

And yet we still don’t know what happened.

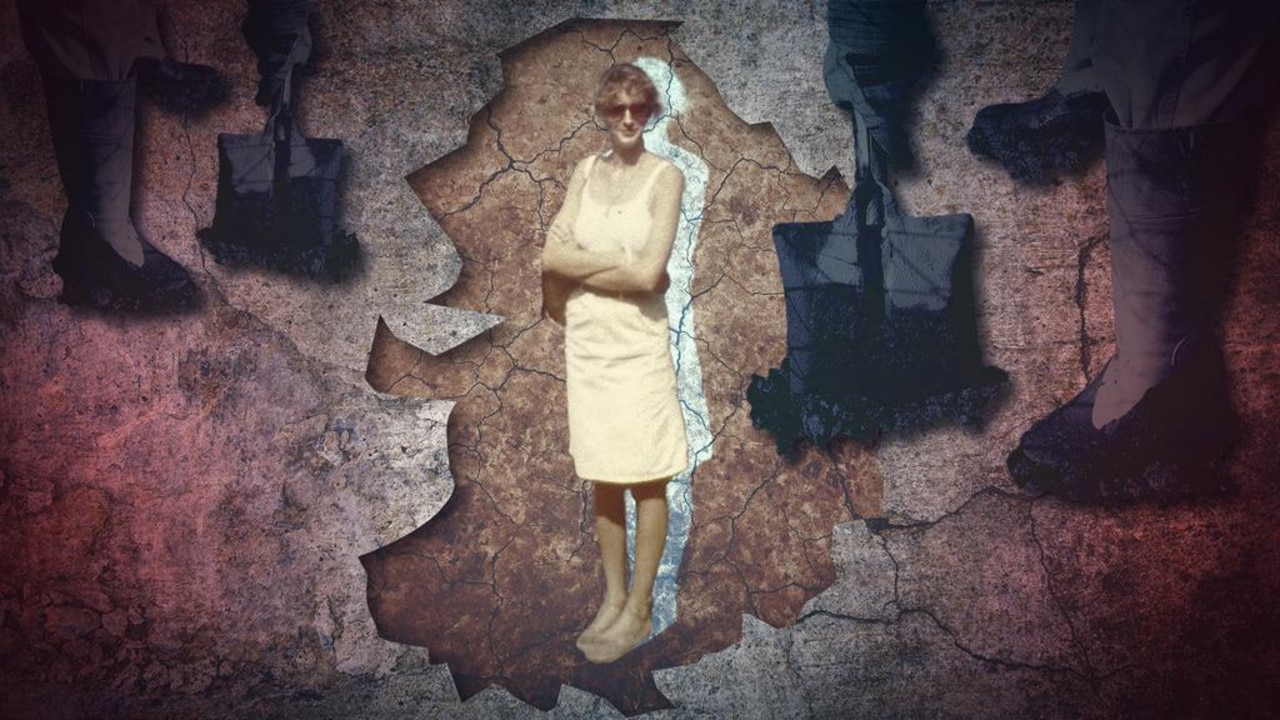

Australia is a nation haunted by tales of missing children. William’s case is different from the others. Here is a little boy taken by the state for his own protection, who goes missing and no one can say what happened to him.

William’s foster parents have said they were visiting his “Nana” — his foster mother’s mother — in Kendall, a sleepy village of no more than 1100 people. He got up in the morning and had some help putting on his favourite Spider-Man suit. It was a two-piece costume, and he had a Spider-Man T-shirt on underneath. He was, in his foster mum’s words, “Spider-Manned out”.

He had breakfast. He drew some pictures. He ran around the garden for a while, playing “mummy monsters” — a game in which his foster mother would chase him, and he’d chase her. They had a bit of a go at climbing a tree. She put him in, and he objected, saying: “No, Mummy, too high.” Because he had started calling her Mummy. He was confused by his circumstances. He was three, and it made sense to him that the people who tucked him in every night were his parents.

The Fosters — that is not their real name, which is protected by court order — had made an inquiry about adopting him, which would have made them so.

And then he was gone.

The Fosters have repeatedly and strenuously denied any involvement in William’s disappearance. They have given a number of interviews over the years, in which they’ve explained how much they loved him. They have co-operated with every aspect of the police inquiry, surrendering phones, computers and cars for forensic analysis.

William’s biological parents have also co-operated with every aspect of the inquiry, although they feel that many details have been kept from them.

William’s father is not an easy man to talk to because he’s of so few words. He acknowledges he wasn’t doing enough, back in 2013, to satisfy the courts that he was capable of taking care of William.

He still had hope of getting him back, however, because he’d had another child, and that child had been allowed to stay in his care, plus they had a fourth on the way. He was out the back of their family home, smoking a cigarette, when police knocked on the door on September 12, 2014. They told him: “William’s missing.”

“He’s f..king what?” he replied.

He can barely think about it now, saying: ‘They’re playing together and you know it could have been the other way around, they could have taken (Lindsay) and not William, or like both could be missing.”

Does he think he’ll ever find out what happened?

He pauses for an age.

“I’m afraid,” he says, finally.

William’s father’s life fell apart after William went missing. He has been to prison several times, mainly for stealing. He has lost his driver’s licence. He recently had a go at getting it back but failed, and is now saving for the $58 he needs to take the test again. His relationship with his girlfriend ended, and the two youngest children were removed from her care last year.

But then William’s father was informed, just a few months ago, that the NSW Coroner had decided to hold a formal inquest into William’s disappearance.

He got himself together, and attended every day, without a lawyer, because he could not afford one. His plight attracted the attention of an independent children’s advocate, who wrote to Legal Aid requesting assistance.

“I am the father of four beautiful children, one of whom is missing boy William Tyrrell,” he said, in the letter she drafted.

“I make no excuses for my past behaviour. I may not have had William and my daughter in my care for long but I love my children.”

He explained how he’d been found in an “incoherent state” after shoplifting “miscellaneous items” such as children’s toys and been sent to prison; how he’d been asked to submit to regular drug testing “to prove that I was clean and free, which I am proud to say I passed”.

“He is my son regardless of his status as a foster child, and I am still his father, regardless of my personal circumstances,” he said.

His application for Legal Aid was approved last week. He cannot predict the outcome of the inquest — nobody can — but, he said: “Whatever fate or the future may bring, (this) has had an enormous impact on me as a person in general. I try every day to work at overcoming something so traumatic. But poor William. He has suffered the most.”

Nowhere Child: Missing William Tyrrell, the first episode of The Australian’s new podcast series about a three-year-old child who vanished while in state care, is out now. Search on your podcast app for Nowhere Child.