'IN a way, I see the ABC arts slate as a kind of year-round festival and what I'm trying to do in the programming, commissions and in the acquisitions I make is to try and get a balance across art forms, across tone, across a kind of geography and across demographics."

This is Katrina Sedgwick talking, Aunty's head of arts, who's been in the job a little more than a year. And she's certainly continued the changes and rejuvenation brought about by her predecessor Amanda Duthie, as well as authoritatively making the position her own. (Interestingly, they actually exchanged jobs, Duthie taking over Sedgwick's curatorial role as director of the Adelaide Film Festival.)

Sedgwick has extended the functions of the ABC's famous but rarely read charter. Aunty is now firmly committed to the full depth and breadth of arts practice and activities in Australia, including in the digital sphere, with the terrific ABC arts online, which really has become another channel. It's a space where the best of ABC arts content text, audio and video is curated, as well as creating its own content, and it engages innovatively with the particularities of place and region.

The ABC no longer simply reflects and promotes the Australian performing arts, as its charter suggests; it's also in the business of creating art across the genres - art that has many broadcasting lives built into it.

A radical spirit of co-operation was begun under Duthie and continues under Sedgwick's canny stewardship.

And the ABC has become an effective partner of all sorts of arts organisations, some of which don't have the infrastructure, intellectual property, knowledge or the archives of the national broadcaster. It's a new way to serve the public interest - the ABC is creating a stake in its own output, part of a broader ecology made up of small producers.

I've been taken this year with Sunday Arts Up Late, presented by the energetic playwright and director Wesley Enoch, which began last summer and quietly sneaked up on us. Enoch presents high-end, cutting-edge arts content from Australia and around the world, including feature-length documentaries, biographies, short-run series and one-off events. And this week there are two quite special new local documentary features, On Borrowed Time, David Bradbury's study of filmmaker Paul Cox, narrated by David Wenham, and William Yang: My Generation, directed by Martin Cox with Bridget Ikin as executive producer, both of which would never have been shot without the ABC's commissioning clout.

The two movies are oddly like obituaries, nostalgic and respectful and, like the best obits, certainly not without their moments of humour, even though both subjects happily are still with us. On Borrowed Time is Bradbury's tribute to the prolific Melbourne filmmaker and the way he faced the challenge of battling cancer in 2010. It's a fine, compelling movie, suitably elegiac and full of arresting and sometimes startling imagery.

Bradbury is one of the great film journalists whose other features include Frontline, a portrait of war cameraman Neil Davis, and Chile: Hasta Cuando?, his portrait of the brutal Pinochet military dictatorship. But On Borrowed Time is less polemical, more esoteric. Bradbury calls it "a journey in the mind which requires, like watching a Paul Cox film, a certain interest in the big questions of life".

Needing a liver transplant, his blood group rare and shared by only a tiny group of Australians, Cox, raised in The Netherlands, had just six months to live if a donor were not found. Bradbury's camera is with him for much of this time, capturing both the idiosyncratic charmer and the rousing cantankerous and curmudgeonly artist. Cox is a divided soul, but he's been an enduring, often cranky, part of an industry that began its resurgence in the early 1970s.

Bradbury covers Cox musing alone in his Melbourne apartment, working on a memoir by hand, as he waits for a potential donor to die. The film starts with time passing: images of the many clocks Cox surrounded himself with through the years. None kept the same time. "In his private world, which is far from ordinary, he lets the clocks have their own life," Wenham tells us. "In recent years, one by one, the clocks have wound down and his Albert Park sanctuary is slowly falling silent."

Less poetically, Bradbury also tracks his subject's visits to hospital for treatment across several months, Cox full of loathing for the banal radio music that plays incessantly. He is not the easiest of people.

As critic David Stratton says, Cox pursues themes as a filmmaker that are important to him and assumes they should be important to everyone else, obsessed with love, beauty and death. (Stratton also relates the blistering retort he got after filing a negative review of Cox's movie, Salvation.) Bob Ellis, who wrote several movies with Cox, good-naturedly calls the director "a persuasive prophet stroke charlatan". Long-term friend Phillip Adams notes Cox is "a man who prefers disciples to collaborators".

These remarks, and those of others too, are honest and direct, all delivered with a slight smile, but Cox is tough on himself at times as well, wearily lachrymose he suggests he has spent so much time looking for the skull behind the face that his work has worn him out.

There are many quite beautiful images from his movies that Bradbury uses elegantly to illustrate and comment on Cox's poetic musings, including from Man of Flowers (1983), My First Wife (1984), Exile (1994) and Human Touch (2004). And other interviews include friends - the actors Wendy Hughes, Julia Blake, Chris Hayward, Wenham and long-time muse Gosia Dobrowolska.

As Cox did himself in his film The Remarkable Mr Kaye (2011), which followed the fading away of his friend Norman Kaye as the impenetrable curtains of Alzheimer's disease folded around the brilliant actor, this film also seems to pose the unanswered question: is there, finally, any point to placing one's existence at the service of cinema?

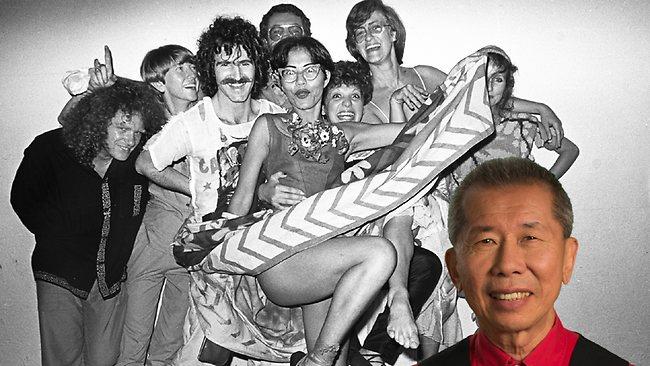

William Yang: My Generation is the story of how a young actor and writer found a role as a documentary photographer of the emerging artistic, literary, theatrical and queer circles of Sydney in the 1970s and 80s.

And how he then became better known for his revealing live shows in which, standing beside his sometimes starkly beautiful photographs, he told their stories.

They are poignant fly-on-the-wall narratives about Sydney's eerie charm circle of decadent painters, writers, actresses, hangers on and street people, first-hand accounts of thrills born of the salacious and vicarious.

Brett Whiteley grows more and more demonic as the years and the smack age him badly. The statuesque Kate Fitzpatrick gives the impression the world revolved around her pneumatic form as, stage and film darling, she was rolled out at celebrity dinner parties and photo opportunities as a blonde wit, wearing tight-fitting dresses cut high on the thigh and low on the neck.

Patrick White emerges as a runcible-faced clownish figure, his head growing longer and longer as the years move on, a nice chap who looks as if he would have been great company on a good night.

And designer Jenny Kee seems to have been at many of them, while still appearing to have clothed the entire city in flowing coloured fabrics, an irresistible force of fashion.

The film at times seems to document a boisterous carnival, something compelling and oddly buoyant. Like Whiteley, many of Yang's subjects appear to have shared William Blake's belief that "the road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom". But there is terrible sadness too as the AIDS crisis reaches the party and drug culture and the bohemian social scene.

Unlike so many people he photographed, Yang suggests, over a shot of a needle, he has never been one to open himself to too much humiliation or to take obsessive risks. This may even have saved his life when so many of his peers died of AIDS. "We were the high generation," he says. "We experienced existence at a heightened level."

He says his camera protected him while others pushed themselves to the limit; he became the observer, the voyeur.

"I wonder if he ever knows what he captures in those images and maybe that's what's so magical about them," Sedgwick says. There's the sense through them of a life lived on the run, experiences flipping past one after another, with all those famous people making art on the fly.

And Yang gives you the sense of not quite knowing who he was until many of the people he photographed had died, and he had become a performer standing on stage alongside their images. "I've spent quite a lot of time on my photos, devoted my life to them, you might say," he tells us at the end of his film, sitting at a small table surrounded by yellowing folders of them, trying to make sense of the past. "They require a lot of attention, they're like children and, like the children I never had, they will tell my stories when I'm gone."

Yang is so veiled and gives so little away you do find yourself wanting to say aloud, "Yes, William but what do you really think?" I'm sure he would just give that slight smile on his largely immobile countenance, lift an eyebrow fractionally and move on to the next photograph. He is a beautifully controlled performer, a delight to watch, every line he delivers in that oddly hesitant voice full of subtext.

Out of the raw material of himself, he has created a narrator whose existence is integral to the tale being told. This is the hardest thing to do in the still fashionable literary genre of memoir, which Yang has so carefully adapted to theatre presentation.

His shows are not simply a transcription of the stories he has possibly recounted many times but a crafted narrative in which he has imagined himself in relation to the various subjects he photographed.

As Yang says at the start of his film, he saw himself initially as someone who did "monologues with slide projector". His publicists disdained this job description, preferring "multimedia artist"; now he is happiest with "storyteller". And he tells them well, with wry, understated style, if a little uncritically. As VS Pritchett once said of the memoir genre: "It's all in the art. You get no credit for living." Neither film should be missed.

ABOUT as far removed from art as TV can get is VICE, from HBO, which starts this week on Foxtel's Fox8. It's a new magazine series from the similarly named magazine company noted for its brazenness and a bare-bones approach to journalism. The HBO show, a spin-off from a successful magazine and online empire, received a great deal of press for the filming of the first episode depicting Dennis Rodman's recent controversial trip to North Korea. Not available for preview, it goes to air locally a few days after its US broadcast. The NBA Hall of Famer was part of the delegation including VICE correspondent Ryan Duffy and three players from the Harlem Globetrotters who spent a week in basketball-crazed city Pyongyang. While there the "basketball diplomats" met North Korean leader Kim Jong-un before taking on that country's "dream team". A week later, of course, North Korea scrapped its 1953 armistice with South Korea and threatened a pre-emptive attack on the US.

"Essentially, the show will be what we do best: a variety of mind-melting stories from around the globe and immersive detours into the scariest, most absurd, and flat-out unbelievable cultures and situations," the series website says. "Here are a few ideas we're spitballing right now: a portrait of child Taliban suicide bombers, visiting underground voodoo heroin clinics in New York, riding along with Somalian pirates, and booking a teeth cleaning with a Satanic dentist in the Pacific Northwest."

You get the idea, but VICE first rose above lad-magazine status with Heavy Metal in Baghdad, the critically acclaimed 2007 documentary about an Iraqi metal band trying to make it in a war zone. And subsequently its online news and travel stories - many of which can be seen on the VICE YouTube channel, which has more than a million subscribers - have been praised for their spare and fearless approach to journalism.

Founded in Canada by Shane Smith and Suroosh Alvi in 1994, what started as a free magazine called Voice of Montreal, with a proudly boorish reputation for provocation and an aggressive hedonism, has matured in recent years. VICE Media is now a leading global youth media company with bureaus in more than 30 countries including Australia, its ambition, according to Smith, to become a kind of MTV on steroids; it's also been described as the love child of National Geographic and the late great gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson.

Smith, who calls himself "the poor man's Hemingway" and who often appears on screen, is one of TV's great new characters. "Bon vivant, storyteller, drunk", is the way he summarises his lifestyle. "Let's have 14 bottles of wine at dinner, roast suckling pig and a story about chopping a dude's head off in the desert."

The HBO series showcases Smith's brand of participatory storytelling - which he calls "immersionism", his reporters embedded in dangerous far-flung places, their pieces aimed at a core audience of males between 18 and 34.

And by the looks of it, Smith has arrived at just the right time to create the world's next big network, accessible to the internet-saturated minds of young people.

Sunday Arts Up Late: On Borrowed Time, Sunday, 9.30pm, ABC1

William Yang: My Generation, Sunday, 10.30pm, ABC1

VICE, Wednesday, 9.30pm, Fox8