Widow’s might

This mystery thriller is a magic show, complete with smoke and mirrors.

The Widow is from Jack and Harry Williams who once wrote sitcoms, separately, before they decided to join forces and give scripted drama a try. The result was The Missing, a compelling thriller that propelled them to the top tier of British writing talent. They successfully followed up that series with One of Us, a dense psychological crime mystery, dubbed “family noir” by British critics, a second season of The Missing, reverse-narrative crime drama Rellik, and that emotional thriller Liar.

With The Widow they deliver highly watchable, if occasionally deliberately perplexing, old-fashioned entertainment — a mystery thriller that’s well acted, and vigorously directed with some cinematic skill without being mannered and drawing attention to itself. And, like so much of their drama, it’s about the way tragic events have lingering effects on the central characters, the post traumatic effects of loss.

Kate Beckinsale, yet another famous film actress choosing to star in a television show, is Georgia Wells, a once-happily married woman now living as a recluse in a small wooden cottage in the Welsh hills, still mourning the death of her aid-worker husband who died in an African air crash three years earlier.

While everyone close to her has told her that he perished, Georgia believes he’s alive since they never found his body and there’s some evidence of one lone survivor. After falling while out walking one morning she attends the village medical clinic where she believes she catches sight of him after she glimpses news footage of a riot in Kinshasa.

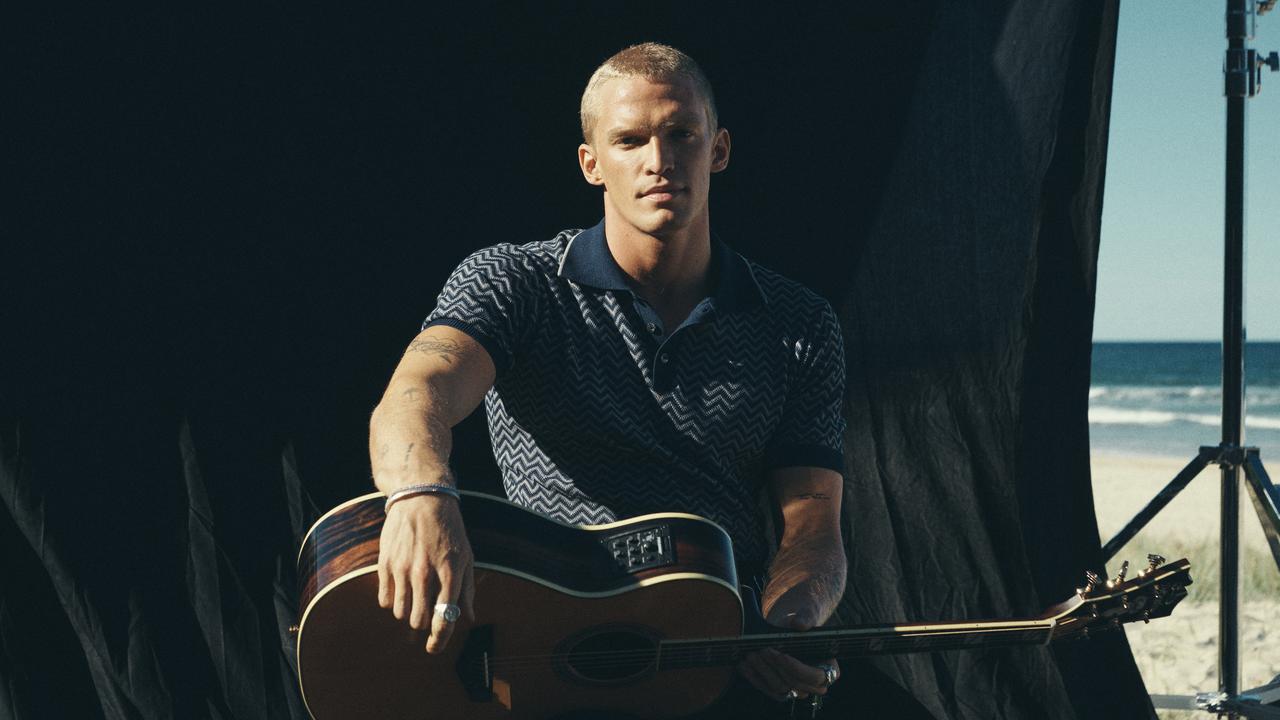

Is the man she sees in the orange cap really Will Mason (played in the series by an impressive Matthew Le Nevez, the young Australian actor last seen here as motor racing legend Peter Brock in the Channel 10 miniseries)?

As they often do, the Williams brothers play with time and chronology from the beginning and the plotting ricochets between Georgia’s and Will’s past and the circumstances of the chaotic present as, against all advice, she begins what seems like a hopeless search for answers in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Multiple storylines intersect and intertwine with Georgia’s, which may or may not be directly related to the fate of Will Wells. A young girl, serving as a reluctant child soldier, continually attempts to preserve the life of a younger child, an assault rifle never leaving his hands; a blind man from Iceland, hoping to be chosen for miraculous eye surgery, may be a survivor and begins a romance in Rotterdam with a blind piano tuner; and there’s her friend Emmanuel, a man who lost his wife on the same ill-fated flight, who acts as her local contact when she reaches the Congo.

And just who is the man they call Mr Tequila, a South African who at the time appeared to have lost someone when the plane went down but who now seems to be involved with militia forces?

The Williams boys always give the impression in interviews that writing for them is like a kind of magic show. Not that they ever say much, just joke about a lot, maybe still comedy writers at heart, though they appear to have developed a bit of an obsession with the TV thriller. They love smoke and mirrors, giving the impression they are some kind of idiots savants in possession of a magic formula for writing, which they will not reveal lightly. They have an enviable gift for the mystery story, the investigation and discovery of hidden secrets with bad consequences, the gradual isolation of clues and the attempt to place them in their rational place in a complete scheme of cause and effect. Few writers going around have this gift for this narrative of mystery even if at times you feel your head bursting from trying to follow the complex trail to the final resolution.

Ricky Gervais’s new original six-part Netflix series, After Life, is a comedy that finds humour in grief, mortality, and even euthanasia, its tagline: “Misery loathes company”.

Written, directed and executive-produced by Gervais, he plays Tony in the six-part series, a reporter for the local newspaper, The Tambury Gazette, who has decided that life without his wife, Lisa (a brilliant, effervescent Kerry Godliman), who recently died of cancer, is devoid of meaning.

The only thing that could make him happy, he says, is Lisa being around and that can’t happen any more so there’s really no point in being thoughtful and caring and having integrity any more. “If I become an arsehole and I do and say what the f..k I want for as long as I want, and then when it all gets too much I can always kill myself; it’s like a superpower,” Tony tells his kind but naive brother-in-law Matt, played with a lovely long-suffering edge by Tom Basdale. Tony morosely spends a lot of time watching clips of Lisa on his laptop — recorded it seems on her deathbed — who constantly reminds him how to live: how to turn off the alarm as he leaves the house, to feed the dog and to put the rubbish cans out each Tuesday. But for the rest of the time, cantankerous and grumpy, he seeks confrontations with almost everyone he encounters. “A good day is when I don’t go around wanting to shoot every stranger in the face and then turn the gun on myself,” he tells his rather ineffectual therapist.

But there’s still the dog to take care of and each day he somehow makes his way to the newspaper office, despite his disdain for his colleagues — “It should be everyone’s moral duty to kill themselves,” he tells a newcomer — and his aversion to the subject of the feature stories he writes about the local community, like the widower who has just received the same birthday card from five people.

It all sounds rather depressing, miserable viewing but it may be one of the best things this interesting comic has done. Gervais, as he often does, reminds one of English comedian Tony Hancock with his air of saggy melancholy, the mood of aimless tedium, and his belief that great comedy can arise from frustration, misery, boredom and insomnia. And like Hancock, Gervais is always the little fat man trying to keep pace with an increasingly formidable world, yet fated to remain an outsider forever.

There’s a certain comedy here of recognition, our own pathetic thoughts of rebellion against the petty curses of everyday living articulated, centred on Gervais’s scent for the cliche of our existence, however slight and trivial they seem. Like running out of dog food, forgetting to wash the dishes, the way people chew potato chips too loudly, or anger at a lazy postman, or a busybody reminding us to put the dog on the leash in the local park.

After Life is not all that laugh-out-loud funny — though there are some very funny moments — but convincing and totally believable as a man in the depths of grief. It’s another of Gervais’s wonderfully confronting characters, a man who can’t stop revealing what’s in his resentful head, doing what no one else would, being unlikeable and rudely perceptive.

Gervais knows where the boundaries are, what decent sympathies he may be trampling to death, and why sadness may be a condition of life that can’t be obliterated even by laughter.

The Widow is streaming on Amazon Prime Video. After Life is streaming on Netflix.

Readers seeking support and information about suicide prevention can contact Lifeline on 13 11 14.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout