Phantom Atlas by Edward Brook-Hitching: imaginary islands

The Phantom Atlas shows how places that are not there can endure, sometimes for centuries, on maps.

In November 2012 the world lost an island. For more than 100 years Sandy Island had appeared on maps in the Coral Sea east of Australia and west of New Caledonia. However, when a team of marine scientists reached the location they found nothing but open water.

The documented island appears to have owed its phantasmal existence to the way modern digital maps draw on satellite data and old British Admiralty maps. In 1774 James Cook sighted a “Sandy Island” about 400km farther east from Sandy Island’s modern position. In 1876 a whaling ship located an island closer to the modern co-ordinates and sandy islets were recorded in an 1895 British Admiralty chart and a later Australian maritime directory.

From 1979, however, French hydrographical charts started removing this non-existent isle. But even after the 2012 voyage it was not entirely expunged from our maps. Type “Sandy Island” into Google Maps and its former “location” is pinned in the vastness of the South Pacific, but with an explanatory note that it is “a non-existent island that was charted for over a century”. Non-existent, but still on the map.

The Phantom Atlas, an intriguing book by self-confessed “incurable cartophile” Edward Brooke-Hitching, shows how places that are not there can endure, sometimes for centuries, once a map-maker has inked them in. “This is an atlas of the world,’’ he writes, “not as it ever existed, but as it was thought to be.’’

Often people desperately wish such places were real. In 1997, as the US and Mexico were preparing to divide up pockets of international waters in the oil-rich Gulf of Mexico, Mexico sent a navy vessel in search of the island of Bermeja, which had been placed off the Yucatan peninsula on charts from the 16th to the 19th centuries. Nothing was found. Conspiracy theories spread that it had been destroyed by the CIA, using no less than a hydrogen bomb.

It is not just in remote parts of the great oceans that mapped locations can have long, elusive lives. A note of “Ruins” on a map by Victorian explorer William Leonard Hunt, who led an expedition into the Kalahari desert, triggered numerous attempts to locate the “lost city of the Kalahari”. The most recent, which employed microlights to search from the air in 2010, is unlikely to be the last.

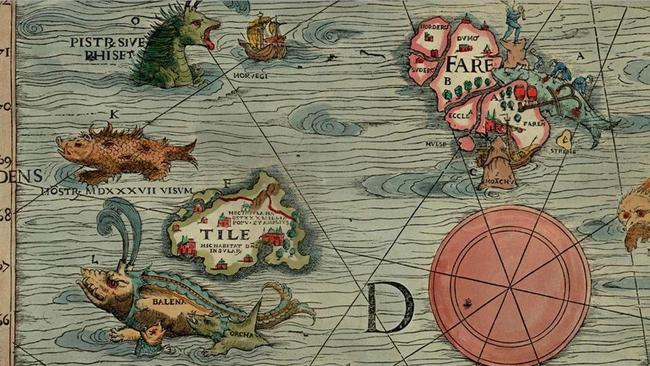

Sometimes maps are wrong because they are based on myth. Thule, the unknown land believed to lie in the frozen north, appeared in the writings of the ancient Greeks and then Virgil and Pliny. In the 16th-century Carta Marina, made by the Swede Olaus Magnus, Thule was located northwest of the Orkney Islands off Scotland, surrounded by sea monsters.

Many maps are inaccurate because of genuine mistakes, caused by inadequate measuring systems or by misinterpretation of a mirage or low cloud formations. Then there are maps that are fiction because the cartographer was a liar. Perhaps the most shameless charlatan in this book is Gregor MacGregor, a soldier of fortune and great-great-nephew of Rob Roy, who arrived in London in 1822 claiming the king of the Mosquito Coast had granted him his own kingdom in what is now Honduras: the territory of Poyais.

Poyais, MacGregor said, was a land of fertile soil and abundant gold, and all he needed were investors to exploit it. He conned a fortune out of investors. Two ships of colonists sailed to Honduras, where they not only found Poyais did not exist, but were stuck in a malarial swamp.

A chart of the Arctic from 1913 features Bradley Land and Crocker Land. Neither exists, but they attest to the fierce rivalry between the American explorers Frederick Cook and Robert Peary as they competed to be the first to reach the North Pole.

While this book is mainly about places that never were, there are also tantalising suggestions that even in the satellite age there are still places that appear on no map, but should do. After Sandy Island was officially erased in 2012, Society of Cartographers president Danny Dorling said it could still be out there: “It’s unlikely someone made this island up. It’s more likely that they found one and put it in the wrong location. I wouldn’t be surprised if the island does actually exist somewhere nearby.”

Damian Whitworth is a feature writer at The Times.

THE TIMES

The Phantom Atlas: The Greatest Myths, Lies and Blunders on Maps

By Edward Brooke-Hitching

Simon & Schuster, 256pp, $49.99 (HB)