Obituary: composer Peter Maxwell Davies, master of Queen’s music

On his trips to Australia, Peter Maxwell Davies developed ties with local composers and drew on indigenous music.

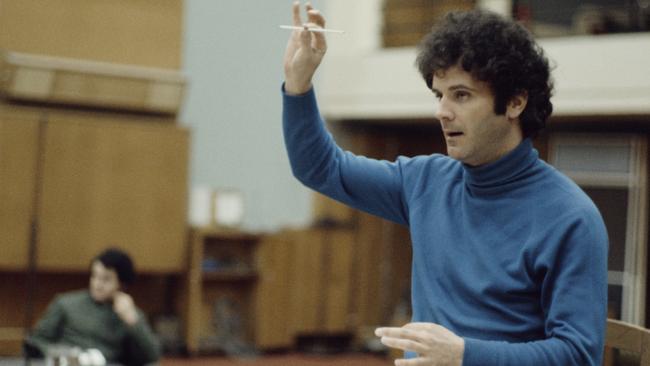

An avant-garde firebrand who once provoked an audience walkout at the Proms; a prolific and protean craftsman who wrote reams of music for every medium; a republican and socialist who became master of the Queen’s music and then proceeded to castigate the “philistines” at the heart of the British establishment — Peter Maxwell Davies was arguably the most influential British composer since Benjamin Britten.

And Max — as he was known — had a life as flamboyant as anything in his music. Though he spent the final 44 years of his life on the remote islands of Orkney, his opinions and his mishaps — which included being prosecuted for eating a dead swan, and being swindled out of hundreds of thousands of pounds by his own manager — regularly made headlines in the British press. A born provocateur, he mellowed with age but never lost his talent or his relish for making mischief and scandalising the prudish and conservative.

He also made multiple trips to Australia, becoming close to Richard Meale and other local composers and drawing on Australian sounds, especially indigenous, in his own work. In 1965 he was composer in residence at the Elder Conservatorium of Music, later returning to South Australia as guest artist in residence of the Barossa Music Festival in 2000.

At the time, he told The Advertiser: “I don’t like the feeling when I’m not going all the time. After all, you keep learning until you kick the bucket.’’

His chamber opera The Lighthouse is a terrifying study of the psychoses caused by childhood abuse, repressed sexuality, religious fanaticism and establishment cover-up. Much more recently, the opera Kommilitonen!, written for music students in New York and London, is a moving and powerful celebration of youth protest throughout the 20th century.

The savagely discordant music-theatre pieces he produced in the late 1960s were incomprehensible to many British music critics. His 1972 grand opera, Taverner, proved far too complex, musically and philosophically, for even those performing it at the Royal Opera House to fathom.

Later, when he tamed his musical style and concentrated on writing in conventional forms for conventional forces, the criticism went the other way: he had “lost his boldness”, he was writing too much, and his music had become dull and functional. That view was exacerbated during the 10 years from 2004 to 2014 when he was master of the Queen’s music. Maxwell Davies claimed he was merely tailoring his music to suit his patron. “The Queen doesn’t like dissonant music,” he said.

In any case, he was adept at transforming his style to suit his intended audience — royal or otherwise. Having made his name with acidly atonal music, he went on to write pieces so tonal and tuneful that they almost qualified as easy listening.

Peter Maxwell Davies was born to working-class parents in Salford in 1934, and taken to see The Gondoliers by Gilbert and Sullivan before he was five. The experience opened a window for him, not so much in musical terms but as a glimpse of a potential life not bound by his grandfather’s shop or the factory where his father worked.

Between 1952 and 1957 he was a student, first at the University of Manchester, then at the Royal Manchester College of Music. He became friendly with composers Harrison Birtwistle and Alexander Goehr, the pianist John Ogdon and the trumpeter and conductor Elgar Howarth. The others thought Maxwell Davies’s interest in medieval and Renaissance music was retrogressive, but he had already discovered Bartok, Schoenberg and Stravinsky, and at university he had access to the revolutionary scores of Boulez and Stockhausen.

After studying in Rome, his life took a new direction. He became the music teacher at Cirencester Grammar School. The need for a regular income prompted this unexpected move, but it had a beneficial impact on his compositional style, too. To write music his pupils could manage, he had to simplify his style considerably.

Three years later, a Harkness fellowship took him to America to study with Roger Sessions at Princeton University. Here, he had time to think — in particular about the opera Taverner, which had been gestating since 1956. Returning to London in 1965, he reunited with Birtwistle, and the two decided to start a flexible music theatre of avant-garde specialists.

Worldes Blis, a massive orchestral “motet”, prompted the noisy exit of many bewildered audience members at its 1969 Proms premiere. Aware that he was “burning the candle at three ends at least”, and perhaps shaken by the extreme reactions to his music, Maxwell Davies retreated to the wilderness. In 1970, he visited the Orkney island of Hoy and decided that he would live there.

He immersed himself in Orkney history and culture, and struck up a close friendship with the Orkney poet George Mackay Brown. It was during his early Orkney years that Maxwell Davies started composing in more conventional musical forms. In the end, he wrote 10 symphonies, initially much influenced by Sibelius; 10 accessible string quartets known as the Naxos quartets after the record company that commissioned them; and a sequence of concertos for the principal players of the Scottish Chamber Orchestra, whose associate composer and conductor Maxwell Davies became in 1985. Separately, he wrote a neo-romantic violin concerto for the American virtuoso Isaac Stern, who was lured to Kirkwall for the premiere.

There were also three operas, two substantial ballets, music theatre works, children’s pieces, songs for choirs, and protest pieces (including an anti-nuclear cabaret, The Yellow Cake Revue). Ecological curiosity took him to Antarctica in 1997 and the result, premiered in 2001, was the Antarctic Symphony jointly commissioned by the Philharmonia Orchestra and the British Antarctic Survey.

Maxwell Davies became embroiled in Orkney life in other ways. In 2005, he was cautioned by the police for being in possession of a swan corpse. The bird, a protected species, had flown into a power cable and died; Maxwell Davies had already cooked it when the police arrived. Two years later he had another brush with authority when Orkney council refused him permission for a civil-partnership ceremony. He had set up home with local builder Colin Parkinson. However, the partnership ended badly.

Further turmoil was wrought by Michael Arnold, who had looked after Max’s business affairs for 30 years. In 2009, Arnold was sentenced to 18 months’ imprisonment for stealing more than £500,000 of his employer’s earnings. Maxwell Davies, who should have been one of Britain’s highest-earning composers, was reduced to “borrowing £10 or £20 from islanders to pay for groceries”.

Knighted in 1987, he became master of the Queen’s music in 2004, succeeding Australian composer Malcolm Williamson. “Your predecessor never finished anything,” the Queen was reported to have said to Maxwell Davies. He proved to be a huge success, using the post to champion music and particularly music education in a series of trenchant speeches and articles, and supplying the monarch with well-written pieces for ceremonial occasions.

Asked how he reconciled his political views with such an establishment position, he said: “It’s true that I once had republican leaning, but I’ve started to see that the Queen does a bloody marvellous job. She steadies things, stops them from going — dare I use the phrase? — tits-up.” He dedicated his Ninth Symphony to the Queen and, unlike his predecessor, made sure it was ready in time for her diamond jubilee, but decided against asking her to the premiere. “I don’t want to subject her to too much,” he said.

Peter Maxwell Davies. Composer and conductor. Born September 8, 1934. Died March 14, aged 81.

The Times