In Arthur & Sherlock, Michael Sims find his way to Holmes

The tale of Sherlock Holmes’s origins doubles as a biography of the young Arthur Conan Doyle.

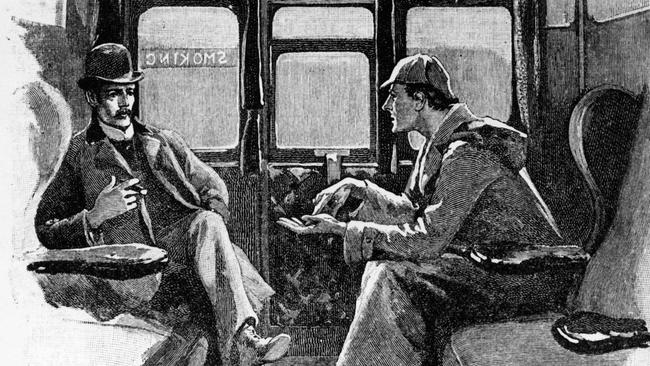

Every devotee of Sherlock Holmes knows it wasn’t Arthur Conan Doyle who gave him his signature deerstalker. It was Sidney Paget, in his unforgettable illustrations of the great detective for The Strand Magazine. Ah, but then the plot thickens. Because, in fact, it was an illustrator for the Bristol Observer who first portrayed Holmes in a deerstalker, a full year earlier — an illustrator, intriguingly, who to this day has remained anonymous.

Did Paget see these illustrations and develop them? Surely he must have done? But we would need another Sherlock Holmes to be certain. And it should be remembered that no Victorian gentleman would ever wear a deerstalker in town. Holmes sported a top hat, or perhaps a bowler, when wearing his Inverness cape against the London fog and drizzle. He was always a gentleman, albeit a bohemian one.

This is nicely conveyed in the moment he fires his gun at the wall of his apartment at 221B Baker Street — a distinctly bohemian, Hunter S. Thompson kind of way to let off steam, except that the bullet holes spell out VR, in honour of Queen Victoria. He was always a patriotic Briton, as was his bluff, tweedy, no-nonsense creator, Conan Doyle; not an intellectual, and certainly not a sensitive arty type, but surely a genius.

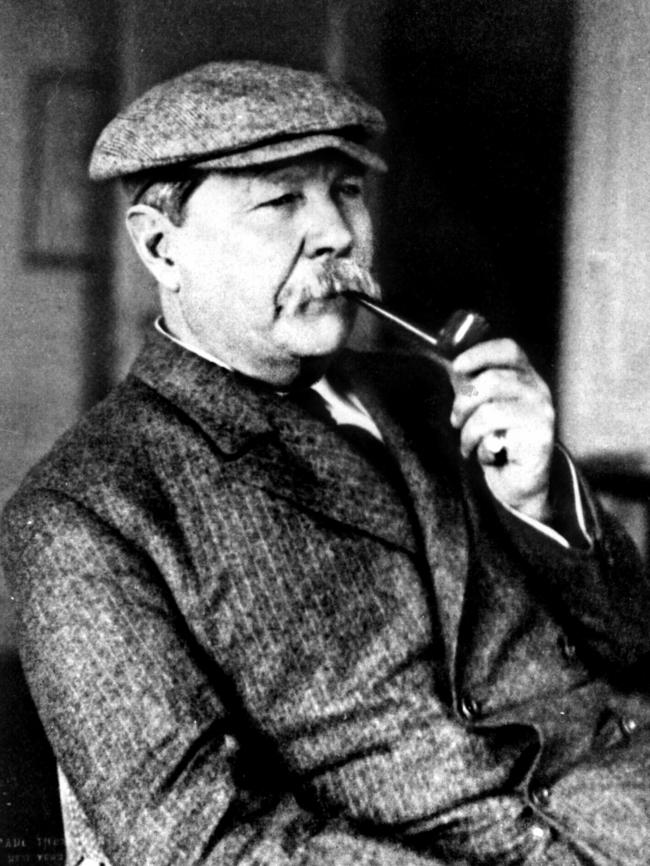

Michael Sims’s Arthur & Sherlock seeks to follow the clues and trace the evolution of Holmes in Conan Doyle’s imagination. (Another thing: Conan Doyle’s surname was just Doyle. But the grander Conan Doyle has stuck, because it sounds so much better.) The book is brimful of these kinds of Holmesian arcana and minutiae. It also works as a sketchy biography of the young Conan Doyle and how he found his way in the world, from his beginnings as a poor but hardworking Scottish doctor to a highly acclaimed writer of irresistible tales of crime, travel and adventure.

We learn much about Conan Doyle’s favourite reading. He adored Walter Scott and early westerns, and perhaps began to develop his first ideas about Holmes from the work of Edgar Allan Poe, whose fictional detective is Inspector Auguste Dupin in the brilliant, deeply creepy short story The Murders in the Rue Morgue (1841). Another fictional forerunner was Wilkie Collins’s Sergeant Cuff in The Moonstone (1868) and, of course, Inspector Bucket in Bleak House (1853) by Charles Dickens — who, like Conan Doyle, was always fond (sometimes obsessively fond) of reading crime reports and ghoulish accounts of grisly murders.

In fact, Sims goes further back, to an intriguing example of early crime detection in Voltaire’s philosophical tale Zadig (1747), to the redoubtable Dr Johnson and his real-life solving of the Cock Lane ghost mystery (an “imposture”, as Boswell triumphantly concluded), and even to the prophet Daniel in the Old Testament.

Much as he respected his predecessors, though, Conan Doyle wanted to do it differently, scientifically — and he wasn’t going to give his creation a giveaway name, as Dickens liked to. No Inspector Sharp or Ferret, he joked. He found the name Sherlock in the stories of Sheridan Le Fanu, among other places. The detective’s original name for a while was Sherrington Hope, which has a certain ring to it. John Watson for a time was Ormond Sacker, which would have been disastrous. Sounds like a con man from Kansas City.

But the greatest inspiration for Holmes, as we all know, was Conan Doyle’s teacher at Edinburgh medical school, Joseph Bell, whose method of diagnosis by startlingly close observation of his patients meant, for instance, that he could deduce instantly that one of them worked in a linoleum factory across the Firth in Burntisland — from her posture, the calluses on her hands and the traces of mud on her shoes and clothing.

A devout Christian, Bell was fond of quoting the Bible: “He that hath ears, let him hear.” And when he found himself in the peculiar situation of being immortalised as Holmes while still very much alive and working, he proved scrupulously modest and supportive of his former pupil.

Sims’s brief book doesn’t cover everything. There is no mention of Mycroft Holmes, Moriarty or Mrs Hudson, and it never pretends to be a full biography of Conan Doyle. A throwaway reference to “the ill-gotten British Empire” made this reviewer bristle, and certainly would have annoyed Conan Doyle, who “found nothing more inspiring than a vision of a stout-hearted soldier marching into battle against the odds”. At school he had memorised all 70 verses of Macaulay’s Horatius, and wrote a book in defence of Britain’s conduct during the Boer War. He was absolutely a man of the Victorian age.

However, Arthur & Sherlock does offer many intriguing insights into Holmes’s evolution, and still portrays what a decent, admirable figure a “man of the Victorian age” often was.

Conan Doyle emerges as a bluff, broad-shouldered, boyish figure with a hearty laugh. He loved hiking in the Alps and was one of the first Brits to try skiing, on long skis made of elm. He loved boxing, football and cricket, played in goal for Portsmouth, and once bowled out WG Grace.

His love of adventure led him on a whaling expedition to the Arctic, and to West and South Africa, but he also had a schoolboyish sense of justice and support for the underdog. When he came across a thug beating up a woman in Southsea, he intervened briskly and sent the fellow reeling off. A few days later, the man appeared in his surgery for treatment, not recognising him. Conan Doyle recognised him, though, treated him, “charged him a pittance, and sent him on his way”.

For all his bluffness, he could quite happily spend an evening with Oscar Wilde (he did so once at the Langham Hotel in Marylebone) and get on famously. The two men fell to talking about how wars would be fought in the coming years, and Conan Doyle never forgot Wilde’s words, in his extraordinary, sonorous delivery: “A chemist on each side will approach the frontline with a bottle ... ”

Conan Doyle also coped with great tragedy, from an alcoholic and often insane father to a beloved wife who died young of tuberculosis. His later fascination with spiritualism and a longing to contact the dead was no doubt driven by both experiences.

This short study is a stimulating contribution to our never-ending fascination with Sherlock Holmes himself, and, even more perhaps, his genial creator.

Arthur & Sherlock: Conan Doyle and the Creation of Holmes

By Michael Sims

Bloomsbury, 256pp, $29.99

THE TIMES