Hi-tech cold war between China and the West can only end in conflict

The West has been too complacent about China’s mix of Big Brother and Big Data.

The geopolitical row between the US and China, the great schism of our times, has become personal.

The man at the centre of the storm, grizzled Ren Zhengfei, was trying to soft-sell his giant tech company Huawei at the Davos talkfest the other day as if the world was experiencing little more than a mild bout of indigestion.

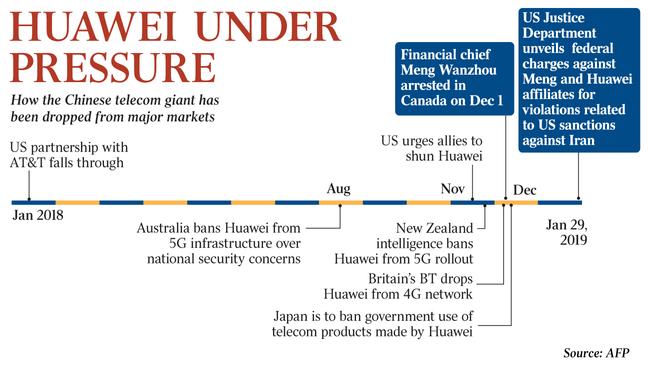

Yet his daughter Meng Wanzhou is wearing an electronic tag as she fights extradition from Canada to the US.

A Huawei employee has been arrested for spying in Poland and, across the globe, countries are working out ways of preventing his company’s devices being used to snoop on smartphone users.

Perhaps Ren was cheery because his other daughter, Annabel Yao, has made a social splash at a debutantes’ ball in Paris. Or perhaps he knows something we don’t about how the Chinese-US relationship will unfold in the coming months.

There’s deep uncertainty in the West about dealing with a country that seems to embody a marriage between Big Brother and Big Tech. The initial fear that US President Donald Trump would ratchet up the trade dispute with China’s Xi Jinping hasn’t gone away. A Chinese delegation turned up in Washington last week but there is still a real possibility that the 10 per cent tariff imposed on $US200 billion ($275bn) worth of Chinese steel and aluminium will be increased to a crushing 25 per cent by next month unless a deal is struck. That would be a devastating blow to business confidence everywhere.

Crucially, though, Trump may shift his full attention to the battle for hi-tech supremacy. The scrap with Huawei, the world’s largest telecommunications equipment maker, is already pretty rough. But many now expect an executive order from the White House that would in effect ban the use of Chinese equipment in strategically important telecoms networks.

At the moment Chinese kit is only excluded from government networks.

That’s all part of a shock-and-awe negotiating approach that involves not only tariffs, the scrutiny of Chinese investors and action against hackers but also a large dollop of Trumpian rhetoric about the way Beijing is “ripping off our country”.

That addresses core voters in the US but also the fundamental anxiety that China is accelerating on all fronts to supplant America as the sole superpower.

As a result it is never quite clear whether the US administration is acting out of protectionist motives or national security.

The blurring is deliberate. Trump, says his National Security Adviser John Bolton, is aiming not only to balance trade and ensure that China plays by established rules “but also to prevent an imbalance in political/military power in the future”.

Huawei, with its advanced research into fifth-generation mobile telecom networks, 5G for short, is Trump’s bugbear precisely because it is ambiguous about whether it serves its customers or the Chinese state.

It is a private company and a national champion, all too aware of Beijing’s 2025 target of closing the hi-tech gap with the West. The policy calls for domination of industries such as robotics, information technology and electric vehicles. Huawei is doing its bit with 5G, whose high-speed transmission will underpin smart cities and ease the way towards the “internet of things”.

Every government department is getting ready to adapt to 5G: in road and rail management, in the supply and value chains, and above all in the security establishment.

The routers and switches that come with 5G, the constantly updating software: all this creates vulnerabilities that can be exploited. The flow of information could be monitored or tampered with by whoever controls the networks.

As the tech revolution rolls on in China, gathering speed, so the range of possibilities for hostile Chinese action grows.

Last year it unrolled an artificial intelligence chipset: computer chips that will allow smartphones to use AI to recognise faces and interpret languages at very high speed. That could be adapted for military and security police use.

The mopping up of stolen or bought-in foreign technology almost always ends up profiting the Chinese defence effort.

There is now, says William Hannas, co-author of Chinese Industrial Espionage, “an elaborate, comprehensive system for spotting foreign technologies, acquiring them by every means imaginable, and converting them into weapons and competitive goods”. The US Council of Foreign Relations says the 2025 Made in China master plan represents “an existential threat to US technological leadership”.

As far as the Trump administration is concerned, Huawei is a nest of spies allowing agents to operate within its ranks, nabbing intellectual property and, because of its fuzzy relationship with the state, possibly opening a back door on its products to let data be siphoned off by Chinese intelligence agencies.

One of the charges being lodged by the Department of Justice against Huawei is that it stole tech known as Tappy — a system that mimics human fingers on keypads to test the durability of phones — from a US company.

Ren denies his company is a cover for spies. “I support the Communist Party of China,” says the former army officer, “but I will never do anything to harm any other nation.”

His daughter Meng also denies US accusations that she used company affiliates to supply equipment to Iran, thus violating sanctions.

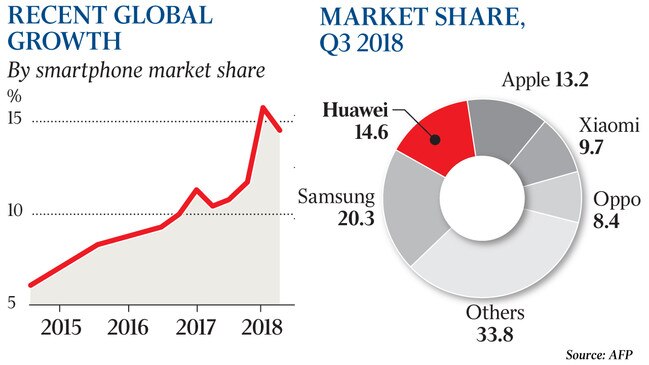

The contention of Huawei is that it is not just in the Samsung and Apple league (it has supplanted Apple as the second-biggest producer of smartphones) but has similar ambitions to be a free-thinking knowledge hub.

Ren has just overseen the construction of a new campus outside Shenzhen with buildings that try to replicate the architecture of university cities such as Oxford and Heidelberg. Sadly, there’s not much free thinking going on.

There are almost certainly more communist spies in situ than there were even in the Cambridge of the 1930s.

The fact is there have been suspicions about Huawei and other Chinese concerns for well over a decade. Yet Western politicians have brushed them aside or considered that the security risks were worth taking in return for a prosperous long-term connection with the fast-growing Chinese economy.

In 2009, according to Edward Snowden, officials from his National Security Agency mounted Operation Shotgiant, which targeted Huawei, netting internal documents, Ren Zhengfei’s email, a list of 1400 customers and the secret source code for certain Huawei products. The point was to discover something directly connecting Huawei with the Chinese army, but no conclusive evidence could be found.

Another aim was to find a back door into Huawei, allowing the NSA to conduct surveillance within the company. Again, it is unclear whether this was successful. One thing is clear, though: the Obama administration already had strong suspicions about Huawei and plentiful evidence of Chinese hacking when it struck an agreement with Beijing promising to stop digital theft for commercial advantage in 2015.

Hacking activity diminished for a while but this was more to do with a reorganisation of China’s cyberwar machine. The effect on the administration was to lull it into a false sense of security about China’s offensive, even though the military was quite evidently going through a modernisation surge and research-and-development budgets in civilian society were soaring. President Barack Obama announced a pivot to Asia knowing that the Chinese were burrowing into the US business world.

The wheel is turning against Beijing as it overextends, nudging some of its Asian soft-power beneficiaries into debt traps. And, as its growth slows, its lustre is dimming in the West too.

There have always been two sides of the argument (three if you count the mercantilists after a bag of yuan, four if you haul in the “America bad, China good” crowd) on Beijing as a partner.

The first school reckons that China is simply too large to be wished away and that there really is a way of ensuring that it does not get into mischief.

“Trust but verify,” says Alan Woodward, a leading cyber-security expert at Surrey University. “It’s correct to suspect China but not reject them out of hand. Why? Well, they are coming up with some innovations that we are not in the West. We could end up shooting ourselves in the foot.”

The second school comprises the large majority of the intelligence community, which, without any prodding from Trump, is happy that the naivety and inattention of the Obama years has passed and turned into something altogether more hard-nosed.

For Alex Younger, head of MI6, 5G and Huawei is something that should be assessed carefully rather than waved through because of the sheer pace of change.

“We need to decide the extent to which we are going to be comfortable with Chinese ownership of these technologies,” he says.

The exact shape of the Chinese challenge will take proper shape only in about five years, says one former official.

“The Chinese are spending big on high-speed quantum computers and with the help of satellites could allow their intelligence services to create highly secure encrypted communications that could be a war-winning breakthrough,” the officials adds.

Eric Schmidt, former chairman of Google, says China will have caught up with the US on AI by 2020, “be better than us by 2025 and by 2030 dominate the industries of AI”.

Which, of course, include drones and self-driving cars.

As Kai-Fu Lee, former head of Google China, suggests, it could be that the US and China settle into a hi-tech duopoly on AI, linking companies like Google and Facebook to Tencent and Alibaba. China will always be big on data; America’s top universities are difficult for China to match.

“The US and China dominate probably 80 per cent of the talent, and at least more than the majority of the data.”

A duopoly is probably wishful thinking (Lee has a book to sell: AI Superpowers) but there are optimists out there in the tech and think-tank worlds. Why, asks one Norwegian academic, should the US and China be hurtling towards war on the basis of a historical hypothesis about the inevitable clash between an incumbent and rising great power?

Why could not China and the US reach a stable equilibrium such as the one that was more or less maintained between the Soviet Union and the US?

The simple answer is that the technology arms race that is only just gearing up won’t allow it. The Cold War never quite turned hot because frustrations were vented in proxy conflicts and because of the terror of mutual nuclear destruction. Spheres of interest were respected. Arms control accords eased tension.

But the fifth generation of technology is being developed without laws or international understandings. When weaponised, it can be used without leaving a trace. How can you deter that? Power grids are the softest of targets; every sprawling city could be open to paralysing cyber-attack. That’s why the West needs to find a way of competing with, and containing, Big Brother with Big Data.

The Times