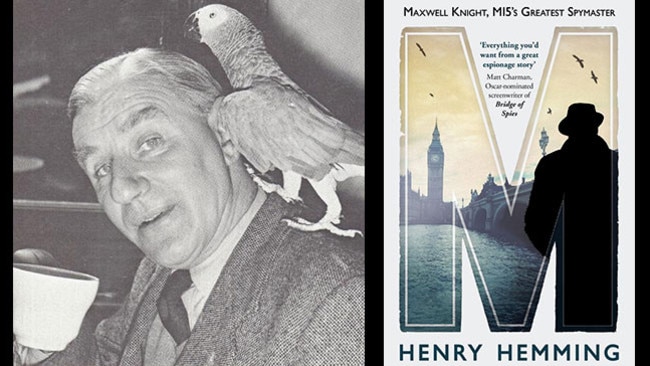

Henry Hemmings sheds light on MI5 spymaster Maxwell Knight

Maxwell Knight was a legendary spy-runner who became a TV celebrity associated with wildlife shows.

Intelligence officers and those who share London flats with pet bears named Bessie are alike off-piste human beings. If a man who is both also declines to consummate any of his three marriages, writes atrocious thrillers and attends seances with the satanist Aleister Crowley, he may reasonably be characterised as unusual.

Maxwell Knight, as Henry Hemming recounts in this excellent biography, spent 30 years in the service of MI5, and became an agent-runner celebrated throughout the tiny British secret world. Then, for the last seven years of his life, he became one of the first generation of television celebrities, contributing to a host of wildlife programs tales of relationships with snakes, marmosets, mongooses, cuckoos — and Bessie.

He once sternly lectured a wife about the importance of domestic hygiene: “Bottles, teats, tubes and mixing dishes must be washed after each meal. Failure to do this will mean sickness and possibly death.” He was here not concerned with the welfare of babies, since fortunately he never had any, but of monkeys. When he died in 1968, David Attenborough and Peter Scott headed the contributors to a wildlife memorial fund established in his name.

Hemming has done a terrific job of unscrambling Knight’s muddled life. Born in 1900 into the improvident upper-middle class, by 1923 he had already endured a brutal naval education, a spell as a London jazz groupie, expulsion from the family circle and dalliances with all manner of animals. “He handled them brilliantly,” said a cousin. “They came to him easily, trustingly.”

He was eking out a living as a Putney school games teacher when approached by George Makgill, an industrialist who ran a private intelligence organisation, with a proposal that he should penetrate the British Empire Union, and later the embryonic fascist movement.

This Knight did with such enthusiasm that he became not merely an infiltration agent but apparently a genuine fascist who participated in the kidnapping of the communist Harry Pollitt, the trashing of the reds’ Glasgow offices, and probably other excesses as well. Hemming grasps an issue critical to interpreting this era: in the decades following the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, the propertied classes became so terrified of communists that, until the last gasp before World War II, many were much less dismayed by fascists than they should have been.

Knight went from working for Makgill to presiding over a pub on Exmoor. He was then recruited to serve MI6 and MI5, no longer flirting with fascists, but fulfilling the more congenial task of penetrating the communists. He proved a superb recruiter and runner of agents, notably Olga Gray. She became a secretary at party headquarters, and was a key figure in the 1938 smashing of a Soviet spy ring at Woolwich Arsenal. This was Knight’s finest hour.

It is one of the many curiosities about the man that, while hopeless at the business end of marriage — Hemming writes that “sex seemed to scramble his radar” — he was wonderfully successful at managing professional relationships with women. Knight wrote:

I am no believer in ... Mata-Hari methods. I am convinced that more information has been obtained by women agents, by keeping out of the arms of men, than ever was obtained by sinking too willingly into them … Closely allied to sex in a woman, is the quality of sympathy; and nothing is easier than for a woman to gain a man’s confidence by the showing and expression of a little sympathy.

Among many enigmas was Knight’s friendship with William Joyce, dating from their fascist days, which in 1939 caused him to tip off this Irish-American that he was about to be arrested, in time for flight to Germany, where he became “Lord Haw-Haw”. Knight’s last coup for MI5 involved Anna Wolkoff, whom the British arrested in 1940 along with Tyler Kent, an American embassy officer who was passing secrets to the Germans. Thereafter, though Knight became a legend to a new generation of MI5 and MI6 personnel, including David Cornwell (later the author John Le Carre), the times left him behind.

Dick White (MI5 director-general, 1953-56) distrusted the old boy. A colleague described Knight’s section as “deplorable”, both for its disorganisation and the extravagance of the illicit couplings among its staff. But he remained on the payroll until 1961, after which he betrayed to the world no hint of his past save that he called a pet otter Olga and a Cairn terrier Kim.

His first wife died of an overdose of barbiturates and his second divorced him for non-consummation. In 1944 he married Susi Barnes, a colleague in MI5’s registry, with whom he seems to have rubbed along well enough, because she did not care for sex.

Desmond Morton, another spooky figure who had dealings with Knight in the 1930s, described him approvingly as “very discreet, and at need prepared to do anything, but … at the same time not wild”. That depends on what one means by wild. It is hard wholly to applaud Knight, and Hemming over-eggs the pudding by dubbing him “the greatest spymaster”. The suggestion that he inspired Ian Fleming’s M seems justified only by their common initial.

Knight did excellent work penetrating the Communist Party, and has provided material for a fluently written and highly entertaining biography. But few of us would have thought it prudent to go into the jungle with a man so frankly weird, and likely to be on first-name terms with the anacondas.

Max Hastings’ books include The Secret War: Spies, Codes And Guerrillas, 1939-45.

M — Maxwell Knight, MI5’s Greatest Spymaster

By Henry Hemming

Preface, 400pp, $49.99 (HB)