Ennio Morricone, film composer for Sergio Leone and Tarantino, refuses to retire

The legendary composer of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, among other films, returns for a Tarantino western.

People who interview Ennio Morricone — which generally happens at his lavish apartment in Rome, overlooking the marble extravaganza of the Piazza Venezia — are issued with a sheet of instructions.

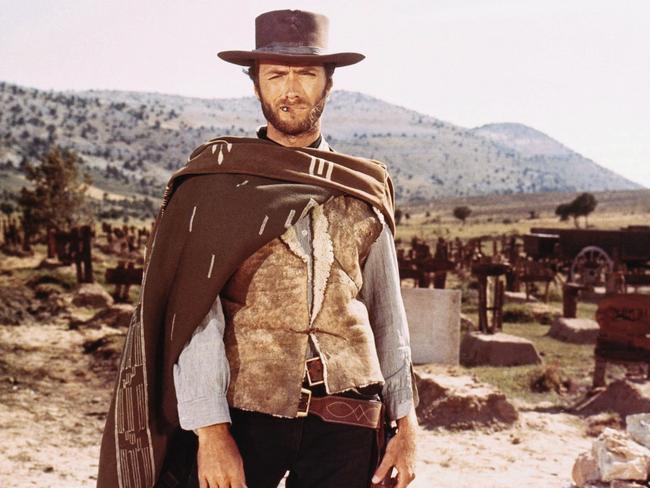

You are to address the 86-year-old composer as “Maestro”. While he’s happy to talk about the groundbreaking work with Sergio Leone (A Fistful of Dollars, The Good, the Bad and the Ugly: “Wa wa-waaaah”, etc) that established him as a giant of film music in the mid-1960s, it’s best not to start with this.

Other no-nos are “boulevard/small-talk questions about favourite directors, pets, etc, because he does not like superficial interviews”. Don’t mention the war, either: Morricone grew up in a Rome that was occupied by the Nazis, then the Americans. Finally: “Under no circumstance move furniture or other objects around. It will really upset him.”

If this makes Morricone sound like a cantankerous egomaniac, well ... he certainly doesn’t suffer fools; nor does he seem overburdened with humility, especially when his interpreter, Gioia Smargiassi, translates what he says in the third person ("Maestro says X”, “Maestro thinks Y").

The main impression I leave with, though, is of a man of courtesy and mischief who happily discusses the war, his other soundtracks (the epic, globetrotting score for The Mission, the lush, sad one for Cinema Paradiso) and why he hates the term spaghetti western ("Because it’s not a food!") without any affront to his dignity. The only time a hissy fit beckons is when I suggest that he fell out with Quentin Tarantino, whose forthcoming film, The Hateful Eight, he has scored. A post-Civil War western about strangers stranded in a stagecoach inn, and starring Samuel L Jackson and Kurt Russell, it’s evidence that he is hanging on to his seat at the top table, 50 years on.

Tarantino has used Morricone’s music in films including Inglourious Basterdsand Django Unchained, but their prospects of reuniting seemed remote when Morricone was quoted in 2013 as saying that the director “places music in his films without coherence” and “you can’t do anything with someone like that”.

Opening with such an inflammatory subject would be suicide, though, given that Morricone is such a stickler for interview etiquette. So we start with niceties, and I’m careful not to touch the furniture. Although, as Maria — his wife of almost 60 years, with whom he has four children and four grandchildren — leads me through the Old World opulence of their apartment, part of me itches to shake the planet-sized chandelier or ruffle the tapestry depicting The Rape of the Sabine Women.

Morricone looks frail but alert, dressed in polo shirt, slacks and chunky glasses, his remaining hair combed across his head. In a hoarse whisper worthy of a mafia don, he apologises for not getting up from his armchair; he fell on holiday and broke a femur. He and his publicists emphasise that it hasn’t stopped him from fulfilling his duties. A few days earlier he conducted (seated) a concert in Verona; apparently it was “a full house and a great success”. Does he hope to be standing again by February, when he conducts his work in London? A theatrical shrug. “Let’s cross our fingers.”

I take a deep breath and broach the subject of his reported comments about Tarantino. Boom! He throws up his hands and shouts, the effect of his outburst only slightly lessened by my having to wait for Gioia to translate it. “No, this is not true at all!” The quote, he says, referred to a sequence in Django Unchained in which a slave is eaten by dogs (accompanied by music from Jerry Goldsmith and Pat Metheny). “It was too much to bear,” he says, “but I never made a comment about the way Tarantino used the music. And I never dreamt of saying I wouldn’t work with him again.”

Either way, it didn’t put Tarantino off — he came to this very apartment to ask Morricone to score The Hateful Eight. “In one hour I said yes. It was the confidence, the trust.” Did Tarantino ask for a particular kind of music? He shakes his head. “Some directors have such a level of confidence in me that they don’t ask for anything in particular.”

No previews of Morricone’s score were available, but the film, he says, is “completely different from any western you have ever seen” and we should expect the music to follow suit. There certainly won’t be the eerie whistles, twanging guitars, whip cracks and coyote calls that characterised his work for Leone. “I worked really hard because I wanted to stay away from what I wrote for Sergio Leone.”

Tarantino had to come here because Morricone has lived in Rome all his life. Growing up here during the war, he says, “was not carefree. Food was scarce.” He became a trumpeter, like his father, playing in exchange for food “in the worst places ever, where the American soldiers went to dance and get drunk. I started from very low places but I learnt a lot. When I first started studying at the conservatory [the National Academy of Saint Cecilia] I had already learnt how to behave as a composer.”

After graduating, having completed a two-year harmony course in six months, he started composing for theatre, radio and concert hall. “I never thought about becoming a film composer,” he says, but he drifted into scoring light comedies and costume movies, none of which made a huge impression. Then, in 1964, Leone knocked at his door. They had first met as eight-year-olds in the same class at school. Morricone doesn’t remember anything about Leone then ("There were 30 students in the classroom") and didn’t see him again until 30 years later, when he came to his house to ask him to write the music for A Fistful of Dollars.

“I immediately recognised him, even though many years had gone by,” he says.

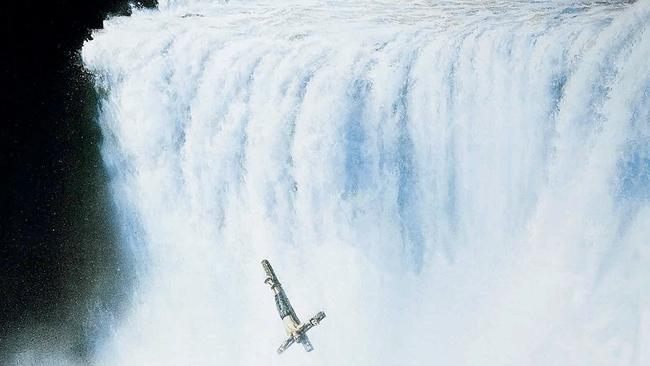

The partnership became one of the most successful in film history. Morricone’s score to Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West has sold about 10 million copies; the main theme from The Good, the Bad and the Ugly became a No. 2 hit, and that film’s other most famous piece, The Ecstasy of Gold, has become iconic — Metallica have it as their intro music at concerts.

Woe betide anyone who pigeonholes Morricone as a composer for cowboy flicks, though. He points out that, of his huge body of work (more than 500 scores for film and television, songs for Joan Baez and Morrissey, a less-heralded string of piano concertos, symphonies and choral music and even an opera), “just 8 per cent has been composed for westerns. But everybody says I’m a western composer.” Does that annoy him? Another shrug. “Many people are quite ignorant; they don’t know the full range of my work.”

Given his reluctance to return to westerns, his recruitment by Tarantino seems like more and more of a coup. When Clint Eastwood, another Leone alumnus, asked him to score two of his early films as director, “I said no out of respect for Sergio Leone [who died in 1989]. I didn’t want to do the music of a western that wasn’t directed by Leone. And then, of course, Clint [or “Cleent”, as he pronounces it] never called me again. Then over time he started writing his own music.” He chuckles. “To be honest, he’s a much better director than composer.” Would he say yes if Cleent asked again? “Yes, I’d be very pleased.”

Morricone clearly loves these august directors making pilgrimages to see him. Would he ever ask to work for a director? He looks appalled. “No!” One of the reasons, you suspect, that filmmakers think so highly of Morricone is that he is seen as a rebel who resisted overtures to move to Hollywood and refused to learn English. The first part is correct, he says, but not the second. “I never refused to learn English. When I was young I didn’t have the chance, then when I was older I didn’t have the time. In fact, it’s one of the things that I regret the most because everybody else speaks English and I always need somebody to help me.”

Did his distance from Hollywood harm his Oscar chances? Nominated five times, he has never won, unless you count the honorary award in 2007, which he clearly doesn’t. “I don’t think so. The fact that I didn’t win for The Mission [in 1986] was a big mistake on the part of the Academy, but it’s not because I didn’t go to Hollywood or learn English.”

That he lost out to Herbie Hancock for Round Midnight is “a quite delicate issue. At that time it was almost impossible for a black man to win an Oscar, so maybe it was a political decision,” he says. “I remember that the audience were quite upset by the fact that I hadn’t won.”

It’s been downhill since, according to the film writer David Thomson, who recently lamented the decline of the movie score. It’s a view that Morricone has sympathy with. “Maybe the potential decline is down to the fact that directors and producers tend to hire amateurish composers because they cost much less, rather than real composers.”

That, he says, has made things tricky for his son Andrea, who followed him into film composing. “I tried to make him change his mind because I knew it was a very difficult road he was going to walk. He insisted and he became a very good composer and conductor. However, he struggles a lot because he is a real composer and the industry is dominated by amateurs.”

As he edges towards 90, he insists that he never thinks “in terms of retirement, but I think that maybe I should dedicate more time to symphonic and chamber music. That was my first idea when I was a young composer.” Does he see it as higher than film music? “It’s not a question of higher or lower, it’s that with film music the main piece of work is the film, then comes the music. With chamber and symphonic music it’s only me and my music.” That, clearly, is when this maestro is happiest.