Driver Susie Wolff, team principal Claire Williams new F1 breed

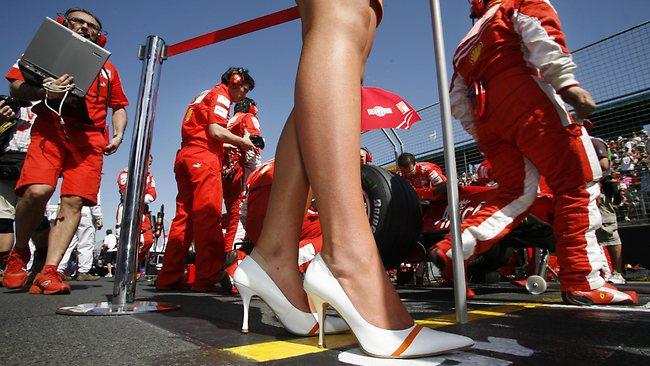

AFTER years of grid girls, blatant sexism and being stuck in a '1970s Playboy time warp', Formula One is taking women seriously.

THE surprising thing about Sir Stirling Moss's recent remarks about women not having the mental strength to cope with wheel-to-wheel racing, was not their wildly sexist nature.

After all, he was talking about Formula One, a sport where women in Lycra and PVC are still draped over drivers and cars, where the man in charge, Bernie Ecclestone, once remarked, "women should be dressed in white - like all other domestic appliances", and where the former world champion, Jenson Button, has argued that women could never drive because "a girl with big boobs would never be comfortable in the car.

And the mechanics wouldn't concentrate. Can you imagine strapping her in?".

The remarkable thing is that Moss should make such prehistoric utterances at a time when F1, for decades stuck in a 1970s Playboy time warp, is waking up to sexual equality. For the first time in the sport's 63-year history, there is a team, Sauber, with a female principal: Monisha Kaltenborn.

At the Bahrain Grand Prix two weeks' ago, Red Bull sent Gill Jones, the team's head of trackside electronics, to collect their constructors' trophy.

And Williams, one of Britain's most successful F1 outfits, with nine constructors' championships under its belt, not only employs the 30-year-old Susie Wolff as its development driver, but recently appointed the 36-year-old Claire Williams, the daughter of founder Sir Frank Williams, as deputy team principal.

"Things are definitely changing," says Wolff, speaking at the Williams' offices in Oxfordshire. She acknowledges that change is coming from a low base, with only five women having entered an F1 race, against more than 800 men, but adds: "There is a sense of expectation and as soon as you get that pressure, things happen."

If you are wondering what is (excuse the pun) driving this belated revolution apart from drivers like Wolff, and the US IndyCar and Nascar driver Danica Patrick, disproving Moss's inane arguments about mental strength, there is a clue to be found behind Wolff's high, starched collar.

"I was at a football game and a physio came up to me to ask what sport I did. He had never seen a woman with such a big neck."

She strokes the side of a neck that has grown as a result of fighting g-forces during races, and which she keeps concealed behind shirts and scarves.

"If you grab a boy and girl from the street, the boy will be better at racing. Women have 30 per cent less muscle than men. But with practice, training, women can become as good. I wouldn't do it otherwise."

The belated acceptance that women are up to the job physically - Wolff adds that drivers such as the world champion Sebastian Vettel are hardly chunky anyway - has come with another realisation, as outlined by Wolff's boss, Claire Williams.

In short, motor racing seems to have realised that excluding half the world's population is not the most commercially savvy thing to do.

"I don't want to discuss it because I don't want to give other teams ideas," says Williams, her paranoia momentarily betraying the fact that she worked in the team's communications and PR departments for a decade before being made deputy team principal in March.

She ends up discussing it anyway. "How many female brands do we have in F1? We are leveraging that possibility. We need to remember that 40 per cent of our audience is female."

Though, again, it rather betrays the low base motor racing is working from that when Wolff raced for seven seasons in DTM, the German touring car championship, her sponsors put her in a pink car for two of them.

She tried to make the best of it in the first year, knowing she was attracting girl fans who would otherwise not watch motorsport, but admits that she "hated it".

"I fought very hard to change it for the second year. It was terrible."

She rolls her eyes at the memory, cringes, and it becomes evident as she does so that she and her boss are quite different people. Superficially they have lots in common. Both grew up in motor racing: Claire, the daughter of Sir Frank; Susie, from Oban, accompanying her motorcycle-racing father to races, and at eight being bought a kart with her brothers.

Both are in relationships with people in the industry: Claire's boyfriend is a Williams race engineer ("we see each other probably more at work than at home"); Susie lives in Switzerland with her husband Toto Wolff, the executive director of the Mercedes Formula One team, and a shareholder at Williams.

Both women have faced accusations of nepotism and conflicts of interest. But of the two, Wolff is definitely the more strident feminist.

She bristles at the description of F1 as a male-dominated sport. "Do you think so? What about football?"

And she is dismissive of The Pits, the book by ITV1's former pit-lane reporter Beverley Turner, which painted F1 as a sport where female workers are routinely measured by their looks; where publicists live in fear of losing their jobs to more attractive candidates; and where the former Ferrari driver Eddie Irvine feels free to declare that "women in Formula One are only to be looked at".

"I have never been sexually harassed," Wolff insists. "To me, F1 is just one big family."

However, she admits to the challenge of being a woman in F1 - confessing annoyance at being referred to in the press as an "F1 babe" ("it's interesting that we as women are judged so much by appearance"), admitting to times of struggle ("sometimes, you think: is there anyone here who is on my side?"), and confessing she identified with many of the scenarios in Lean In, the bestselling female-empowerment book by Sheryl Sandberg, Facebook's chief operating officer.

Especially near to home were the descriptions of how women sometimes attempt to hide weakness in a way men don't, doubt themselves, and do not stand up for their rights.

"It's a small thing, but there have been many times when there hasn't been a women's toilet open at a test track, because I have been the only woman there, and instead of going to the office and demanding they open a toilet, I just use the gents. Don't make a fuss. But actually there should be a woman's toilet open."

A pause as Sir Frank, who has been tetraplegic since a car accident in the Eighties, glides past the window behind us. "I know before I did my first test for Williams, there were many people in the team who thought I couldn't do it. People who came up afterwards and said 'I thought you would spin off'."

Do male drivers take defeat at the hands of a woman particularly badly? "Much worse! I had a new team-mate last year in DTM who was a Formula Three champion, a very quick kid, and after our first test he said, 'I just can't imagine it's you in that car. You're so fast'."

What did she say to that?

"Well, I am in it, I am driving fast... so... f***..." A glance at the (female) PR who is sitting in on the interview and a change of tone.

"When I joined the Mercedes DTM team, as part of a line-up of eight, there was a big furore that I was a girl, but three years in, journalists would ask my team-mates what it was like working with a woman, and they would not know what to say. They had stopped thinking about it. Slowly things change."

If some of the other comments made by Williams and Wolff are anything to go by, the pace of change in F1 could be glacial. They may be pioneers, but both women defend F1's use of grid girls, with Williams even saying that "those girls probably have to spend quite a long time in the gym to get bodies like that. They make an effort and look nice".

Wolff defends Ecclestone who has said: "If Susie's as quick in a car as she looks good out of a car, she'll be a huge asset."

Meanwhile, though Williams says there is no reason why she could not do her job with children, it is notable that when she took over at the team, just a short while after her mother had died, she felt obliged to tell an interviewer: "I don't think anyone would be too impressed if I went and got pregnant right now."

As for Wolff, she would not continue racing if she was a mother.

"As a racing driver you have to be very selfish. I would never like to have a child at home and go off to a race meeting."

But male drivers do it.

"I don't think like that. It is what it is, and you have to make the best of the situation."

Talking of which: for all their progressiveness in recruitment, the situation at Williams is not at its best.

The team won seven drivers' world titles in the 1980s and 1990s, but last year they came eighth in the constructors' championship, and this season they have yet to score a point after four races.

Both women have their work cut out, but the pressure does not seem to hamper their ambition. Williams admits she would "love" to take over from her father one day, and Wolff says that, despite her age (people begin talking about retirement in F1 at the age of 32), she is determined to work towards a race seat.

"Driving an F1 car is such an exhilarating feeling," says the former British women kart racing driver of the year, who has also competed in Formula Renault and Formula Three.

"There is so much downforce. When I came back into the pits I knew my next goal was to get back into the car somehow."

How did it rank as a life experience?

"Up there with my wedding."

Really? Of course, lots of male drivers, in their typically macho way, say that driving an F1 car is better than sex.

"I wouldn't go that far," she says laughing.

"Not least, my husband is going to be reading this piece, so he won't be very happy."

The Times