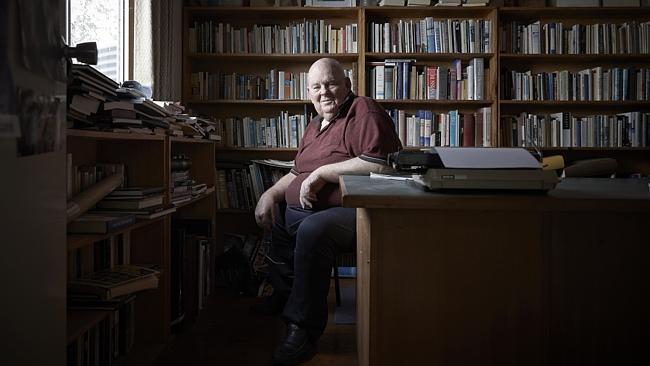

Poet in residence Les Murray

LES Murray, bard of Bunyah, bares his soul - and reveals his next great work.

Home is the first and final poem. Home is the green sofa by the lounge room windows where the poet lies resting like his father, Cecil, did all those days he spent dying in this house. His bare right foot is pale purple and swollen and skin-cracked and it twirls in circles. Nothing about his 76-year-old body is self-aware: the great white hairy belly that he exposes twice daily to jab with insulin for his Type 2 diabetes; the gap-toothed smile like black and white piano keys, sun-warped and bending.

Home is a parmesan cheese tin in the middle of the dining room table, Saxa salt, a packet of ibuprofen, TV Guide, Juanita Phillips, tomato sauce, six pairs of large blue tracksuit pants hanging on a single string clothesline; a blue-grey cat named Boris whose coy and gentle manner belies the fact he eats his prey brain first, and his wife, Valerie, in the corner armchair pencilling crosswords. Australia’s greatest living poet, nine letters, L, something, S, M, U, R, something, something, Y.

Everything about his mind is self-aware. Analysing, probing, excavating. There’s an actress’s name right now in that vast and beautiful vessel and if he can find it, if he can sink into his mind’s treacherous abyss – through the black memories filled with the mother he feels he killed and the cruel girl-women from Taree High who killed his boyhood and birthed his career – and emerge with the first and last name of that blasted actress, then there is still hope.

What’s her name? Texan. Cute. Earthy. Her elderly relatives spoke a mesmerising form of Schwyzerdütsch, Swiss-German, lived near Valerie in southern NSW. What’s her f..king name?

Home is two thin wood single-level houses built side by side on a 16ha property in Bunyah, mid north coast NSW, where the grass is not green but dry and brown. Home is the property with the yellow letterbox and silky oaks with leaves like fire and a backyard dam with a thousand pink-white lilypads where roos and goannas and snakes rest in shade for the afternoon. Home is the faint scar beneath his left nostril – his earliest memory, falling off the veranda of his boyhood shack, the long-vanished slab house that once stood a kilometre up the road towards the Bunyah Dance Hall, where a penniless dairy farmer’s only child taught himself to read at the age of nine, taught himself to grieve at the age of 12.

Home is a framed A4-sized flyer for poetry readings every second Sunday at Valona Deli, 1323 Pomona St, Crockett, California. A cheap and poorly illustrated flyer from a decade ago, the only clue here to his staggering career – six decades of “scribbling” about himself, his family, his bushland, his beloved country, his glorious God, so powerfully that The New Yorker places him “among the three or four leading English-language poets”.

“Featuring Les Murray! Australia’s leading poet and one of the greatest contemporary poets writing in English. His work has been published in 10 languages. Les Murray has won many literary awards including the Grace Leven Prize (1980, 1990) and the prestigious T.S. Eliot Award. His 1998 verse novel, Fredy Neptune, was hailed in Britain and America as a masterpiece of 20th century literature and awarded the Queen’s Gold Medal for Poetry on the recommendation of Ted Hughes.”

“That’s quite a rap!” says Valerie, as if hearing the Ted Hughes news for the first time.

“I knew privately that I wrote better than Ted, but I wasn’t as famous,” Les says.

“You weren’t British darling.”

“Hmmmmfff!” Les grunts. That sound punctuates his declarations, a throaty gut acid exclamation acknowledging points made and taken. “You know where I’ve never done a reading? Bunyah. You couldn’t do it. They wouldn’t come. A lot of the locals here are scared of being put in a poem. Because there’s no defence against it. You can’t write well enough to fight back. Hmmmmfff.”

He’s often smiling when he grunts like that. Even his bitterest words are spoken joyfully.

“Keating was a real little pustule,” he smiles about the man who once gave him a $40,000 poetry prize. “Howard was faking, lying,” he beams about the man he co-wrote a constitutional preamble with. “Germaine Greer was a fairly poisonous piece of work.” “Shakespeare was a cowering knave, a political toady, a master of spin and a brilliant poet, hmmmmfff.”

Hmmmmfff means take it or leave it. Hmmmmfff means go f..k yourself, I’ll be waiting for you right here on this green couch. “Would you like tea, soft drink perhaps?” he turns on a coin. The jolliest, sweetest, most misunderstood man to ever be labelled a right-wing left-wing conservative fascist socialist malcontent dropping “fool mouth” bombs from his bum-sagged sofa as his beloved Valerie rolls her eyes, half concerned, half proud of the fire inside her Leslie.

“I’ve always thought of NSW as, at heart, a criminal enterprise.” Boom. “Come the Second World War everybody in Bunyah could get a job. Shooting humans!” Boom. “Clive always wanted to be a poet, but he wasn’t quite good enough.” Boom.

We all have our cards marked, but I just wish Clive [James] was dying a bit later.”But he loves Clive James dearly, misses all of his 1960s Sydney University contemporaries, misses their fight. “We all have our cards marked, but I just wish Clive was dying a bit later,” he says. “He’s hurrying the matter a bit much. He, too, was an only child and, boy, doesn’t it show. Germaine was an only child [she was, in fact, one of three siblings]. And who was the other one?” He turns his head to Valerie. “The one who used to snub you as if you didn’t exist? Who was that?”

“The blond guy?” Valerie says.

“Yeah. Bit of a creep. A lot of a creep.”

They both stare at the ceiling.

“Damn, I can’t remember his name,” Les says.

A man emerges from a bedroom past the small toilet adjoining the living room. Alexander Murray is 36, tall, kind and living with autism. He’s the second youngest of the couple’s five children. He sits beside his mother and holds his trembling right hand, palm facing the carpet, in front of her face. Valerie smiles – the serenity and understanding of a lifelong teacher – and immediately cups his right hand soothingly between her two flat palms. When he took your hand, it was to work it, as a multi-purpose tool, Les wrote of his son’s autism in It Allows a Portrait in Line-Scan at Fifteen:

It does not allow proportion. Distress is absolute, shrieking, and runs him at frantic speed through crashing doors…

He can read about soils, populations and New Zealand. On neutral topics he’s illiterate.

“Arnie Schwarzenegger is an actor. He isn’t a cyborg really, is he, Dad?”…

For many years he hasn’t trailed his left arm while running.

“I gotta get smart!” looking terrified into the years, “I gotta get smart”.

“Les has finally accepted he [himself] has Asperger’s,” Valerie says.

“Having never been anybody else, I never noticed it,” Les says. He nods at Alexander. “But it’s no accident he’s autistic.” He shrugs. “I don’t mind it. People who have Asperger’s have to learn human.”

“What’s for dinner?” Alexander asks.

“Chicken drumsticks and fried potatoes,” Valerie says, rising from her corner armchair and reaching for her walking frame. She was in hospital recently for an operation on a long-troubled knee infected with golden staph bacteria. Hospital visits were complicated by the fact that, days ago, Les rolled the family Ford on a gravel road through Bunyah, wrote the car off: “My near ‘Oh f..k’ experience’.” He wasn’t wearing his seatbelt. “Don’t like seatbelts much,” he says. “But I like air bags.”

Valerie shuffles to a sideboard and flips open a book they’ve been sent, Poems That Make Grown Men Cry: 100 Men on the Words that Move Them, a collection of poems selected by men such as Ken Loach, Stephen Fry, Clive James and Christopher Hitchens. “A few of those poems made me cry,” Les says. “And we Aspergers don’t cry easily.”

Songman Nick Cave has selected Les’s poem from 1963, The Widower in the Country. “This very sad poem of loss revolves mournfully around the unmentioned death of the farmer’s wife as we follow him through his dire and ineffectual day’s work,” Cave writes. “He is that tough old Australian country man so familiar to me, just getting on with the business of life.”

He is Les’s father, Cecil.

I’ll get up soon, and leave my bed unmade

I’ll go outside and split off kindling wood

from the yellow-box log that lies beside the gate,

and the sun will be high, for I get up late now

“Who’s Nick Cave?” Les asks Valerie. “I don’t know the bloke.”

The first poem Les Murray ever wrote was penned on Christmas afternoon, 1956. Complete rubbish, he says, but touching on themes he’s explored for six decades: home, himself, his mum and dad, Bunyah, where he belongs. “Well, it all had to be solved,” he says.

Almost every poem he’s written since the mid 1960s that survived the wastepaper bin could make a man cry – tears of sorrow or joy – depending on the time that man dwells in his abyss.

No weight would he let my mother carry.

Instead, she wielded handles

in the kitchen and dairy, singing often,

gave saucepan-boiled injections

with her ward-sister skill, nursed neighbours,

scorned gossips, ran committees.

She gave me her factual tone,

her facial bones, her will,

not her beautiful voice

But her straightness and her clarity.

I did not know back then

nor for many years what it was,

after me, she could not carry.

That poem, Weights, was for his mother, Miriam, who died in 1951. “They had three more children but they died in the womb,” he says. “The last one killed my mother. It’s about that business of mine, thinking that I caused her miscarriages. She was in a state of clinical depression for the last six years of the 12 I knew her. I think she suspected my birth caused her troubles. It’s a real bugger to feel that your birth might have prevented theirs.”

He pauses. “You can become an only child by taking away their lullaby.”

Good line.

“Like a lot of good lines, it’s hard bought.”

He dwells on a poem for days, years. His genius is an ability to process the 1,025,000 words in his brain and select precisely the right one to follow the one that came before it.

Above the cat-and-mouse floor of a thin

bean forest

snails hang rapt in their food, ants hurry through several dimensions:

spiders tense and sag like little black flags

in their cordage.

The Asperger’s assists the process.

The last interior is darkness. Befuddled past-midnight fear, testing each step like deep water, that when you open the eventual refrigerator, cold but no light will envelop you.

So does his humour. The Dream of Wearing Shorts Forever. The Quality of Sprawl. Black Belt in Martial Arts.

And so do the blessings and curses of his history. Sex is a Nazi, he wrote of the Taree High girls. The students all knew this at your school. To it, everyone’s subhuman for parts of their lives. Some are all their lives.

“It was a howling bitch of a place full of bullies who enjoyed tormenting,” he says. “They realised quickly I had no common sense and no defenders. All girls, and you can’t punch girls. It really left a deep mark.”

“I used to do a lot of misbehaving in the 1980s,” Alexander shares, sympathetically, from his seat at the dining table.

“You weren’t too bad,” Les clarifies. “You only went rancid in your early 20s. But that went away.”

Les writes of his father’s 1995 death in The Last Hellos:

The knob found in his head was duck-egg size. Never hurt. Two to six months, Cecil.

“I’ll be alright,” he boomed to his poor sister on the phone. “I’ll do that when I finish dyin’.”

Don’t die Cecil. But they do...

People can’t say goodbye anymore. They say last hellos...

Snobs mind us off religion nowadays, if they can. F..k them. I wish you God.

“That one’s a litmus test,” he says. “If you like that one you’re probably a decent person.”

After 30 years’ scribbling in Sydney and across the world, Les and Valerie moved into this house in 1985 to care for an ailing Cecil. “He had a good last 10 years of his life, but he never recovered from his early misfortunes,” Les says. “He was wreckage after Mum died. He would break down while he was cooking in the kitchen, start weeping. He was rubbish for 10 years. His bravado went in half an hour.”

Valerie looks to the couch where her father-in-law would rest in his final days, in the middle of the lounge room, as a swirling family existed around him. “I remember him in here and me saying, ‘Do you find it hard to have us here quarrelling and making a lot of noise? You know, taking away the calm of being here?’” Valerie says. “And he said, ‘Not at all. I love every minute’.”

We’re all human and, therefore, deeply inconsistent.”Les sighs. “We’re all human and, therefore, deeply inconsistent.”

He’s spent 76 years learning human and that’s as clear a summation of his study as any. In a single sitting he might mention 30 individuals he’s known – literary icons, politicians, contemporaries, editors, publishers, relatives, close and distant – most of them flawed. Good people are rarely what they seem and bad people are exactly what they seem. Most humans let him down in some way, betray him, betray their country, betray themselves. Valerie is consistent. Alexander is consistent. Juanita Phillips, talking now on the nightly ABC television news, is consistent. Susan Butler, editor of the Macquarie Dictionary, is consistent. “What edition Macquarie do you have?” he asks.

“The green one,” I say.

“They’re all green.”

He scans my face momentarily, studies my clothes, my shoes. “You’d have edition five,” he says.

In the entertainment cabinet by the TV are dolls that Valerie made in a creativity workshop. There’s a beautiful doll bearing Alexander’s genuine likeness, what Les calls his son’s “strange ethereal otherworldly innocence”. There’s another doll based on Les’s face, a passable representation of his years and mileage, if also a Hammer Horror prop; the real face now grimacing at a news report on Tony Abbott. “I’m trying to lean out of politics altogether,” he says. “In my lifetime it’s been mostly a curse. I’ve just found it such an unpleasant, compulsory and savage world that it sickens me. That’s true of all the political sides. I don’t like any of them.

I’m trying to lean out of politics altogether. In my lifetime it’s been mostly a curse.”“Australia’s coming out of an awful period. And not coming out all that quick. It’s a period in which the elites have decided to despise the Australian. You know it well when you live in the country. You are despised by the city’s intellectual classes. The only licensed bush person is an Aborigine. It’s been much more pronounced in the last 40 years. I always get the feeling there’s something fake about it. Then when I hear the Australian elites going on about the Anzac, I feel like throwing up. I don’t believe a word of it.”

The topic has stifled him. He needs to move his bones. He rises from his couch and pads outside to water his vegetables. There’s a mower sitting by his tin shed. A wooden crucifix rests against a side window beyond his small square vegetable garden. Trees tower and ramble behind him, more and more surviving his axe the more his swing slows.

“A lot of people go mad in the bush,” he says. “Farmers knock themselves off.” He shrugs. “I’ve always had too much work to do.”

He trains his hose on the vegetables. “You often don’t know you have depression when you get it,” he says. He got it for seven years, starting roughly around 1988, a period he calls The Big Sick that coincided with an intestinal abscess that led to liver surgery that led to a near-death three-week coma in 1996. He wrote of The Big Sick in a 1997 book, Killing the Black Dog. “I had a bad year and a half of it and it largely went away and it just became latent. And then it came back.” He adopts a demonic voice. “It said, ‘My name is Depression and I’m here to give you a badddddddd time’.” His hands are wringing something invisible, his mind. “I never killed the black dog. You can’t. Nobody ever kills the black dog.”

He wrote furiously through it, wrote about animals and plants and things that didn’t have to breathe to exist. “I was crazy as a loon at the time. It was a great relief to go off into the soul of a kangaroo or a bear for a while. It was a relief from being me.”

Not even Les Murray can write a love poem about Valerie that could adequately describe how grateful he is to the woman who stood beside him through it, the panic attacks, the depressive fits, the bouts of extreme hypercondria.

“Doctor, look at this, am I dying?”

“Les, it’s a cold sore.”

“I was always just imagining it,” he says. “But the imagination can drive you clean mad.”

Imagination. He could well be the greatest poetic imagist alive today because he sees things in his mind others can’t. But he sees too many things, he complicates and excavates. He doesn’t say, “I love you, Valerie, thanks.” He looks deeper. He writes her a four-page poem about one of her passing interests – “yellow ware”, big yellow roadside machinery. He crafts her an epic masterpiece called Machine Portraits with Pendant Spaceman. And the love is in the thought and effort he puts into the work. Every machine has been love and a true answer.

I only ever write about the inner secrets of love. What a deep dark thing it really is.”“I only ever write about the inner secrets of love,” he says. “What a deep dark thing it really is. Anybody can make a song and dance out of it. But to get out how it really is, is a deep dark business. I’ve only written a little bit about it, it’s such a complex and dark and risky thing.

“If love shows you its dreadful face before it shows you its beautiful face then you will be cursed. It showed me its dreadful face before it showed me its beautiful face.”

Dinner’s ready. We eat Valerie’s chicken drumsticks, grabbing the bones with our fingers, running them through her pan gravy.

Brown gravy, brown gravy,

should be sold by the bottle

Drink savoury not sickly,

let your clothes catch the dottle

We drink wine into the night, a red he likes called Swings & Roundabouts, with a toast to nothing because nothing matters in the here and now except Valerie, Alexander and the scribbles. The cracks in the kitchen tiles don’t matter; the peeling paint on the walls; the weeds outside, the dishes piling up inside, the trail of dried tomato seeds running along the pocket of Les’s blue polo shirt. We listen to classical music and speak of cane toads, louvre windows, David Gulpilil, a camera that can focus at any distance, Kyoto, Okinawa, atomic bombs and the strange ethereal otherworldly innocence of Juanita Phillips.

“A dear little lady,” Les says.

“Why’s she dear?” barks Alexander.

Rich in spirit, Les explains, if not dollars.

Les drinks from the same mauve-coloured wine glass he’s drunk from for half a century. “I’ve consumed a large amount of wine through this glass,” he says. Much of it with Bob Ellis. Alexander and Valerie go to bed and we consume some more. I tell him I liked his piece about his long-time hearing loss, Hearing Impairment, where sentences follow preceding sentences in anagram, showing how all humans hear things differently.

“What?” he says, folding the top of his left ear.

“I said, ‘I love your poem about hearing loss’.”

“Wassat?” he winces, leaning closer, half-smiling.

We talk about the constitutional preamble John Howard asked him to co-write in 1998, a tamed and watered-down version of which was rejected by public vote. “I did it, like a fool,” he says. “I thought, that’s enough for writing for the government. Never again.”

We talk about the great Sydney Push and his dear old Bondi roommate Ellis and pigeons and Sicilian gangsters and why being a national treasure doesn’t pay the bills and why it only takes a small box to fill a poet’s national treasure.

We talk of the sometimes fractured relationship he’s had with his eldest children, Christina and Daniel. And he loses his bravado. He stares into his wine glass, one year younger than Christina, who’s 51.

“I was not all that patient with the eldest children, hmmmmfff. I learnt to be good to our children with our third. Not our first. I was not used to children. [Third child] Clare was such a charming little girl that she brought me around. It was good that she did because Alexander was next and he was a real test.” His voice softens. “Christina and Daniel, the first children, were very nice children but I was less patient with them than I should have been.” He sips, shakes his head. “And there’s no correcting that.”

“Can you tell me about The Future?” I ask.

I mean the poem.

It is said we see the start.

But, from here, there’s a blindness.

The side-heaped chasm that will swallow all

our present

blinds us to the normal sun that may be imagined shining calmly away on the far side of it

I also mean this house. Him. The future for Alexander when his parents go. But he doesn’t respond. He takes his last swig of Swings & Roundabouts. “If I don’t go to bed I’ll turn into a pumpkin,” he says.

Home is Valerie’s carefully folded bed sheets in the spare room. Home is a can of Mortein standing on an ironing board. Home is a plastic-seat support frame permanently fixed on the hallway dunny. Home is Les’s crispy bacon and eggs for breakfast.

“All right,” says Valerie, entering the living room on her walking frame. “I think you three can go get us some supplies.” Alexander rubs his nose furiously, parts his hair.

“What do we need?” asks Les.

“Milk, butter and bread,” says Valerie.

“Butter and bread,” says Les, nodding.

“Milk, butter and bread.”

“Milk, butter and bread.”

“And some Equal sweetener.”

“What?”

“Milk, butter, bread and some Equal.”

“Milk, butter, bread, Equal. OK.”

Les puts his shopping hat on, the hat’s brand name stretching across its back: “Fat Face.”

We go to his car. “Wait,” he says. “I wanna show you something.”

We walk to the single-level dwelling opposite the main house. This is Les’s writing house. There’s a fireplace built out of painted ceramic tiles collected from around the world. On the mantelpiece is a sign saying, “Private poetry, trespassers welcome.” There’s a crucifix that was taken from his father-in-law’s coffin. By his office door is an old photograph of his mother, 23 and beautiful. Next to that is a photograph of Cecil, 80 and beautiful, and stout and sad.

His office walls are covered in poetry books. There’s an A4 piece of paper above his desk with a word roughly scribbled on it: “NO!” In the middle of his desk is an old Brother typewriter, upon which sits the master copy of a book entitled Bunyah. He hands me this book. “Someone’s gotta be the first to read it,” he says. “Might as well be you. I only finished it yesterday, just before you came.”

He’s made the master copy out of a pot of glue and a pair of scissors, cutting and pasting typed poems, some old, some new, into a 150-year history of Bunyah and his place in it. It canvasses every last little anecdote he has told me in the past two days: the rotting tree that killed his uncle Archie and severed the bond between his guilt-stricken father and grandfather; the milk lorries of his youth; the dairy industry that died, his mum, the babies she never had; his burden, his Valerie, his home.

Home is the first

and final poem

and every poem between

has this mum home seam.

Home’s the weakest enemy

as iron steams starch –

but to war against home

is the longest march.

He watches me read, kneeling by his desk.

A long silence.

“Renée,” he says. “Zellweger.”

He smiles.

Old age is eating my intelligence. I can feel it already. My brain is starting to crumble. Mainly my memory.”Time, he says, is like Boris the cat. Time devours its prey brain-first. “Old age is eating my intelligence,” he says, sorrowfully.

“I can feel it already. My brain is starting to crumble. Mainly my memory.”

He must process all of his memory photographs before they disappear. Set them in ink, set them free. The thing that has plagued him for six decades, his memory, is the thing he now fears losing. But that actress’s sweet-sounding name – Renée Zellweger – is still in there somewhere and that still means something.

“What about the future?” I ask.

He shrugs. He leans across his desk, hands me another master copy of another book of poetry he’s been writing. It’s a book five years in the making, what will be his first fully original book of poems since 2010, many of them startling, confessional and brilliant. It’s called Waiting for the Past.

“What you’re hoping for in the future is what you’ve already seen in the past,” he says.

Hmmmmfff.

To get to the shop in the neighbouring town of Nabiac we drive through the gravel back roads of Bunyah in a dust-covered Volkswagen Golf. Les doesn’t wear his seatbelt and the car’s seatbelt warning system beeps politely and uselessly at him along the journey. Ding, ding, ding. We pass the Bunyah Dance Hall. Ding, ding, ding.

Les is oblivious to the now penetrating and relentless warning sound, talks over it, telling his vivid history of these brown and yellow hills.

We pass a Nabiac thrift shop that was once the medical centre where Miriam gave birth to Les 76 years ago. Ding, ding, ding.

In the Nabiac grocery store, Les Murray recites this list: “Milk, butter, bread. Milk, butter, bread.”

The car’s maddening seatbelt warning system follows us home. Ding, ding, ding. Until, inexplicably, the dinging ends. The seatbelt warning system doesn’t just stop, it quits. One of the two stubborn warring parties – Australian bush bard versus smug German electronics – had to give in and it wasn’t going to be Les Murray.

The poet bursts into the lounge room where Valerie pencils her crosswords.

“There we are Mrs Murray, milk, butter, bread!” he says, resting back triumphantly on the green sofa.

“No Equal?” Valerie says softly.

The poet slaps his forehead with his open right palm.

No equal.