A champion in and out of the ring

His remarkable personality apart, Muhammad Ali was unquestionably one of the greatest talents to grace the boxing ring.

OBITUARY: Muhammad Ali, world heavyweight boxing champion 1964-67, 1974-78 and 1978-79. Born Cassius Clay on January 17, 1942. Died June 3, 2016, aged 74.

HIS remarkable personality apart, Muhammad Ali was unquestionably one of the greatest talents ever to grace the boxing ring at any weight. In fact, the character outside the ropes, with its fluent though not necessarily logical utterances on a wide range of subjects, cornball political philosophising and muddled social and religious thinking, was sometimes in danger of supplanting in the public mind the fighting genius which functioned within them. In sheer speed of hand and foot Ali brought to the heavyweight division qualities which are seldom seen much above lightweight.

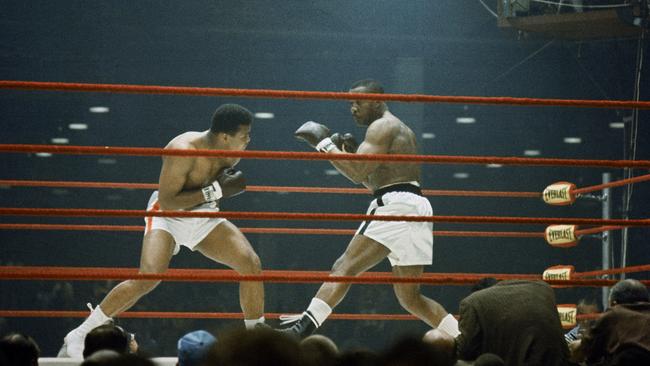

True, his unorthodox methods — the hands held low, the crossed legs, the habit of leaning back far too far — played their part in bemusing a string of opponents. But they would have counted for nothing without his phenomenal speed about the ring and an ability to land streams of punches with an accuracy which dismantled the will to resist. He also had a quality that was not appreciated until quite late in his career: bravery. No one who saw him pull himself off the floor at Madison Square Garden in March 1971 to see out a brutal fifteenth round against a rampaging Joe Frazier will ever forget the sight.

The verdict must be that no one of his great predecessors: Johnson, Dempsey, Louis, Marciano, nor formidable successors like Holmes or Tyson could have lived with Ali at his peak. His reign, punctuated by a vital four years during which — at what would have been the peak of his physical powers — he was stripped of his title for refusing to be drafted into the US Army, was a remarkably long one. And there was no tinct of “Bum of the Month” about it, as there had been in Louis’s case.

The era was rich in heavyweight talent. In 1964 the barely 22-year-old Cassius Clay (as Ali, a later convert to Islam, then was) took the title away from Sonny Liston, then hailed as one of the most awesome fighting machines ever to have stepped through the ropes. When Ali returned to the ring, after his enforced absence, seven years later, it was to encounter a new and fearsome generation of heavyweights, in Joe Frazier and George Foreman, whose punishing ministrations many younger, fitter men than he ardently wished to avoid. He eventually beat them both. Only towards the end, verging on forty, with his pugilistic powers eroded beyond all recognition, was the world compelled to watch the shadow of the athlete Ali had been, humbled by lesser men, and dismissed from the arena he had graced for so long.

In Ali’s case the fighting achievement appeared inseparable from an unorthodox brand of showmanship which made him one of the most famous personalities in the world and an inspiration to young black people in all continents. In African countries, in particular, where dictatorial governments, grinding poverty, disease and starvation were the ineluctable lot of millions of ordinary people, he became a shining example of what blacks might achieve through their own prowess. And in his progress round the continent he became a kind of ambassador extraordinary for democratic America and what it had done to liberate the energies of its former slave population.

“[Boxing was] the fastest way for a black man to make it in this country,” Ali said.At the outset of his boxing career he had the wit to see that a boastful, vaunting approach to his opponents would pack halls with fight fans just praying to see him beaten. A knack of extempore rhyming doggerel: “They all must fall/In the round I call”, in which he aimed to predict the end of his fights, only inflamed the hostility of audiences.

This all changed, especially outside America, when he became the most celebrated Vietnam War draft dodger. Ali showed himself to be a highly adept television performer and a character of boyish charm. In Britain, which had at first been outraged by his abusive dismissal of its national champion Henry Cooper as a “bum and a cripple”, he became a particular favourite. If not capable of long bursts of sustained thought, he could come out with unusual aperçus, which often darted from his brain cloaked in colourful imagery.

Muhammad Ali was born Cassius Marcellus Clay. His father had the same name which the son was later to reject as indicating his slave forebears. Cassius Clay Junior did not shine at school and later claimed that he had taken up boxing as “the fastest way for a black man to make it in this country”, though, in truth, his upbringing was no ghetto affair. His father was a successful Louisville sign painter who owned his own house from an early age.

Cassius Clay Jnr’s talent for showmanship appears to have been developed at an early age. At school he often started a fight in the schoolyard at break time just to be noticed. The pugilistic talent was more purposefully channelled when, at the age of 12, he started going to Joe Martin’s gym. He won his first amateur fight and was soon fighting on local television where Martin had a weekly show called Champions of Tomorrow. Even at that age he used to canvas support from his neighbours by knocking on their doors and telling them he was going to “whip somebody on the tube” that night.

At 16 he won the Louisville Golden Gloves light heavyweight title. A year later, still at high school, he won the national amateur light heavyweight championship. Martin looked after Clay and advised him not to turn professional too early and embark on the long, tough slug up through the clubs. He had the 1960 Rome Olympics in his sights for his young protaacgaac. A win there would automatically confer a No 10 pro rating on him.

Clay did not disappoint. Meeting the vastly more experienced Pole Zbigniew “Ziggy” Piertrzkowski in the final (since Soviet bloc countries had no pros their “amateurs” always had a great advantage), Clay eventually rendered him defenceless by the end of the last round. Elated, Clay paraded his gold medal all around the Olympic village telling everyone what was to be his constant refrain over the next few years: “I am the Greatest!”

Back at home in Louisville, he turned professional and in October 1960 won an uninspiring first pro fight against a white boxer called Tunney Hunsaker. This relatively lacklustre performance persuaded Bill Faversham, head of the Louisville syndicate which sponsored Clay, to introduce him to the trainer Angelo Dundee, thus beginning a partnership which was to take Clay to the world title. His next few contests saw a vast improvement with five opponents succumbing inside the distance.

Then, when Dundee took Clay back to his home town to face the experienced Lamar Clark in 1961, Clay made the first of the predictions which were to become his hallmark, telling the press that he would knock his opponent out in two. After felling Clark three times and breaking his nose Clay did just that. The local press were mesmerised by such prescience and Clay chose to play the mystification for all he was worth. It was the beginning of a profitable gimmick which Dundee chose not to oppose, even when it irked him.

I am the Greatest!” became his constant refrain.Soon Clay’s phenomenal reflexes and awesome hand speed were propelling him towards the ranks of true contenders. The cagey old world light-heavyweight champion Archie Moore, one of the best-loved figures in the ring, was his first real test. There was colossal publicity before the fight, with Clay intoning: “When ya come to the fight don’t block aisle or door/’Cause ya all going home after round four”. He was as good as his word. By that round Moore, overwhelmed by Clay’s combinations, was incapable of further resistance and the referee stepped in to end the fight — and one of the ring’s most distinguished careers.

By this time the case for Clay’s taking on the fearsome world champion Sonny Liston was becoming irresistible. Many reporters wanted to see it happen, just to see the “Louisville Lip” thoroughly buttoned, as all were convinced would happen. But Dundee knew he had to keep his fighter busy while the campaign for a title fight went on. This had its risks. In New York against the durable Doug Jones, Clay’s four round KO prediction went spectacularly awry and he only just scraped a points decision after 10 tough rounds.

Dundee now decided to take his man to Europe. Henry Cooper, the ageing, slow, but nevertheless well-loved British champion with a face that cut if subjected to much fistic scrutiny, seemed the perfect match. By insulting Cooper and describing Buckingham Palace as “a swell pad” Clay made a great impact in London. The crowd were dying to see their modest national hero beat the boastful young American.

In one of those moments which, like the Dempsey-Tunny “long count”, has become a part of boxing lore, they nearly had their desire. Toying with his already badly-cut opponent in the fourth, in an apparent wish to make the fight last the five rounds he had predicted, Clay took his eye off Cooper. In a flash Henry had landed his famous hammer of a left hook on Clay’s jaw and down the American went, glassy-eyed. The London crowd leapt to its feet. But the bell saved Clay and Dundee had a ploy for prolonging the minute interval. Tearing some of the padding from one of Clay’s gloves, he demanded a new pair. With the interval thus extended by another precious minute, Clay’s head cleared and he sailed out for the fifth determined on terminal execution. Within another minute Cooper’s face was a mask of blood and with the ringside crowd screaming: “Stop it! Stop it!” the referee moved in to put an end to the Briton’s torment. At ringside, Liston’s adviser, Jack Nilon, told Clay he could meet his man for the world title.

Scarcely any boxing authority in America gave Clay the slightest chance of defeating Liston in Las Vegas on July 22, 1963. Many seriously feared for his safety. Liston had just beaten the previous world champion, Floyd Patterson, for the second time inside the first round. At the weigh-in Clay gave the impression that he was in hysterical fear of his opponent. He screamed incoherent abuse at Liston and his eyes bugged. His pulse jumped from its normal 54 to 120. He went into the ring as 7-1 underdog.

But, as round succeeded round, the ringside crowd witnessed a transformation as the challenger worked Liston over as no fighter had ever done before. Completely unable to reach Clay with his heavy bombs the champion became more discouraged and his face reddened with his own blood as Clay’s punches inflicted deep cuts on it. When the bell rang for the seventh Liston stayed on his stool. He had injured a tendon in his shoulder during his futile swings at the air. Clay was the new champion. As one newsman remarked: “They sent a boy to do a man’s job — and he did it”.

They sent a boy to do a man’s job — and he did it,” a reporter said of Ali’s defeat of Liston.Shortly afterwards Clay announced that he had become a convert to Islam and a member of the Black Muslims. Henceforth he was Muhammad Ali. This did not endear him to the white members of the boxing establishment and even Joe Louis deplored the change. His father virtually disowned him. The recently-deposed heavyweight champion, Floyd Patterson even went so far as to send him a written challenge.

In the meantime the important matter of a return between Ali and Liston was to take place in Atlanta, Georgia, on May 25, 1965. This time Ali dispatched him inside two minutes with a short right-hand punch Liston never even saw. He now began a string of defences against the best heavyweights of the day. Floyd Patterson was his next victim, saved by the referee after 12 rounds of nonstop battery. In London, Cooper, whom the crowd hoped to see repeat his previous knockdown, was again rescued by the referee, this time in the sixth, his face a bloody mask.

George Chuvalo, the German Karl Mildenburger and Cleveland Williams — the latter stopped in three rounds of sheer fistic virtuosity from Ali — were among the champion’s next victims. When the World Boxing Association (WBA) put up Ernie Terrell as its rival world champion, Ali tormented him over 15 rounds to take a unanimous points decision.

Then, on April 28, 1967, after another successful defence against Zora Folley the previous month, Ali was stripped of his world title by both the WBA and the New York State Athletic Commission. He had previously refused to be drafted into the US Army and to fight in Vietnam. Convicted of evading the draft, he was sentenced to five years in prison. The next three years turned into a battle to get this overturned, a fight he eventually won in 1971.

Yet this period of enforced absence from the ring made him, if anything, more popular than he had been in his years as champion. He became one of the symbols of opposition to a war which was becoming increasingly unpopular with the American public and world opinion; but he also became a focus of interest for blacks everywhere, not merely in the US but all over Africa where he came to be held almost in reverence as a man who identified himself with the aspirations of freedom movements and demonstrated that for the black man nothing was impossible. To children and young people in particular, he was a great draw.

Ali had already returned to the ring before his successful appeal against the draft. In October 1970 in Atlanta, Georgia, as a first step on the comeback trail for a world title fight with Joe Frazier, he stopped the tough Irish-American, Jerry Quarry in three rounds on a cut eye. But the eye was Quarry’s bad luck. Ali’s ring rustiness was evident to all. The fabled speed of foot was simply no longer there. Even his celebrated timing had seemed to falter when Quarry began counterpunching.

Ali’s next test, in December 1970, before tackling the new world champion, Joe Frazier, was an even sterner one, against the Argentine Oscar Bonavena. The Argentine had twice gone the distance with Frazier, even flooring him twice on their first encounter. He had never been knocked down.

Towards the end of 15 bruising rounds with the fight so desperately close that ringside experts could not separate the pair on points and with Bonavena pressing hard, Ali suddenly struck. A left hook which the Argentinian never saw put him down for the first time in his career. Staggering to his feet at the count of eight he was almost immediately put down again. A third trip to the canvas and it was all over — a technical knockout under the rules for the bout.

By this time Ali’s performances were beginning to engender a certain solicitude in his admirers. Notwithstanding that he had pulled his irons out of the fire on this occasion he clearly needed much more time before facing a man like Frazier. But he would not take it. Frazier, his nemesis, was waiting and on March 8, 1971, at New York’s Madison Square Garden Ali went out to meet him.

Sheer hubris lost him the fight, though such a verdict takes nothing away from Frazier who applied relentless pressure for 15 rounds. But for round after round Ali lay on the ropes allowing the champion to hit him with ferocious body punches, almost, it seemed, defying Frazier to put him down. The cumulative damage to Ali’s system was simply too great. By the time Ali decided to stop fooling around with Frazier his legs would no longer obey him. It became clear, too, that he had seriously underestimated Frazier’s ability to cut off the ring and shape the fight.

By round 15 Frazier was in full cry. If there had been any doubt that it was his fight a wicked left hook to Ali’s jaw settled the issue. Ali went flat on his back with his feet in the air. He was up at three to carry on the battle, but, in truth, survival was the summit of his ambitions by that stage. That he finished the fight on his feet once Frazier had floored him is a tribute to the courage which complemented his skill.

By a strange paradox the fight may almost be seen as the pinnacle of his career. It had been replete with that drama which is always present inside the ropes when the fighter takes on the boxer. It had echoes of Dempsey versus Carpentier. In Britain (unlike America where losers are — losers) there was almost a sense of grief among fight fans. An era seemed to have ended.

In fact Ali was to go on and beat Frazier in both their next two meetings, the first a non-title affair, since Frazier had by then lost the crown to George Foreman. Then, in 1974, Ali met Foreman for his world title in a fight styled “The Rumble in the Jungle” held in Kinshasa, Zaire.

This fight was keenly anticipated, with the odds stacked heavily against Ali. In terms of sheer menace to physical wellbeing it was almost Ali-Liston all over again, this time the menace reposing in the younger man. Though it gave immense satisfaction to those who wanted Ali to be champion again, the fight nevertheless was not really of the highest class. Ali employed clever tactics, using the ring to let Foreman punch himself out, before seizing his opportunity to go on the counter attack, landing a series of stinging blows in the eighth before connecting with a big, round-arm right which ended the fight. But none of the true genius of the Ali of old was in evidence. In the interim Ali had struggled hard twice to beat Ken Norton, a tough opponent but one who would not long have detained him in his prime.

Ali defended his title ten more times, including a third, thrilling, closely fought contest against Frazier in Manila (Frazier consistently gave him more trouble than any other opponent). But there was always a sense of fending off the inevitable about this latter phase of his career. And when he eventually lost his title to the young but mediocre Leon Spinks in February 1978, many wished he would retire. Alimony payments kept him in the ring. He easily beat Spinks in the return a few months later to take the world heavyweight title for a record-breaking third time. But it was an empty statistic. His victories were now quite clearly being achieved at an unacceptable cost in physical punishment to himself.

Had Ali quit the ring for good when he “retired” in June 1979 it would probably have been too late. But he returned yet again to take on the new heavyweight champion Larry Holmes (1980) and then the Canadian Trevor Berbick (1981). He lost both fights, the defeat by Holmes being a particularly cruel humiliation as the new champion visibly did not want to inflict too much punishment on his illustrious, but now impotent challenger.

Ali had never before needed such compassion. After the Berbick fight he finally retired but Parkinson’s disease, diagnosed in 1984, gradually reduced him to a slow-moving, shambling hulk, incapable of eating without help or articulating clearly. Nevertheless, his immense popularity throughout the world ensured that he still had a useful role to play in life. With his fourth wife, Yolanda, he continued to travel, visiting Third World countries, lending his name to hunger relief and supporting educational projects, his mere presence giving hope to the poor.

When wheeled out as a distinguished guest at world championship bouts and other events, he could do little more than give a feeble smile, as he entered the public arena, supported by handlers. The smile, a mere echo of the infectious, boyish grin of his earlier years, was a sad commentary on the toll his uncompromising trade had taken on the physique and spirit of this great athlete and immensely likeable man.

Ali received the Presidential Medal of Freedom at a White House ceremony in November 2005.

Muhammad Ali was four times married: firstly in 1964 to Sonji Roi (dissolved 1966); secondly in 1967 to Belinda Boyd (dissolved 1977); thirdly in 1977 to Veronica Porsche (dissolved 1986) and fourthly in 1986 to Yolanda Williams. He is survived by his fourth wife, by their son, and by a son and three daughters of his second marriage and by four daughters of his third.