Archibald prize: larger than life

Some Archibald entrants are too big and ugly, but by and large the standard seems to have improved

THERE is some speculation, as the Archibald season gets under way, that last year's win by a very small painting would prove to have been an anomaly and the usual garage-door monstrosities will dominate the exhibition this time, as they have in recent times.

Spies were posted near the Art Gallery of NSW and very large canvases were photographed as they were unloaded and carried inside.

But not everything that goes through the door ends up on the wall; most of the paintings are rapidly consigned to an adjacent room, leaning against walls in their hundreds, after being eliminated by the gallery trustees.

In any case, whether because the general standard has improved or because the selection has been more competent than usual, this is the first Archibald for some time that one can walk through without wincing at every turn.

Last year's credible winner - a portrait of comedian Tim Minchin by Sam Leach - was of course an exception, even if it is far preferable to err on the side of too small than too big.

The natural scale for a portrait is life-size, although half to three-quarters is also acceptable. What is striking is how many reasonable pictures there are in the half to full-size range and even, at a pinch, one-and-a-half times; more than this becomes overemphatic. Of course, there are still plenty of hacks addicted to big heads.

Among the most appealing are several small pieces grouped close together, including a fine self-portrait by Lewis Miller, painted on copper, an unusual material sometimes used for precious pictures made for collectors in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Next to it is another little picture of Richard Morecroft by Peter Wegner; the comparison is interesting, for Miller tends to exaggerate colour and tone, but the result is that his image is legible from a distance, while Wegner's, though sensitive, is somewhat underarticulated in these respects.

Nearby is a good self-portrait by Pam Tippett, carefully considered and worked from life in a sober palette. Next to it is a portrait by Marcus Callum, also thoughtfully composed and executed but which has tell-tale signs of reliance on photographs: the rather flaccid sense of form, the lack of a sculptural feeling for the features and a soft-focus intended to mitigate the hardness of the source.

Next to these is a picture of Roy Ananda by Deidre But-Husaim, twice life-size and even more obviously, with its horrible air-brushed texture, indebted to photography. Why would you bother?

The smallest picture in the exhibition is what one assumes must be a self-portrait by Natasha Bieniek, very finely painted but obviously from a photo. A glance at her website confirms that she is a young artist with some ability, but that she appears to have locked herself into a very narrow and ultimately sterile dependency on the camera.

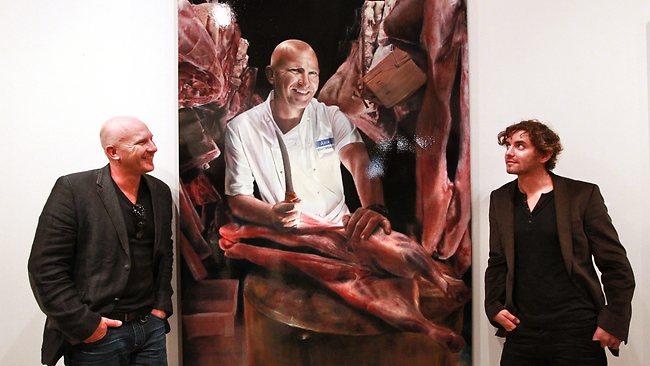

The central room is dominated by what is perhaps the most successful picture of all, a three-quarter length portrait of David Walsh, the founder of the Museum of Old and New Art in Hobart, by Geoffrey Dyer.

Although truncated at the knees, the portrait works partly because of the compositional placement of the sides of beef above Walsh, which allude to an installation in his collection and at to his obsession with death and decay. The figure is only slightly more than life-size and, unlike so many other portraits, this one embodies a living and animated encounter with its sitter.

Next to it is one of the other most plausible candidates: Nicholas Harding's picture of Hugo Weaving. It would be a better composition if the figure were smaller and more of the interior were visible; as it is, the setting remains somewhat ambiguous. But Harding captures a lively feeling of his sitter's energy, even as the actor stares away into the distance.

In the next room is the third outstanding work, a complex and allusive self-portrait by Jiawei Shen, which forms the background of Greg Weight's portrait of the artist and his family currently in the National Photographic Portrait Prize in Canberra. In the top right-hand corner of the composition a colleague of mine seems to make a cameo appearance, slightly disguised as a turn-of-the-century Chinese merchant.

It should be clear to artists and viewers alike that the main problem with this exhibition is, again and again, in the reliance of artists on the camera. This is obviously the case with the big dinosaurs, which cannot be done any other way, whether finished in the chunky textural style favoured by some or the cloyingly airbrushed manner of Christopher McVinish's huge and horrible image of Robyn Nevin. Thomas Macbeth's picture of Jessica Watson is even more patently photographic, as well as grotesquely big, but what is really interesting is the perspectival inaccuracy of the features.

The far side of the girl's face does not turn away from us to a degree consistent with the three-quarter angle of her head. This is an elementary mistake that comes from poor draughtsmanship and reliance on source material that does not provide enough three-dimensional information.

Oddly enough, an artist who may appear to be at the opposite extreme of painterliness from such photo-based realism, Ben Quilty, is guilty of related faults. His enormous head of that veteran Archibald sitter, Margaret Olley, is made up of patches of thick impasto applied over an unpainted primed canvas, so that there is no continuous paint surface. From a distance, the effect is strikingly naturalistic, but it is quite apparent that this gimmick can only work because it is based on a photo.

The problem is not confined to oversized pictures. Alexander Mackenzie's portrait of Richard Roxburgh on a bicycle is painted in the slick and yet perfunctory style characteristic of this artist. The figure looks cut out and superimposed on a background that is nothing like a sky; and the anatomical inaccuracy of Roxburgh's left leg betrays its source: photographs are deceptive in the illusion of realism they promise, poor in the kind of information a painter needs.

Of course there are countless other cases that could be pulled apart. For sheer cheek, one has to take one's hat off to Rodney Pople, who has painted on a photographic print of himself and his family in a mise-en-scene borrowed from Caravaggio's Judith and Holofernes.

But for a shameless photographic manner, we must acknowledge Vincent Fantauzzo for his portrait of Matt Moran surrounded by animal carcasses.

It may come as a surprise that both artists and sitters have to sign a declaration that the entry was painted from life. In many cases, it seems that any work from life has been a token gesture to allow both parties to sign it without lying.

Christopher Allen is The Australian's national art critic.

* * *

CONTEST'S BRUSH WITH SCANDAL

Controversy over the winners is half the fun, writes Ashleigh Wilson

FROM legal threats to challenges about artistic legitimacy and continual disputes about the quality of the winners, the Archibald Prize has courted, created and cultivated controversy for decades.

As the nation's best known and most cherished art competition, the Archibald Prize has a unique way of stirring passions among the thousands of art lovers who fill the Art Gallery of NSW each year.

First awarded in 1921, the award is judged by the gallery's board of trustees who, in turn are guided by the following criteria: "Best portrait painting preferentially of some man or woman distinguished in art, letters, science or politics."

Who would have thought 16 otherwise unremarkable words could create so many problems?

The 2004 winner, Craig Ruddy, had to go to court to defend his portrait of Aboriginal actor David Gulpilil after a Sydney artist claimed it was a drawing, not a painting. Ruddy told the NSW Supreme Court that his work was "75 per cent" charcoal, and in June 2006 he won, with the court ruling that the trustees had not erred in giving him the Archibald.

Judge John Hamilton said the trustees, not the court, were best placed to determine whether artworks met the criteria of the prize. "That matter is better left to those in the art world," he said at the time.

Last year, Sam Leach became only the third artist to win both the Archibald and associated Wynne prizes in the same year. But while his portrait of Tim Minchin was considered a fair winner, his Wynne landscape was later found to have borrowed heavily from a 1660 Dutch painting. The gallery resisted pressure for the award to be revoked amid claims it did not depict Australian scenery, as required by the Wynne prize guidelines.

In 1938, Nora Heysen became the first woman to win the Archibald with Mme Elink Schuurman; the gallery had to defend itself against claims that the subject was a socialite and not a "distinguished person".

But the biggest and most notorious drama to subsume the Archibald came in 1943, when William Dobell was awarded the prize for his remarkable portrait of fellow artist Joshua Smith. Dobell spent five days in court defending the work against claims it was a caricature, not a portrait. He won the case but the victory came at great personal cost.

"The Dobell picture of Joshua Smith is characterised by startling exaggeration and distortion, clearly intended by the artist," Justice Roper said in his judgment. "His technique is too brilliant to admit any other conclusion. It bears, nevertheless, a strong degree of likeness to the subject, and is, I think undoubtedly a pictorial representation of him."

The Archibald has not been awarded on two occasions, with judges claiming the works were not up to scratch.

In 1964, then gallery director Hal Missingham announced "no submitted entry was worthy of the award" and the board of trustees had exercised their discretion not to award the prize.

It happened again in 1980, when the board, newly appointed by the state government, decided to withhold the honour.