Zachary Rolfe documentary exclusive: murder-charge NT cop reveals why he shot Kumanjayi Walker and how he tried to save his life

The Australian has the only interview with NT police officer Zachary Rolfe, who spoke with Kristin Shorten shortly after he was charged. WATCH THE VIDEO

Zachary Rolfe spoke with Kristin Shorten in 2019. These are his words.

My name is Zach Rolfe. I am a Northern Territory police officer.

I was born in Canberra and grew up here.

My mum Debbie is a lawyer and my dad Richard is a car dealer. I have two older brothers who are twins.

I finished Year 12 in 2009 and in 2010 I joined the army.

I was posted to 1RAR in Townsville. I spent five years in the infantry and was deployed to Afghanistan in 2014.

In 2016 I joined the NT Police. I’d never been to the NT before that.

Upon graduation from the police academy in December 2016 I moved straight down to Alice Springs, which had been my first preference for a posting.

From what I’d heard it was the busiest station and the most volatile environment so I’d wanted to dive into the deep end and learn my craft down there.

The move was definitely eye-opening. To be honest, for the first few weeks in Alice I would have felt more comfortable in Kabul. It was a completely different world to Canberra where I’d grown up.

But I quickly adjusted and I loved the work. I still love it. I loved the station and working with the boys and girls on the ground.

My short-term goal was to master general policing down there before eventually applying for the Territory Response Group up in Darwin.

I applied for TRG because I want to be in that specialist unit and do the jobs that they do. To me, that’s the pinnacle of policing.

I successfully completed TRG selection in August 2018 and was waiting for a spot to open up.

In the meantime, I was happy in Alice Springs. Policing down there is very busy.

Most of our jobs are with the Indigenous community. They’re mostly domestic violence offences, alcohol-related violence offences and property offences such as break-ins.

There’s probably a higher level of violence towards police there than in other areas. I think most police in Alice Springs have been assaulted.

Since the incident at Yuendumu, NT Police have been labelled racist, but it’s simply not true.

I personally don’t care what race anyone is. I never have and never will. Race will never affect how I police or my perception, regardless of how many jobs we attend. I care about people’s behaviour, not their race.

Also, I honestly have not witnessed racism among my colleagues during my time policing.

I’ve had a number of complaints against me about use of force. They have all been investigated and, in all cases, I’ve been cleared.

Those incidents all required force to be used. That force was never excessive – it was relative to the situation on the day.

I’m a member of the Immediate Response Team (IRT) which is a semi-tactical group in Alice Springs used for high-risk jobs and high-priority arrest targets.

It depends on the job and how long we expect to be away but generally we deploy as a minimum team of four.

On Saturday November 9 I was rostered for an evening shift starting at 3pm and ending at 1am.

At 2.30pm I was just about to leave my house to go into work when I got a call from the sergeant saying that I was being sent, as a member of the IRT, to Yuendumu to arrest Arnold Walker.

Walker was a high priority arrest target because of his propensity for violence.

Information on the ground indicated that when he was at Yuendumu, he was the most prolific “breaker” in the community.

We were aware that since being released from prison in October Walker had breached his parole by cutting off his Electronic Monitoring Device and that he had returned to Yuendumu.

We were also aware that on Wednesday November 6, a few days prior to the IRT being deployed, he had assaulted two local police with an axe during an attempted arrest.

The officers involved are extremely lucky because they both could have been seriously injured or killed that day.

Immediately after that November 6 incident, the Remote Sergeant at Yuendumu started negotiating with the family of Walker’s partner for them to bring him into the local police station to be peacefully taken into custody.

The family had stated that they would comply but three days after the axe incident they still hadn’t surrendered him.

Walker was a fit, strong young man and the Yuendumu police realised they needed a higher response in order to arrest him, so on Saturday November 9 the Sergeant requested the IRT attend.

We were going to arrest him – not just for the breach of parole as has been reported – but also for assaulting police with an axe and then damaging their vehicle.

On November 9, we were briefed on the general details at the police station in Alice Springs but we didn’t have much intelligence or know where he was, so the plan was to get to Yuendumu and gather further information there.

I’d never been to Yuendumu before November 9.

Two of the IRT members were senior police officers. Myself and another member had military experience. We also went out there with a K9 handler and his German Shepherd.

We travelled in three vehicles.

The dog handler left before us and started performing active patrols upon arrival in Yuendumu.

Soon after, myself and the other three IRT members left Alice Springs in two vehicles.

We arrived at the Yuendumu police station at about 6.30pm and had a quick intel briefing there with the Remote Sergeant, Julie Frost.

I got maps of the area and we left the Yuendumu police station just before 7pm.

It was coming to dusk. There was ambient light outside but inside houses it was getting dark.

Each of us had Tasers, Glocks, pepper spray and batons. One of the boys was carrying a beanbag shotgun and another was carrying a rifle.

The other boys were wearing their police-issued load bearing vests with armour inside.

I was wearing covert body armour under my general duties police shirt. That’s just my preference as it’s a bit lighter and I can move better in it.

We all had body-worn cameras on and as soon as we stepped out of the cars, those cameras were rolling.

First, we attended the house where the axe incident had occurred on November 6 and a man there informed us that Walker was at another group of houses approximately 600m away.

Unfortunately, because we only had the light information that it could have been any one of the three houses, we couldn’t put in a proper cordon.

So, two of the IRT guys and the K9 handler acted as spotters on the external sides of the houses in case Walker ran.

Myself and another officer just started talking to the people in the yard, asking them for information and whether they’d seen Walker or his ‘wife’ Rickisha.

Everyone who we spoke to, who turned out to be his family, told us that they had not seen him, didn’t know where he was and that he definitely was not inside the house where we found him.

Myself and my partner walked into the middle house – the red house – and immediately bumped into a man matching Walker’s description on his way towards the front door.

He approached us and tried to walk past us. We asked him his name and he told us it was Vernon Dickson.

At that point, the man’s hands were empty which is why I got so close to him.

I asked him just to stand next to the wall while I put my phone next to his face to compare him to the mugshot I had saved.

The mugshots aren’t ideal but I could see that it was Walker and slipped my phone back into my pocket.

I tried to keep him calm, told him that everything was fine and asked him to put his hands behind his back.

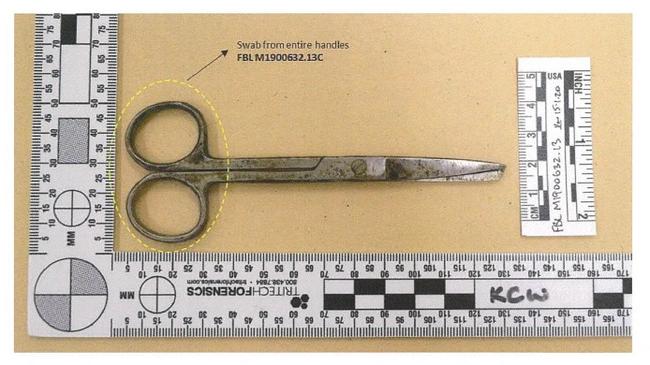

He then reached into his pocket and grabbed the scissors.

At that point, as fast as it can, the interaction escalated from nothing to 100 per cent.

Walker hit me twice in the head and I could tell from boxing experience that he was hitting me wrong. He wasn’t using his fists and his hand was angled a bit differently.

Then I looked at his right fist and saw a metal blade before I felt it penetrate my shoulder which I was using to protect my neck.

I didn’t immediately identify the weapon as a pair of scissors but that doesn’t change what I would’ve done. You can still kill someone extremely easily with a pair of metal scissors.

I then hit Walker, giving him a quick jab and stepping back to create distance.

My partner hadn’t observed the blade and stepped in, going hands-on with Walker, to effect the arrest.

At this point, I observed Walker strike my partner in the chest and neck area with the blade multiple times.

I pulled out my Glock and fired one round into the back of Walker’s torso, to no effect.

I completely understand why people without the knowledge would ask why I didn’t go for my taser but the taser is an ineffective tool when you’re in such close proximity. You can’t trust the taser to work where there’s the threat of death.

Capsicum spray is good to avoid a fight that hasn’t happened yet or split up a posturing fight but it wouldn’t have stopped the struggle. It would have just stung and potentially blinded all of us in the room.

The non-lethal accoutrements I had on me at the time would have been ineffective in that close-quarter situation where there was the risk of serious harm or death.

And I was in immediate fear that any one of those blade strikes could have caused serious harm or death to my partner.

As per our training at the police academy an edged weapon is a lethal weapon and the response is to use your Glock if required. I just followed my training.

I had never shot anyone before that encounter.

As soon as the first shot was fired, I could hear screaming and wailing outside.

My partner and Walker stumbled and fell onto a mattress on the ground.

The first round did nothing to neutralise the threat.

I saw Walker continue to strike multiple times at my partner’s neck area, so I fired two more rounds into Walker.

It wasn’t until after the third round that he stopped trying to stab my partner.

That was the minimum force that was effective in stopping that threat to life.

Obviously, it was difficult in that environment and in that close quarter scuffle, but if I wasn’t confident that I could take those shots without putting my partner at risk I wouldn’t have.

After the third shot I holstered my Glock and pushed my partner off him, out of the way, and rolled Walker on to his stomach.

I saw that he had a pair of metal surgical scissors in his right hand.

I ordered him to let go of the scissors and when he refused, I tried to pull them out of his hand.

I repeatedly demanded he let go of the scissors but he wouldn’t and continued fighting us. He also stated that he was going to kill us.

My partner eventually pried the scissors from his fingers and flung them on the floor.

Walker was still trying to fight us so we handcuffed him and I was about to glove up to provide first aid when another IRT member at the door informed us that we had to leave as there was now a threat to our safety.

He had observed community members flocking to the house and perceived them to be violent and aggressive.

We picked Walker up by his armpits and quickly carried him outside to the police vehicle.

My partner and I lifted him into the cage on the back before climbing in to render first aid on the way to the police station.

It was about a two-minute drive and at that time he still had a lot of fight in him, so we searched him for weapons before removing his handcuffs and assessing his injuries.

There were no medical staff at the clinic. They had been evacuated from Yuendumu earlier that day due to fears for their safety. So, we drove to the police station and got Walker out.

We stripped him down to his underwear to better assess his injuries before moving him into the police station for treatment.

We laid him down in a cell in the watch house side of the police station because it’s the cleanest part of the police station and close to the first aid equipment.

Myself and the other IRT member with military experience had the most medical experience so together we took charge of the first aid and did what we could with the resources that we had.

Walker would have been suffering from a mix between a pneumothorax and a hemothorax, which is where the air is released from a penetrated lung into the chest cavity.

We sealed the wounds as best we could with a three-sided bandage to allow the air to escape his lungs without increasing pressure in his chest cavity.

There was not much more we could do with the kit that we had except to maintain observations on him and get the defibrillator ready in case his heart stopped.

Walker had sustained priority one injuries which meant that he needed to reach a surgical ward within an hour for any chance of survival.

For the first 70 minutes, Walker was still moving, talking to us and holding our hands.

We were just trying to make him comfortable and reassure him, despite our concerns.

He was just saying that he felt funny which was normal as he started going into shock.

For 70 minutes he was still with us and talking to us, so we kept him alive past the golden hour but unfortunately, due to the lack of medical resources available, we could not keep him alive beyond that.

The Sergeant had been attempting to get other medical resources to our location but it was too dangerous for RFDS to land their plane because the community was nearly rioting at this point.

The two nurses who did manage to reach our location that night from Yuelamu – these nice ladies in their 60s and 70s – were assaulted by the community.

Rocks were thrown at their ambulance and one of the nurses was hit on the head.

Meanwhile Walker wasn’t in pain, he was just getting tired, and then quietly passed away.

We conducted CPR for another half an hour after that but there were no signs of life.

At that point we had to start worrying about security.

From inside, we could hear the community throwing rocks at the police station.

There was communication between the police and the community outside but the decision was made not to immediately inform the community that night that Walker had died for security reasons.

We felt that the threat to police and medical staff – due to how it looked like the community would react – was too high.

There was a plan to evacuate the police station. We had loaded all of our kit into vehicles and we were ready to go but as we were about to step off an assistant commissioner in Alice Springs directed us to return to the station as reinforcements would be sent to us.

Six police officers then flew out from Alice Springs on a small police air wing plane.

They had to circle above Yuendumu until it was safe to land because there were community members on the air strip.

At about 11pm, we did a quick convoy out to the plane. The extra police members got off the plane and I hopped on.

I returned to Alice Springs because I needed medical treatment for my stab wound and for the purposes of the investigation.

I landed in Alice Springs just before midnight and went to the hospital where my wound was cleaned and patched up. After I was treated and given a tetanus shot – and detectives seized my clothes – I returned to the police station where I spoke with the lead investigator of the incident at that time.

He had already watched the body-worn video (BWV) and informed me that my actions had been cleared through justification. They were now just following up on authorisation which was the administrative side involving questions like whether I was wearing the correct police uniform and had power of entry.

The lead investigator informed me that he’d be in touch with me later that day because it was now Sunday morning, to get my statement, and I returned home at about 3am.

I got a few hours’ sleep before returning to the police station on Sunday where I met with the police psychologist who cleared me to return to work.

By then the Northern Territory Police Association had put me in touch with lawyers who advised me to decline a police interview at that time.

I was rostered for two days off and had planned to return to work as normal on Wednesday.

Initially I didn’t believe there would be any ramifications from the incident. It was a clean shoot.

There was footage of it from both myself and my partner’s body-worn camera.

Tuesday morning, I woke up with a number of the NTPA members knocking on my door to inform me that my name had been released on social media.

I did expect, because Alice Springs is such a small community and a number of hospital staff were aware of what had happened, that my name would be released. I just didn’t expect it to happen so soon.

I started receiving threats through social media. We were taking them seriously. There were definitely legitimate concerns for my safety that day.

NT Police assistant commissioner Narelle Beer then asked me to go to Darwin but I declined.

Meanwhile, my mum was on her way to Alice Springs. As a result of the incident, she had organised to come up for two nights to catch up and check that I was OK.

After she landed, we decided that I should take a few weeks’ leave and get out of town. At this point I was in no trouble that I was aware of.

Then on Tuesday afternoon AC Beer said that it was now a direction that I travel to Darwin, which is an order that I have to obey or disciplinary issues would follow.

So, on Tuesday afternoon mum and I flew to Darwin and stayed at the police visiting officers’ quarters (VOQ’s).

On Wednesday in Darwin the police brass kept stalling about a decision on where I was to go from there so at about 3.30pm I called my police liaison – a superintendent in Darwin – and informed him that I’d be on a flight the following morning, Thursday morning, to Canberra.

An hour later five detectives rocked up to the VOQ and placed me under arrest for murder.

They transported me to the Darwin watch house where they processed me and put me in the cell for about five hours before charging me with murder.

After that there was an out-of-session court hearing for a bail consideration with the on-call judge.

The detectives read out – to the judge over the phone – the statement of facts, which was about 90 per cent correct.

Police denied me bail but informed the judge that if I was willing to follow their bail conditions, they were happy to approve bail.

The judge granted me bail if I agreed to leave the NT, reside at my parent’s house in Canberra, sign into a police station every week, relinquish my passport and have no contact with the police officers who were at Yuendumu on November 9.

I feel like I was ambushed and flown to Darwin because it would have been more difficult to have me arrested in Alice Springs where the investigative team had all seen the BWV and knew what had happened.

A couple of hours after the shooting, the BWV was on the police system.

I still get mad every now and then about the treatment from the NT Police brass.

I feel like they threw me under the bus.

They had evidence that cleared me yet they still arrested me for murder.

The leadership sacrificed me to appease a crowd which is not what a good leader would do. A good leader should take the hits. If they have a win, they should give it to the team. And if the team has a loss, a good leader takes the loss.

They should have stood up and told the truth or just released the BWV if they didn’t want to defend me themselves.

I want to tell my story because the NT Police didn’t stand up in front of the media and tell the truth.

It is extremely unfortunate that Walker passed but I did what I had to do to protect my partner and myself. I had been stabbed but my main concern at the time was my partner, who has a wife and kids.

Walker put us in that situation. He put my partner’s life at risk and my own life at risk.

I would not do anything differently. I do not wish I’d done anything differently.

All I can say is that I’m not racist. I don’t care what race anyone is. All I care about is behaviour.

To put it as bluntly as I can, if a white guy stabbed me and tried to stab my partner, I’d shoot him just the same.

–

Watch our exclusive Zachary Rolfe interview and documentary — and read all our coverage — at theaustralian.com.auor the app.

Hear all the news and analysis in our daily podcast Yuendumu: The Trial, available by searching ‘Yuendumu’ wherever you get your podcasts