Fears began when he was a newborn: Kumanjayi Walker’s tragic life before he was shot by NT cop Zachary Rolfe

Abandoned as a baby, Arnold ‘Kumanjayi’ Walker survived a tragic childhood to die at the hands of police. His life story can be revealed for the first time.

Arnold Charles Walker was just a tiny baby when the alarm bells started ringing for adults seriously concerned about his welfare.

But the odds had been against him before he was even born in Alice Springs Hospital on October 13, 2000.

His birth mother, Luritja woman Selina Lane from the Central Australian Indigenous community of Haasts Bluff, was a “sniffer” who drank heavily while pregnant with the boy who, after death, would become known as Kumanjayi Walker.

Soon after his birth, Lane – for reasons unknown – gave her newborn to Leanne Oldfield and Sampson Anthony who “grew him up” in an environment of “alcohol abuse and severe domestic violence”.

Oldfield told authorities she was friends with Kumanjayi Walker’s biological parents but was not related to either of them.

By April 2001, at seven months old, he was living with Oldfield and Anthony at a town camp on the outskirts of Alice Springs but a dispute had erupted between Walker’s maternal and paternal relatives over who should care for the infant.

Both sides claimed the other was incapable due to alcohol abuse.

A couple of months later, in June 2001, community members raised concerns the couple were struggling to cope and the baby was not thriving.

By Kumanjayi Walker’s first birthday, a dispute between his grandfather and Leanne Oldfield was underway.

Kumanjayi Walker’s paternal grandfather accused Oldfield of always being drunk and claimed she didn’t dress the boy known as “Charles” appropriately for the weather. Concerns were being raised their home was “filthy”.

Kumanjayi Walker, now 15 months old, was supposed to be living with Oldfield, but it was now unclear who at Warlpiri Camp was actually caring for him.

By September 2002 Walker was being cared for by his grandmother but was described as “failing to thrive” and simultaneously suffering from an ear infection, a chest infection, nits and scabies.

As a child, he also spent stints living in Katherine with Oldfield’s aunt Meggery Brown and at Ti Tree with Margaret Brown, before she moved to Yuendumu, a town of approximately 800 residents, 300km northwest of Alice Springs.

Around 2007 the couple — Oldfield and Anthony — moved with the boy to Adelaide.

Kumanjayi Walker was enrolled at McFarlane Primary School from 2007 to 2010 where teachers identified him as having “special needs”.

In 2010 Oldfield left Adelaide, with Walker, for Yuendumu where her family – including Margaret Brown – now lived.

It was at Brown’s house, number 511, where police would fatally shoot Walker a decade later.

But it’s impossible to understand that incident without knowing Walker’s history.

Sampson Anthony followed Leanne Oldfield and Kumanjayi Walker to the NT but wound up in prison in Darwin, where he died in 2014.

After returning from South Australia, Kumanjayi Walker was enrolled at Yuendumu Primary School from May 2010 until August 2012.

He began committing break-ins when he was 11.

“It was the big kids’ idea,” he always said.

When Walker was 12, he entered the government-funded Mt Theo Program, run by Warlpiri Youth Development Aboriginal Corporation (WYDAC), which started in 1993 to address Yuendumu’s petrol sniffing epidemic.

The then-Outstation Co-ordinator of the Mt Theo Program Kerri-Anne Chilvers observed that Walker was hard to engage and considered him to be a “dysfunctional child with poor impulse control and inability to control his emotions”.

“He has poor understanding of what he does as he often acts on impulse and does not understand the consequences of his actions,” Ms Chilvers noted at the time.

She also expressed concern about his cognitive function due to his “prolonged exposure to domestic violence” while with Ms Oldfield and her suspicion that Kumanjayi Walker may have suffered frontal lobe damage as a result of his biological mother’s petrol-sniffing.

After a trip back to South Australia with Ms Oldfield, Kumanjayi Walker returned to the NT and re-enrolled at Yuendumu Primary School in October 2013 although his attendance was “extremely low”.

The principal said when Kumanjayi Walker was present, he “would not be participating” and that she too believed he had “special needs”.

“This school is not suitable for Arnold – we do not have the services/resources Arnold requires,” she said at the time.

“Arnold is growing older, his needs increasing and he is becoming more difficult to care for”.

At that time, he was living with another ‘grandmother’, Jean Brown, and her partner Allan Dixon in Yuendumu. They also cared for other children, and it became clear to adults who interacted with the family they were struggling to control him.

Ms Brown said the boy had been attending school but “stays away when kids tease him”. “They call him crazy,” she said at the time.

“He has had these problems since he was young.”

Pointing to her head, she explained that his problem was that “he gets angry”.

Jean Brown believed the boy had mental health issues resulting from his biological mother’s chronic substance abuse during pregnancy, but this was never proven.

Kumanjayi Walker liked living with Grandma Jean.

“She buys food – everything,” he said at the time.

“She treats me good and takes us to school.”

He frequently wagged school, exhausted from spending his nights walking around the community.

By age 13, he regularly drank alcohol and smoked ‘gunja’ (cannabis) daily.

He would steal spray cans from adults in Yuendumu to inhale the petrol, paint or deodorant that he was addicted to despite saying they “made him feel dizzy and hurt his brain”.

And at age 13 his behaviour escalated to a new level. He broke into buildings, damaged property and vandalised vehicles.

In April 2014 he broke into and trashed the Yuendumu Medical Clinic and the newly built early childhood learning centre, causing an estimated $130,000 of damage.

This is the same clinic from which staff would later be evacuated, due to their fear over break-ins, on the morning of Kumanjayi Walker’s fatal shooting in November 2019.

There was a further estimated $100,000 damage done to the water tower that night which Kumanjayi Walker was suspected to have been involved in.

He told others, at the time, he did the damage because he was bored and “for fun”.

The Yuendumu Night Patrol reported seeing Kumanjayi Walker wandering around the community every night.

‘Grandma’ Jean Brown said she would go looking for him at night to try to stop him from wandering around the community after dark but she also made excuses for him.

“He gets angry when other kids tease him – he goes off his head,” she said.

Around this time a female government worker who visited the family had to be hidden for her own safety when Mr Walker threatened to “smash” her with an iron bar.

On April 29, a Yuendumu community meeting took place where everyone present agreed that those who had destroyed the medical clinic and child care centre should be punished.

Kumanjayi Walker came to that meeting to identify the others involved, naming three young children aged between 7 and 11.

Kumanjayi Walker was barely a teenager, but he was effectively homeless, without a responsible adult to care for him.

The Mount Theo Outstation was reluctant to have him back, and Ms Oldfield said he should return to live with Jean and Allan in Yuendumu.

“I would like him to go hunting and do men’s things,” she said.

“Allan will take him out bush and he knows about his problem,” referring to the boy’s mental health problems.

“He can’t sit still. He would get up every five minutes. He gets angry when someone gets him upset and when he gets teased.

“Arnold would listen to Allan; sometimes when he stays with me, he gets angry”.

Another of Kumanjayi Walker’s grandmothers, Katrina Brown, who sometimes cared for him, said he didn’t listen to her either.

In mid-2014 it was agreed Kumanjayi Walker, now 13, would live with BushMob, a residential program to help marginalised young people – but he was reluctant to go, threatening the adults who tried to encourage him.

In the weeks that followed, new incidents occurred.

First he graffitied the school bus. BushMob staff – aware of his ‘like’ for graffiti – tried to turn this into a positive interest by “providing him with materials to allow him a creative outlet by pro-social means”.

Then Kumanjayi Walker took a knife from the kitchen and threatened another boy, whom he accused of teasing him.

He stole a car and assaulted a 12-year-old boy, eventually leaving the BushMob program.

At 15 — after dozens more episodes of stealing cars, damaging property and fighting with other youths — he moved in with his grandmother, Margaret Brown, at house 511 in Yuendumu.

In 2015 he met a young woman, Rickisha Robertson, and began bashing her.

He was stealing, damaging property and terrorising Ms Robertson – behaviour he blamed on his habit of sniffing deodorant.

He went to Papunya to live with his biological grandparents Phillip and Ena Lane, but rarely spent time in their home, instead returning to Yuendumu to be with Ms Robertson.

Kumanjayi Walker had little understanding of the effect his behaviour had on his victims such as when he stole the Yuendumu medical clinic car and how this prevented people in the community from getting medical treatment.

He claimed he only assaulted Rickisha Roberston once when he was smoking ‘gunja’ and said at the time he didn’t know why he did it.

He had no interest in finding a job and was happy to spend his days watching TV and smoking.

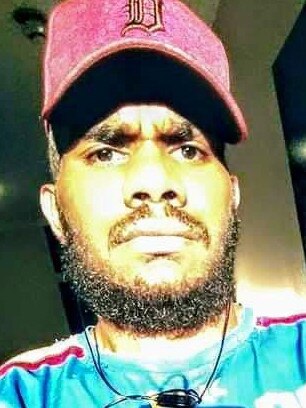

He had half a dozen different Facebook accounts where he shared photos of himself posing as a gangster and followed Mariah Carey fan pages.

He followed Collingwood and was part of the East side in the Papunya competition, but sources said he did not play. “He would just walk around and not listen to anyone,” one said.

Kumanjayi Walker confided in others he was lonely and missed his family, but Ms Oldfield refused to take him in and his great-aunt Meggery Brown, in Katherine, said she was unable to support him.

A relative in Papunya, Joseph Lane, said at the time: “He mad one, he don’t listen, he walk around day and night. He make trouble for everyone. He need to be locked up for long time.

“He chase little dog and puppy and he tease them like little kid brain do.

“He is young man. He should know more but he know nothing”.

Mr Lane said he felt Kumanjayi Walker needed “some help for his head” because “he does not listen and he does not care”.

“He does not listen, he can’t understand, I tell him but nothing”.

Papunya elder Sid Anderson said the young man caused too much trouble in the community and makes life hard for others.

“That mad one is not welcome back here,” he said.

“He breaks into shop and clinic and steals people’s cars.

“Smoking gunja and making trouble is not our way.”

Mr Anderson said Walker needed to “listen and respect our community”.

“This boy has no idea who he is,” he said.

“He does not listen to anyone, especially the old people.”

After the shooting, his Papunya relatives told the media Kumanjayi Walker was a “funny and friendly” young man who had a lot of friends.

Yuendumu police regarded him as a sniffer and the local ringleader of break-and-enters, describing him as a risk to community harmony.

Both the Yuendumu Clinic Manager and the Alice Springs Hospital said in official reports Kumanjayi Walker had no documented history of cognitive or mental health issues.

Mr Walker was open about his life: he received money from Centrelink and spent it all on food, clothes, grog and “smokes”.

By this time, his biological relatives in Papunya and Haasts Bluff, and his adoptive relatives in Yuendumu were all fed up with his behaviour – but Leanne Oldfield said she was again willing to care for him at Warlpiri Camp at Alice Springs.

But that’s not what Kumanjayi Walker wanted; he “got on the bus with the footy team and left for Yuendumu,” Ms Oldfield said soon afterwards. “He wants to see Rickisha.”

“Family in Yuendumu might have him, but he shouldn’t go there,” she said.

“He always gets in trouble when he goes there.”

Ms Oldfield lamented: “no one will keep him from Rickisha … he will listen to no-one,” she said. “Arnold will always go back to her.”

Kumanjayi Walker continued his spree of vandalism, fighting and abuse until October 2018, when he checked into a rehab facility briefly before returning to Yuendumu.

In November – now aged 18 – he appeared in court, represented by the North Australian Aboriginal Justice Agency on two counts of assault.

The lawyers applied for bail, arguing that “being on bail will lessen the likelihood of reoffending” and that he would “suffer significant hardship” should he have to remain in custody until the March hearing.

Kumanjayi Walker agreed to be admitted to rehab at the Central Australian Aboriginal Alcohol Programs Unit. “I need to go there. Too much drinking and smoking,” he said. “Drinking and smoking (cannabis) causing problems”.

He said he wanted support and that support officers should “visit me to check that I am doing okay … I want to finish CAAAPU and stay out of trouble. Be happy life, be with family.”

In early February 2019 he completed a three-month program at CAAAPU and then moved back in with Ms Oldfield at Warlpiri Camp in Alice Springs.

On March 5 support officers thanked him for complying with his bail conditions and offered to arrange for him to have a haircut “as a reward for his efforts”.

Kumanjayi Walker told the Community Youth Justice Officer (CYJO) that he wanted to attend a funeral for his “little sister” at Yuendumu on Monday 11 March.

The caseworker allowed him to go so long as he stayed with Ms Oldfield and was back at Warlpiri Camp by 7pm on Saturday, 9 March 2019.

Kumanjayi Walker’s Electronic Monitoring Device was then suspended until 7pm on Saturday, 9 March 2019.

At 7.07pm on Saturday March 9, NT Police were contacted to advise the strap had been tampered with at Yuendumu.

At 1.12am on Monday March 11 CCTV footage captured Kumanjayi Walker entering Mai Wiru Regional Stores, known as Big Shop, in Yuendumu through the ceiling with an unknown co-offender.

Kumanjayi Walker obtained keys from inside the office and used them to attempt to gain entry into the room containing the cigarette safe and cash safe.

He made two failed attempts, using two separate sets of keys, to gain entry to the safe room.

He then approached the CCTV camera and ripped it from its housing, leaving it dangling, facing towards the ground.

The CCTV monitor had been thrown on to the ground and smashed.

The cabling and wiring for the security system and CCTV camera inside the office had been ripped out.

But the cameras had already captured Mr Walker – who despite having a black bandana wrapped around his face – was wearing distinct yellow Nike shoes and red, black and yellow socks with palm trees on them.

The store manager attended the store and found that the keypad and turning mechanism had been ripped off the cash safe.

The office had been trashed with paperwork, garbage and shredded paper strewn around the room.

Walker and his co-offender had stolen up to $7000 worth of cigarettes.

On Mar 19, 2019 Yuendumu Police officer Senior Constable First Class Christopher Hand arrested Walker for breach of bail. Eight months later Walker would chase Sen Const. Hand with an axe.

On June 26, 2019 Walker was convicted of unlawful entry, damage property and stealing in the Alice Springs Local Court.

Judge Birch sentenced him to 16 months prison, backdated to February 22, 2019 and partially suspended so that after serving just half of it, Walker could attend another eight-week rehabilitation program at CAAAPU.

On October 21, a week after Walker’s 19th birthday, he was released from prison to begin his CAAAPU placement.

Conditions of his suspended sentence included that he remain at CAAAPU in Alice Springs, abide by a 7pm curfew and be subject to electronic monitoring.

A week later, just after midnight on October 29, Walker cut off his Electronic Monitoring Device and absconded from CAAAPU.

“The offender’s current breach of his conditions demonstrates a disregard for his suspended sentence and a desire to not be located by way of his EMD,” departmental notes stated.

The next day, October 30, Walker was listed as an NT Police arrest target and Yuendumu police were told to ensure that Robertson – as a domestic violence victim – knew.

An NT Police Intelligence Support Officer issued an urgent internal alert stating that Walker “represented a danger” to Robertson.

“Good Morning Everyone, Please NOTE – Arnold Walker has absconded from CAAAPU and is currently an arrest target for breach of suspended sentence. If you are currently engaged with Ms Rekeisha (sic) ROBERTSON – please ensure she is aware.”

Walker was then listed as an arrest target on daily taskings sent to Alice Springs police members.

Alice Springs police searched for, but failed to locate, Walker who was now – once again – on the run.

On Friday November 1, a Community Probation and Parole Officer (CPPO) visited Walker’s adoptive mother Oldfield at Warlpiri Camp who advised that Walker had got a lift to Yuendumu two days earlier on Wednesday Oct 30.

Oldfield told them that he might be staying with his grandmother Margret Brown or Robertson’s family on the west side of Yuendumu.

On Tuesday November 5, a warrant was issued for Walker’s arrest for breaching his suspended sentence.

Just after 5pm on Wednesday November 6 a Yuendumu community member informed Senior Constable Lanyon Smith that Walker was at house 577.

Walker’s violence, when the two officers arrived to arrest him, could have got him — or them — killed.

Walker escaped that day but his next encounter with police would be fatal: shot three times by Constable Zachary Rolfe, who was later charged with murder just four days later, as Black Lives Matter protests swept the nation. Rolfe was on Friday found not guilty of Walker’s murder.

–

Watch our exclusive Zachary Rolfe interview and documentary — and read all our coverage — at theaustralian.com.au

Hear all the news and analysis in our daily podcast Yuendumu: The Trial, available by searching ‘Yuendumu’ wherever you get your podcasts