William Tyrrell’s hunter Gary Jubelin is now the hunted

Gary Jubelin’s trial has exposed many of the secret and fascinating techniques police used in William Tyrrell’s abduction case.

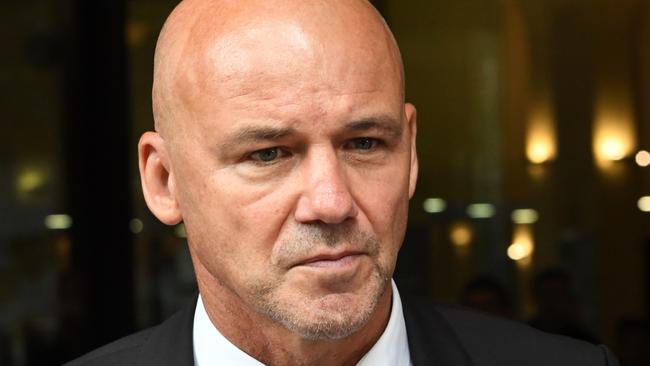

It’s the same scene every day. Gary Jubelin comes striding, maybe even bounding, up the steps of Sydney’s Downing Centre Local Court in a super-sharp, slim-fitting black suit, his bald skull gleaming like the head of a copper bullet.

His supporters, who wait on the steps, break into cheers and applause: “Go get ’em, Gary!”

These are people to whom Jubelin gave succour during his long career as one of Australia’s best-known and most successful homicide detectives. He found their loved ones. He has brought killers to justice.

Now he is on trial.

Jubelin is facing four criminal charges related to his handling of one of Australia’s longest and most perplexing investigations: the disappearance of foster child William Tyrrell more than five years ago.

The trial has exposed many of the secret and fascinating techniques that police used to try to find the person who took William. They put surveillance devices in people’s homes, and attached them to their cars.

Well, that’s obvious.

GRAPHIC: Investigating William Tyrrell’s dissapearance

They got a copy of the tiny, two-piece Spider-Man suit that William was wearing and buried it in the dirt, to make it look old. Then they left it on a popular bush trail, and hid “operatives” in the forest to record what happened when a particular “person of interest” came upon it.

They had people undercover. One posed as a clairvoyant. Another posed as a PhD student, ostensibly researching “the impact on a small village like Kendall, of a crime such as this”.

They had tiny cameras up in trees in the bush around Kendall on NSW’s mid-north coast.

Was William buried up there? If so, would somebody come and check the body, or the grave? Detectives desperately wanted to solve this case. It is one of the nation’s most harrowing. William was only three when he went missing. He was in the care of foster parents, and he was visiting his foster mum’s mother at her house on Benaroon Drive in the lovely and leafy village of Kendall, for the weekend.

He was there about 10.30am on Friday, September 12, 2014, running around the garden, roaring like a tiger … and then he was gone. Nobody saw anything. And nobody heard anything.

Police have no sighting, and no forensics.

A strikeforce was formed, and it is now plain that rival detectives near the top of the operation almost came to blows as they grappled with the trauma, and the complexity of the case. They had thousands of tips, not enough staff, hundreds of leads, and no real idea.

And one of those former detectives — he has quit the force — is now on trial.

In essence, the crown says Jubelin recorded four conversations with a person of interest, Paul Savage, without having the proper authority to do so.

It’s a baffling situation, on so many levels.

Even if it’s true — and we don’t yet know, since the case is ongoing — why it couldn’t be handled as an internal matter, without all the sensational publicity and the exposure of so much of the police work, is anyone’s guess.

Three of the relevant conversations were recorded when warrants for listening devices — and the bugs themselves — were in place, meaning police were recording conversations at Savage’s house, as well as on his mobile phone and landline.

But Jubelin allegedly used his own phone to record the calls, mainly as a back-up, and his phone was not covered by the warrant.

The court has heard that the bugs in Savage’s house tended to produce recordings of “poor to very poor” quality.

Savage listens to Ray Hadley — a nice-and-loud radio talkshow — for hours every day, and not at a low volume. He is also a lonely widower who mutters to himself and to his dead wife, Heather, pretty much constantly.

The fourth recording was made when no warrants were in place. That would seem to be more serious, except that there had been a warrant. It had simply expired. A new one was soon issued.

On the face of it, this is not a detective “gone rogue”. He wasn’t chasing down a suspect who wasn’t already under surveillance.

Savage was very definitely under surveillance. The police had cameras in the bush around his house as well.

The court has heard that he, or rather his adult daughter, found one of the cameras and kept it for several weeks.

Savage has strenuously and repeatedly denied having anything to do with William’s disappearance. He has never been charged and there is no evidence to link him to the crime.

Jubelin was, during yesterday’s hearing, in a roundabout way, given an opportunity to explain why the team investigating William’s disappearance made Savage the target of their attention.

The court was shown an interview that Jubelin gave to officers from Professional Standards, shortly before being charged with these offences.

“I’m thinking around 2017, the name Paul Savage was raised,” Jubelin said.

“Someone made a comment, after his wife died. He was walking around with an A3 picture hanging around his neck of his dead wife. It was bought to my attention that he also stole one of our covert bush cameras … I thought this was strange behaviour.

Jubelin then discovered that an AVO had been taken out against Savage, who had been accused of stalking the local “post lady” by following her after she had delivered his mail, to tell her he loved her.

He looked at some of the early statements Savage had given, after William first went missing.

“Paul Savage, we know, he’s a street stickybeak,” Jubelin told investigators. “His version of events was that he didn’t hear any of the commotion (in the street on the morning William disappeared.)

“His version of events, he went walking up into the bush, uphill, got a little bit lost, and came back and had a cup of tea.

“That makes me suspicious. It’s against his character. Someone invests so much time to look for (William) and simply goes into the house and has a cup of tea … that is strange.”

Jubelin looked at the circumstances surrounding the AVO.

“She (the post lady) had been stalked by Paul Savage,” he said.

“It got to the extent where he would come out and say I love you, turning up at the post office — crying shaking, saying we need to be together.

“He kept harassing her … police took out an AVO, he breached it, he was charged, he pleaded guilty.”

By Jubelin’s account, the “harassment” — which Savage denied to him — then stopped.

During that time, he said, Savage turned his attention to William’s foster grandmother, who lived opposite him, and had recently become widowed.

“He would turn up unannounced and just stand there and stare at her,” he said.

Two days before William disappeared, the court heard, the “post lady” was due to visit William’s foster nana on Benaroon Drive where William was staying when he went missing.

Jubelin wondered if Savage would have been “hyper-vigilant” and looking out for her.

William ran out of his foster nana’s house at around the same time Savage saw Heather off to bingo, and around the time a postie might come into the street.

Had there been an accident?

“Thinking outside the square, I came up with a plan. It was thought-out. I had a Spider-Man suit buried to make it look old,” Jubelin said.

The police left it on a bush track Savage frequented, hoping he would come across it. “He might pick the Spider-Man suit up and hide it, which would be an unusual reaction,” Jubelin said.

Savage insists that he reported the suit as soon as he found it.

Jubelin was also intrigued by information from a listening device in Savage’s car. “One of the things we captured was: I think they’re onto me, love, don’t dob on me, don’t dob on me, or words to that effect,” he said.

They can’t know who he was talking to, since he was alone in the car. Jubelin said he did have a habit of talking to his dead wife.

Savage has appeared only via video. He claimed Jubelin threatened to “bring me in, arrest me”.

The court has heard a tape of the relevant conversation, which does not capture such a threat.

“He told me how he knew I’d done it and all the rest of the rubbish and he wound up saying I’ll be back tomorrow to take you in,” Savage said. “He was telling me he was going to arrest me.”

Savage was asked by crown prosecutor Philip Hogan SC whether he remembered “a time Jubelin came to your house (on May 2, 2018) and had quite a long conversation with you?”

“Yes,” Savage replied.

“That day, did he tell you he was recording the conversation?”

“No.”

Barrister for Jubelin, Margaret Cunneen SC, suggested to Savage: “You always knew that he was one of the more senior officers involved in the disappearance of little William … you knew it was his job to investigate, that his job was to try to find out what happened to William Tyrrell.”

“Yes,” Savage replied.

“Sometimes he was very hard on you in his conversations, would that be fair?”

“He liked to be the boss, yeah.”

“Other times he was a bit more friendly?”

“Very rarely.”

“You were cranky with him sometimes?”

“If you get spoken to the way he spoke to me, you’d be cranky, too.”

“Because you knew he was a senior detective, when you spoke to him you knew there was a record of what was said going on?”

“No, I did not,” Savage said. “I knew it in the interrogation room as I call it. But when he was on his phone, I never expected it.”

The trial continues.