Gary Jubelin trial: Mutterings of William Tyrrell’s neighbour

An widower who lived opposite William Tyrrell became a key person of interest after bugs picked up traces of conversations.

An elderly widower who lived opposite William Tyrrell’s foster grandmother became a key person of interest in the boy’s disappearance after bugs in his house picked up traces of conversations that seemed to suggest he may have had a young boy there at some point.

A listening device inside Paul Savage’s home in July 2017 captured him saying something like: “You’re in my place, you do what I want. You’re a little boy, you’re nobody, you’re just a little boy, you don’t tell me, I tell you.”

There was great debate among detectives investigating the disappearance of William, 3, as to what Mr Savage was actually saying, and the bugging took place years after William went missing from his foster grandmother’s house in September 2014.

In another muttered conversation, Mr Savage was heard to say something like: “Make sure you don’t tell anyone, love, they are right after me.”

Some police believed he may have been talking to his dead wife, Heather, about the police investigation into his movements on the day William disappeared.

However, Detective Senior Constable Greg Gallyot, who worked on the intercepts, told Sydney’s Downing Centre Local Court that Mr Savage, 75, who had been so devoted to his dead wife that he wore a photograph of her around his neck for a month after she died, tended to mutter all kind of things to himself.

“He said things along the lines: ‘I did not see it. I don’t remember seeing it. How could I miss it?’ ”

This was thought to refer to a Spider-Man suit police had left on a bush trail for him to stumble upon. Mr Savage insists he reported the Spider-Man suit as soon as he saw it. Detective Gary Jubelin, who headed the strike force investigating William’s disappearance, was of the view that he’d seen it a day earlier, and failed to report it.

“I remember Mr Jubelin bringing it up,” Constable Gallyot said. “In the same conversation, it was: ‘I don’t believe him (when he says he didn’t see it earlier.)’ ”

The constable said the quality of conversations recorded in the house was “poor to very poor”.

The court also heard a recording, allegedly made without a warrant, of Mr Jubelin approaching Mr Savage at his house a few days after Christmas 2018.

They had a brief chat about Christmas, before talk turned to the upcoming inquest.

“As I’ve said, if you do want to talk …” Mr Jubelin said, before Mr Savage interrupted, saying: “I’ve got nothing to talk about.”

Mr Jubelin tells him that the fact that an apprehended violence order had at one point been taken out against him would probably become public during the inquest into William’s disappearance. The AVO was issued after a female postal worker complained that Mr Savage had become obsessed with her, despite her only ever stopping to chat for a few minutes when delivering his mail.

Detective Senior Sergeant Laura Beacroft, who worked on the investigation for two years, told the court that she came to the view in 2018, after exhaustive inquiries, that Mr Savage “was not the person who had abducted, William Tyrrell”.

“There was nothing concrete” to link him to the crime, she said.

Sergeant Beacroft has since left the investigation, but when asked whether Mr Savage was still considered a person of interest, she said: “No. To my knowledge, he’s not an active person of interest.”

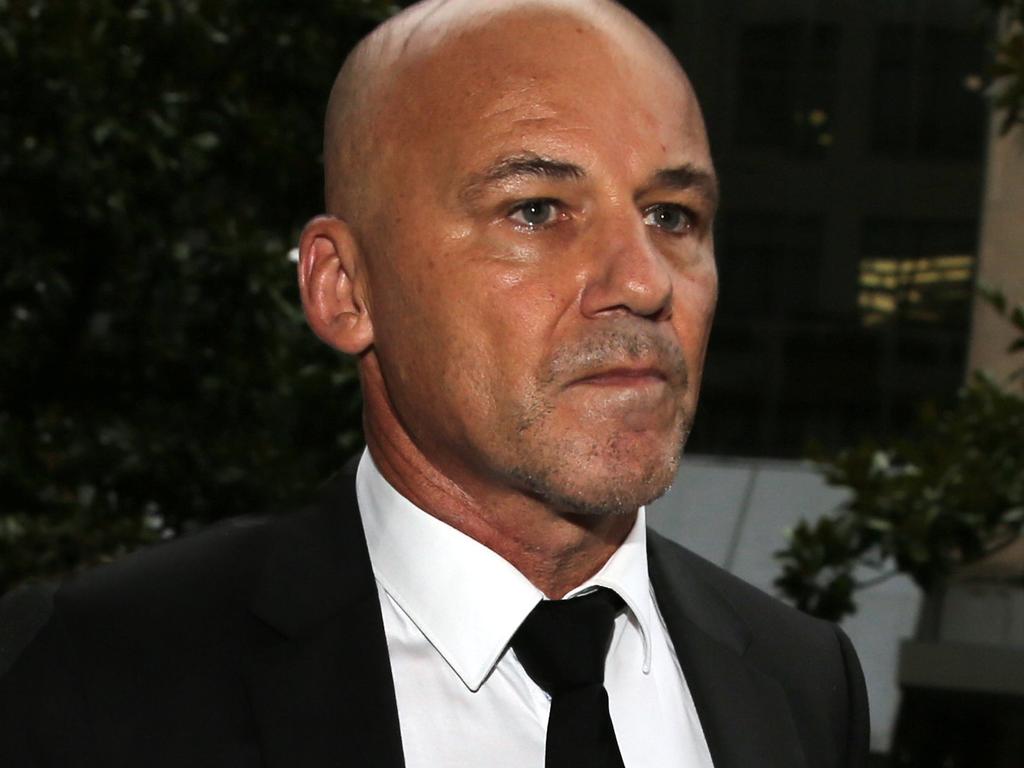

The investigation into Mr Savage has been revealed as part of the trial of Mr Jubelin, a former NSW homicide detective who led the inquiry into William’s disappearance for more than four years.

He is accused of recording conversations with Mr Savage without the proper warrants being in place. The hearing is continuing before magistrate Ross Hudson.