Top income earners carry burden on tax

Spare a thought for the ‘1 per cent’ — they’ve been doing even more of the heavy lifting to replenish Treasury’s coffers.

Spare a thought for the “1 per cent” as they’ve been doing even more of the heavy lifting to replenish Treasury’s coffers.

And until there is tax relief, which could be killed by politics, the burden on those earning above $200,000 a year will keep rising and our tax system will become more complicated and less fair.

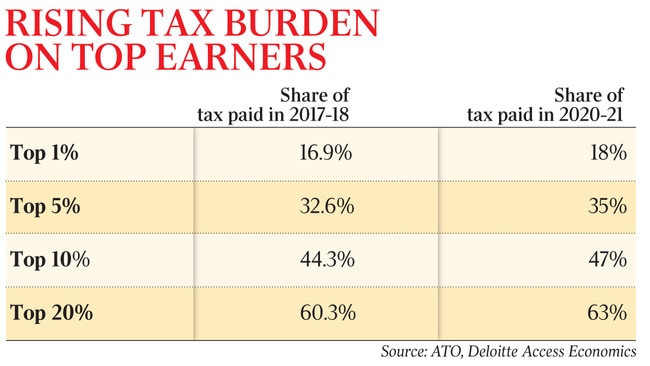

Analysis of Australian Taxation Office data by Deloitte Access Economics partner Chris Richardson shows this year the top 1 per cent of taxpayers will pay 18 per cent of all personal income tax, up from 16.9 per cent three years ago.

The top 5 per cent of earners will contribute 35 per cent of the tax take, while the top 10 per cent will cough up 47 per cent.

The highest-earning 20 per cent of taxpayers will pay 63 per cent of all personal income tax this year, up from 60.3 per cent in 2017-18.

“The notable over-reliance of our tax system on the nation’s highest income-earners continues to become more marked,” Mr Richardson writes in Deloitte’s Budget Monitor.

“Quite correctly, many low-income Australians pay nothing in personal tax. But it isn’t clear that the public realises that this year the top 1 per cent of personal taxpayers will pay the same total dollars in personal tax as the lowest-earning 16.5 million adult Australians.”

A report last week by the OECD revealed Australian workers labour under the third-highest income tax burden in the world, behind only Denmark and Iceland.

Mr Richardson considers the effect on the tax system of the Morrison government’s tax cuts in three stages, announced in April 2019 on the eve of the federal election, and estimated then to be worth $158bn over 10 years.

Josh Frydenberg’s plan sought to simplify the rate scale, kept shares of tax paid as progressive as they were, and addressed bracket creep.

To make the plan more palatable, in stage one, low- and middle-earners were to receive a benefit six years before high earners in stage three, which comes into effect in July 2024.

The first stage was introduced via a complicated device known as the Low and Middle Income Tax Offset (LMITO), to cut out top earners.

But the landscape changed. There was a populist backlash against tax relief for high earners; wage growth collapsed, meaning lower earners benefited even more; and COVID saw stage two brought forward and the first phase was kept on for another year. There is speculation the Treasurer will extend the LMITO, at a cost of $7bn, in next week’s budget.

“The added complexity is thanks to the first stage — designed as a temporary lean-to at the back of the tax system, it would be an unfortunate feature if made permanent,” Mr Richardson says. “And the worsening fairness is because what’s happening is the exact opposite of what Twitter thinks is happening”.

What if stage three, which will cost $17bn in 2024-25 alone, was killed by politics because budget repair was deemed a higher priority?

According to Mr Richardson, the bottom line is that the “worst features of the tax system would stay in place”.

Australia relies much more on personal tax than other developed countries do, because we have a high top-marginal rate of tax, and that top rate cuts in at relatively low levels of income.

He says one saving grace if the current system stays in place is the overall cost of the tax cuts would be lower.

“We at Deloitte have always been worried that they’re too big — that they promised too much too soon. And that was even before COVID-19 hit,” he says.

“To be clear, it’s not the end of the world if that’s where we do end up. At least it would help with budget repair.

“And although it would cement complexity into the tax system and be unfair to high-income earners, it isn’t clear that would make high-income earners work any less than they already do.

“But it is already clear that the politics of budget repair will be tricky.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout